A modern welfare state typically provides both contributory and means-tested benefits. Contributory benefits are those which depend on individual levels of contribution to a social insurance programme. This is the principle behind Medicare and unemployment insurance in the US, or National Insurance and state pensions in the UK. Means-tested benefits, on the other hand, are only offered to those who meet specific income criteria.

Historically, means-tested benefits have been criticised for their potential to create a ‘welfare trap’ (also known as a ‘benefit trap’, ‘unemployment trap’ or ‘poverty trap’). The concept of homo economicus assumes that all individuals, including recipients of means-tested benefits, seek to maximise the utility available to them in their decision-making. This is defined by their real income and the amount of leisure time they can enjoy. The welfare trap arises when these recipients face a disincentive to enter low-paid work, or to work longer hours, as any rise in income will be offset by the withdrawal of means-tested benefits, a rise in income tax, an increase in work-related and childcare costs, and a fall in non-working hours.

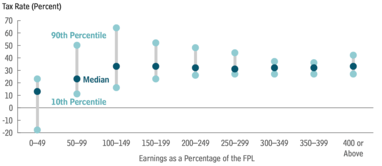

An economy’s Effective Marginal Tax Rate (EMTR) is the primary indicator of the presence and severity of a welfare trap. The EMTR shows the percentage of an extra unit of income which is lost due to tax and the removal of means-tested benefits. If a rise in pay at low-income levels faces a high EMTR, there will be a large disincentive for benefit recipients to seek employment. This is especially true if the EMTR does not rise smoothly as income increases, but instead goes up in sudden ‘cliffs’. Usually this occurs because means-tested benefits are not removed gradually as pay increases, but are withdrawn in lump stages after certain income thresholds are surpassed. This is problematic as it disincentivises individuals from seeking to earn above these specific thresholds.

A case study can be made of the two most expensive means-tested benefits in the US; Medicaid and the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP). Eligibility for both these benefits is tied to the Federal Poverty Line (FPL), which currently stands at $15,060 for a one-person household. Generally, an individual will no longer qualify for SNAP benefits once their income rises above 130% of the FPL, and will lose access to Medicaid if they earn above 138% of the FPL. In 2016 the US Congressional Budget Office estimated that, due to these income thresholds, the median EMTR faced by low-income individuals rose from 14% to 34% as pay increased from 50% to 150% of the FPL.

A similar problem is faced by the UK’s primary means-tested benefit, Universal Credit (UC). Introduced from 2013 onwards to replace six legacy benefits systems, UC attempts to avoid sharp ‘cliffs’ in the EMTR by allowing households with children to earn a ‘work allowance’ before their benefits are cut. This currently stands at £631 per month, or £379 per month if the household gets help with housing costs. Above this sum a 55% taper rate applies, meaning that every pound earned above the work allowance will correspond to a 55p reduction in the recipients’ UC award.

While this means that under UC households will always earn more with a job, an individual on the National Living Wage (which currently stands at £10.42) would only leave their family better off by £4.69 per hour worked. Factoring in work-related costs such as commuting, work clothes and lunches, coupled with increased expenditure on childcare, could mean that a UC recipient faces negative utility from entering paid work. This is worsened by the fact that the work allowance is granted per household, not per individual, meaning that a family with more than one earner will not enjoy a larger work allowance. A 2021 commission on “supporting progression out of low pay” led by Baroness Ruby McGregor-Smith for the Department of Work and Pensions, concluded that UC “can act as a disincentive” as increases in income “can be very small and workers do not believe that there is sufficient reward for taking on greater hours and undoing stable and trusted childcare and transport arrangements”.

Child Benefit is another form of welfare that has been criticised for creating income disincentives in the UK. Child benefit can be claimed by one parent/guardian per child, if their yearly pre-tax income is below £50,000. For every £100 earned above this threshold the claimant has to pay a ‘Child Benefit tax charge’ equal to 1% of their Child Benefit award. This means that Child Benefits will be completely rescinded once the recipient reaches an income of £60,000. The result is an anomalously high EMTR between the income levels £50,000 and £60,000. A parent receiving Child Benefit for three children would experience a 65% EMTR for every pound earned in this bracket; higher than the marginal tax rate for every pound earned in the highest tax band, which applies to incomes above £125,000.

In his 1962 book Capitalism and Freedom, the famous free market and monetarist economist Milton Friedman presented the conditions which he believed had to be met in order to create an efficient welfare system. First, Friedman argued that any welfare programme should alleviate poverty “in the form most useful to the individual, namely, cash”. Thus, he opposed all forms of in-kind benefits such as food stamps or nationalised healthcare; as he saw it, a robust system of monetary assistance would allow these services to be provided by the free market, which would maximise competition and maintain the consumer sovereignty of the recipient. Second, Friedman opposed what he called a “seemingly endless profusion” of different benefit programmes. By creating a singular, universal programme of monetary assistance, government waste could be reduced by cutting down on administrative costs (which, indeed, was part of the reason behind the introduction of Universal Credit by the UK’s Coalition Government in the 2010s). Finally, Friedman asserts that an efficient welfare programme cannot “distort the market or impede its functioning” through measures such as “price supports, minimum-wage laws, tariffs and the like”, or create the possibility of a welfare trap.

