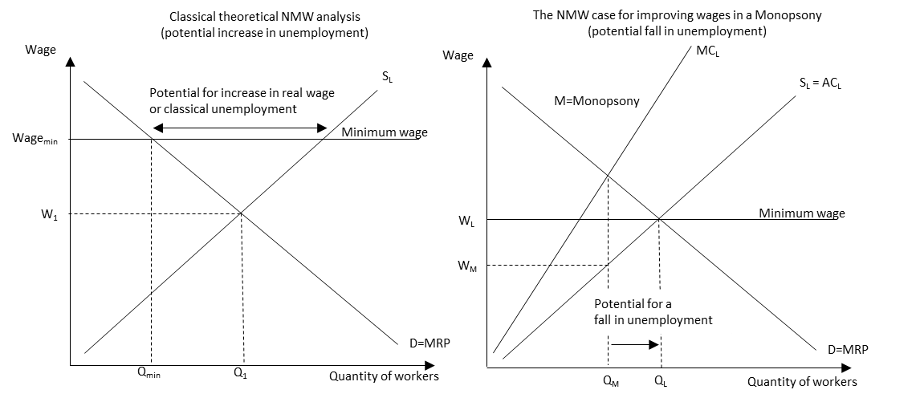

The theoretical premise (Fig.1) for introducing a national minimum wage (NMW) into an economy is embedded in aims to correct market failure, improve income inequality, expand incentives to work, and enhance productivity. That said, this policy can also bring disadvantages such as the potential to increase real wage or classical unemployment as firms recalibrate their requirements for labour in response to rising production costs. The magnitude of precise effects also need to consider the price elasticity of demand of the goods and services that labour produces.

Figure 1: A theoretical framework to analyse the possible effects of introducing a national minimum wage can show both a potential increase and fall in unemployment.

The NMW was introduced in the UK in 1999 (Table 1) as a minimum floor wage rate above the prevailing market equilibrium and today covers some 1.35 million workers.

Table 1: UK National Minimum Wage rates

| Initial rates | Current rates | From 1st April 2023 | % Increase | |

| National Living Wage (23 year old+) | £7.20a | £9.50 | £10.42 | 44.7% |

| 21–22 Year Old rate | £3.60b | £9.18 | £10.18 | 182.8% |

| 18-20 Year Old rate | £3.00b | £6.83 | £7.49 | 149.7% |

| 16-17 Year Old rate | £3.00c | £4.81 | £5.28 | 76.0% |

| Apprentice rate | £2.50d | £4.81 | £5.28 | 52.7% |

| Accommodation Offset | £6.00e | £8.70 | £9.10 | 51.7% |

Year introduced: a2016 b1999 c2004 d2010 e2016

Table 1 can form the basis of a preliminary response to the above question; it is clear that the NMW has increased substantially over the last 23 years (outstripping rises in average earnings and inflation), but has the UK economy benefitted? A review of the main macroeconomic indicators for the UK (Table 2) paints only an inconclusive picture. Other factors will have influenced these metrics like the external shocks of the financial crisis of 2008 and the COVID pandemic, both of which impacted UK aggregate demand and national debt. Nonetheless, the unemployment rate has defied classical projections and fallen from 5.4% to 3.7% with income inequality improving; together these infer that the NMW has not had a detrimental effect on these more closely linked (to NMW) metrics. A more concerning matter is that productivity has remained largely unchanged (trending at 0.4% per year since 2008), which counters arguments that the NMW would improve labour outputs through improved incentives, population happiness and efficiency of wage effects (Fig. 2).

Table 2: Economic performance indicators for the UK

| Macroeconomic objective | 1999 | 2022 | |

| 1 | Sustainable and balanced real GDP growth | £1.56 trillion | £2.23 trillion |

| 2 | Control of Inflation | 1.54% | 10.1% |

| 3 | Lower unemployment rate | 5.4% | 3.7% |

| 4 | Improved productivity | No change in trend see Figure 2. | |

| 5 | Sustainable trade balance in goods and services / current account | £1.3bn (0.1% of GDP) | £44.2bn (7.1% of GDP) |

| 6 | Improved public services / sustainable government finances | National debt was 31.2% of GDP (£486bn) | National debt was 103.7% of GDP (£2,233bn) |

| 7 | Lower wealth and income inequality (Gini coefficient) | 35.1% | 34.4% |

| 8 | Improved national well-being | No change in long run trend of ONS measure of happiness. | |

The data shows that UK productivity has not grown significantly (in recent times) and on average remains between 0 and 2% per annum.

