Henry George was a 19th century American economist who founded Georgism, or the movement for a single Land Value Tax. His ideas were immensely influential in his time, with his 1879 book Progress and Poverty selling millions of copies worldwide. But despite this Georgism is rarely discussed today, even though many of the questions he sought to answer are once again resurfacing. Should we tax income or wealth? How can we make housing more affordable? How can we better protect and improve our environment?

Henry George began by focussing on the commons – natural resources such as air and water that are collectively owned by all. He argued that it is inherently illogical for such resources to be privately owned. Air, for example, is naturally occurring, necessary for life and invented by no one – and thus no one has a greater claim to owning air than anyone else. It is ridiculous to say that someone should have to pay to breathe air.

George applied this logic to another natural resource – land – one of the four factors of production. ‘Land’ in this sense refers not only to real estate but to all the resources that come from the Earth: coal, oil, metal ores, timber, crops and so on. Why do we consider it normal for people to own land, when land – like air – is naturally occurring, necessary for life and entirely uninvented? And why do we consider it normal for the owners of land to extract economic rent from those who wish to use that land? In essence, why do we not treat land as something collectively owned by all?

Finally, George addressed what he saw as the paradox of income tax. He argued that society does not have the right to tax the income of other people, as that income was generated solely by them through their labour and hard work. Labour, he thought, is not a part of the commons, and is not a natural resource that should be collectively owned by all.

In Progress and Poverty, George argued that all forms of income tax should therefore be abolished. Instead, society should introduce a single Land Value Tax (LVT), paid by those who own land. Landlords would pay the LVT as a form of dues to society, to compensate the public for its exclusion from their land. Specifically, George thought we should tax the unimproved value of the land, i.e. without considering the value of man-made improvements such as houses or buildings. He argued society only has the right to claim the natural resources of the land, not what is built on it, as the latter is the product of someone else’s labour.

George’s theory was also intertwined with his belief in wealth redistribution and social justice. He argued that, after the government had secured enough revenue to fund its operations, the remainder of the money raised from the LVT should be redistributed equally to all members of society. He called this a citizen’s dividend – a way of ensuring that all citizens could benefit from the land they collectively own. Nowadays this idea, known as Universal Basic Income (UBI) is coming back into fashion, as it is a form of social security that inherently benefits the less wealthy more. This is because the UBI represents a higher proportion of the income of the less well-off compared to the wealthy.

Indeed, one of the main selling points of the single LVT is that it is inherently progressive (i.e. the rich pay more than the poor). Under income tax progressivity has to be artificially engineered, usually by creating tax bands with higher rates for higher earners. But with the LVT only landowners – typically those who are already better-off – have to pay tax. At the same time, workers get to keep the full value of their own labour.

As a result of this, George and many other economists – from Smith to Friedman – have contended that the LVT is a more efficient form of taxation. Income and corporation tax, it is argued, disincentivises working as the relationship between work and reward is distorted. The same goes for indirect taxes such as VAT, which aside from being regressive (affecting the less well-off the most) also discourage consumption and trade.

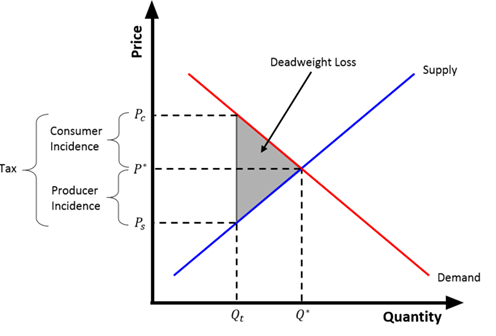

This is because of the economic concept of ‘deadweight loss’. In a free market, consumers aim to maximise consumer surplus – the difference between the highest price they would be willing to pay and the actual price of a product. Producers seek to maximise producer surplus – the difference between the lowest price they would be willing to sell for and the actual price of a product. The supply and demand curves created by these two objectives intersect to form a market equilibrium, where both consumer and producer surplus, and therefore total economic welfare, is maximised.

When direct and indirect taxes are imposed, the tax burden tends to be split between consumers and producers. Consumers have to pay a higher price, while producers receive a lower return. As a result the quantity of goods both demanded and supplied is reduced, with the total loss to economic welfare known as ‘deadweight loss’.

In the graph above, P* represents the market equilibrium price. Taxation increases the consumer price to Pc, while reducing producer profit to Ps. As such quantity supplied falls to Qt. The area of deadweight loss corresponds to the reduction in both consumer and producer surplus. Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Detailed_tax_wedge.png

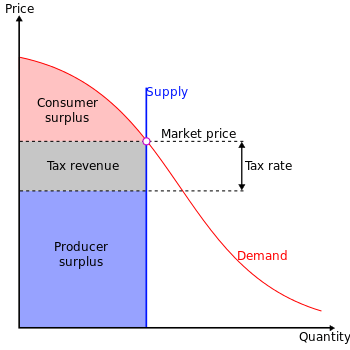

The LVT does not encounter deadweight loss as the supply of land is inherently fixed or inelastic. While it may decrease demand for land, it will not result in a shortage as the supply stays constant. Thus, the productivity of the economy is not reduced.

In the graph above, the tax rate reduces demand, but supply remains constant, resulting in no deadweight loss. Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Perfectly_inelastic_supply.svg

George had a critical view of landlords for what he saw as profiting without contributing value to the economy. He believed the LVT would disincentivise excessive landholding and give a chance for more people to own property. It would also encourage a more efficient and productive use of land – no more could owners simply sit on their real estate, waiting for its value to increase before selling. Since they have to pay tax, they are encouraged to earn income from the land by developing and improving it, perhaps by farming it, or by building houses on it. Since the LVT only factors in the unimproved value of the land, this would not increase a landlord’s tax burden. On the other hand, landlords would be disincentivised from raising rents, as this would mean admitting that their land had gained in value – increasing the landlord’s tax liability. Overall, then, the LVT could result in enhanced productivity, while providing a potential remedy to the chronic housing shortage currently faced in the UK and other countries.

Economists have since discussed the potential environmental benefits of Georgism. Environmental issues such as pollution are often described as externalities, as the damage they cause is not reflected by market prices. However, from George’s point of view polluting the environment is a form of degrading the commons, and thus requires polluters to compensate society. Introducing a pollution tax would therefore be compatible with Georgist teachings.

While no country has ever fully adopted Georgism, Singapore has successfully implemented many of its suggestions. In Singapore the vast majority of land is government-owned, but private individuals are able to obtain leasehold rights for a specific period, usually 99 years. They then pay an annual land rent to the government based on the leasehold’s market value. On top of this people pay a property tax based on the annual value of their land, with the most valuable properties carrying upwards of 20% tax. As a result of these policies Singapore has often been praised for its efficient use of land, low homelessness and high environmental standards.

Georgism was briefly a popular political phenomenon in the later 19th and early 20th centuries, but post-WW2 it has largely been forgotten. Perhaps the most powerful argument against the single LVT is that it severely restricts the amount of revenue a government can raise. Since it focusses the tax burden on landowners, a whole section of society would go completely untaxed. But for many this is Georgism’s greatest strength, not its weakness, and if that means massively reducing government spending, so be it. However, many modern Georgists might pursue a more moderate stance, seeking to use the LVT in conjunction with other taxes, perhaps seeking only to abolish income tax. Whatever your beliefs, Georgism poses a fascinating alternative to our current real estate and taxation systems, two topics which remain hotly debated today.