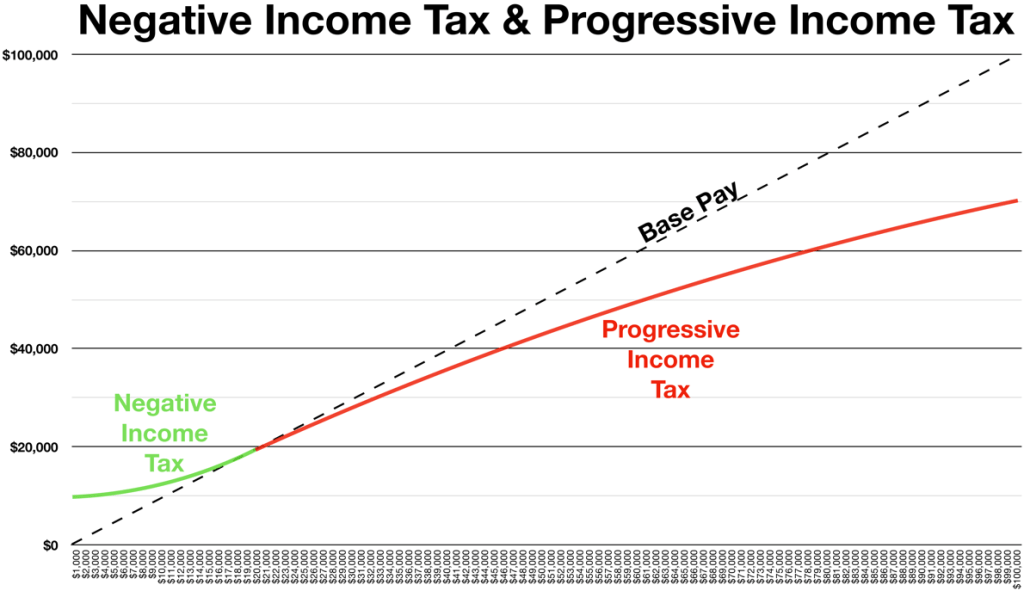

Friedman concludes that “The arrangement that recommends itself on purely mechanical grounds is a negative income tax”. Under a Negative Income Tax (NIT) system the government would set a basic income threshold. This threshold would be subtracted from an individual’s earnings to determine their total taxable income. For example, if the threshold were set at $20,000, someone earning $100,000 would have a positive taxable income of +$80,000; an individual earning $20,000 would have a break-even taxable income of $0; while a person earning $10,000 would have a negative taxable income of –$10,000.

The government would then impose a rate of tax on each person’s taxable income. For instance, if the government sets a positive tax rate of 20%, the individual with +$80,000 in taxable income would pay +$16,000. In all likelihood, positive taxable incomes would be subject to progressive taxation just as they are now, with higher tax bands applying to higher incomes. However, the government would also set a negative tax rate for those whose incomes fall below the basic threshold. For example, if this rate were set at –50% a person with –$10,000 in taxable income would actually receive a subsidy worth $5000.

Source: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/9/9f/Negative_Income_Tax.png

The negative income tax would therefore result in a guaranteed income floor, or ‘universal basic income’ (UBI), provided to those who have no income whatsoever. In this example someone earning $0 would have a negative taxable income of –$20,000, entitling them to a subsidy worth $10,000.

The crucial point of NIT, which differentiates it from other UBI proposals, is that the value of the subsidy is always a proportion of someone’s negative taxable income, rather than its full value. If the state committed to supplement the full difference between the basic threshold and a recipient’s income, the benefits system would have a 100% EMTR; every dollar earned would correspond to a dollar of welfare withdrawn. Under NIT, however, any increase in pay below the basic threshold will result in a proportionally smaller reduction in the subsidy. This results in a negative EMTR at income levels below the basic threshold; i.e. for each additional dollar earned, a recipient’s total income will increase by more than one dollar due to the subsidy.

While Friedman makes clear that such a system still “reduces the incentives of those helped to help themselves”, it does not “eliminate that incentive entirely”, thus preventing a welfare trap. It would also fulfil Friedman’s other conditions; it provides benefits in-cash rather than in-kind, “It operates outside the market”, and “could be substituted for the host of special measures now in effect”. Indeed, Friedman posits that such a system would significantly increase administrative efficiency as “The system would fit directly into our current income tax system and could be administered along with it”.

Despite Friedman’s critical tone towards welfare in general, there is no reason why NIT cannot be far more generous than current forms of means-tested benefits. The key variable would be where the basic threshold is set, and hence where the guaranteed income floor would fall. By choosing to set an appropriately high threshold, it would be entirely possible to maintain and even improve existing standards of wealth redistribution under an NIT framework.

Friedman’s idea for an NIT enjoyed a brief period of popularity in the mid-20thcentury. President Nixon famously attempted to introduce a nationwide NIT scheme under his 1969 Family Assistance Plan, but the bill failed to pass into law after encountering opposition from both right and left in Congress. Instead, between 1968 and 1980 the US government sponsored four NIT experiments in New Jersey, Rural Iowa and Carolina, Indiana, and Seattle-Denver, while the Canadian government sponsored one in Manitoba.

While all these experiments demonstrated that the NIT lowered the incentive to work compared to having no welfare system at all, there was little evidence of workers permanently withdrawing from the labour market, as occurs during a welfare trap. This suggests that, as intended, the NIT does not create an outright disincentive to work in the same way traditional benefit systems might do. The results in the US also suggested that an income floor of between 50% to 150% of the FPL would have been financially comparable to existing welfare spending at the time. Thus, while NIT began to fade into obscurity from the 1990s onwards, there is perhaps good cause for economists to re-evaluate its feasibility.