Figure 2: UK productivity (output per hour)

Raising wage rates expand labour supply through both increasing incentives to work and the opportunity cost of work, resulting in individuals choosing to substitute their leisure for paid employment. It then follows that the increased quantity of this factor of production (labour) will improve the productive capacity of the economy and enhance the aggregate supply level within an economy. The current rate of UK unemployment is 3.7%, a value below 5% is often taken as representing full employment and hence it is likely that the increases in the NMW have contributed to this metric.

Turning from a historic perspective to one that looks forward, would further substantial increases in the NMW benefit the UK economy? As significant income inequality still exists there is scope for improvement and further increases should (ceteris paribus) improve this metric. However, rises in the NMW would need to be greater than wage increases for the upper income deciles and fiscal policy, in particular tax band changes, would need to be aligned so to avoid fiscal drag effects which could counter potential improvements in income equality.

Economies grow through investment, so is there a link between NMW increases and investment? In the Keynesian influenced Harrod-Domar model the savings ratio determines the level of investment and changes in NMW will influence the savings ratio. One can assume that increases in NMW lead to increases in disposable income which give consumers the option to save or consume more. If consumers have a greater marginal propensity to save than consume then this will lead to greater investment which in turn will lead to greater national income/economic benefit. Hence, it is conceivable that increases in the NMW could lead to increasing the capital stock of the UK. However, it could be argued (for modern economies like the UK’s) that the link between savings and investment is not very strong and therefore UK policy makers should keep in mind that this scenario is most likely to occur at times of low consumer confidence.

Would alternative policy accelerate or yield greater economic growth? Governments could increase productivity through sustained increases in capital. However the Nobel prize winning Economist, Robert Solow, would have disagreed and argued that capital expenditure only resulted in temporary growth because the ratio of capital to labour will increase. This model implies that growth is derived from labour inputs (which increases in NMW would achieve) and therefore a logical path to economic benefits can be a realistic conclusion. Governments could also introduce supply side approaches such as investment in training and skills or changes to welfare benefits that are designed to improve incentives to work and reduce voluntary unemployment.

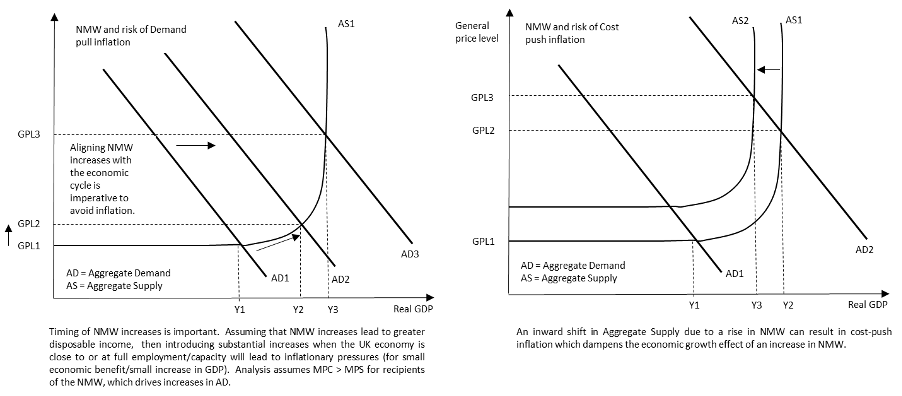

To introduce further sizeable increases to the NMW, timing would be an important factor and policy makers would do well to consider the position of the economy in its economic cycle. Such policy would exhibit beneficial growth if the economy was below full employment, otherwise there is a risk of rising inflation. Therefore, at the current time where the UK is at full employment, increases in NMW will most likely not result in meaningful real economic growth or increases in productivity. That said, the risk of inflationary NMW increases occurring could be mitigated somewhat through well designed and timed supply side policies which would shift aggregate supply outwards allowing for growth and less significant inflation (Fig 3).

Figure 3: A Keynesian analysis of NMW, policy timing and inflation

The theoretical view of both positive and negative effects of introducing a NMW have largely not been evidenced upon analysis of macroeconomic empirical data over the period following its implementation in the UK (the evidence base is still developing). This is because increases in NMW remain muted and should be increased further, for example beyond the current trajectory of 60% of the UK median hourly wage rate to perhaps the greater level of 66%. However, research to date does not highlight any specific detrimental effects to the UK economy and hence there is no reason to withdraw the NMW (which has widely been accepted as a worthy intervention). A logical belief would be that on balance this policy has probably been an enabler for economic growth through decreasing poverty and improving income inequality. Notwithstanding the above, further measures that seek to improve the UK’s productivity (in-order to maximise return to factors of production and growth) are paramount and yet it is also clear that economic benefits (ex-post) are fundamentally related to workers’ preferences, choices and behaviours because labour is an important element of growth theory.