Labour refers to all productive forms of human output, mental or physical. As one of the four factors of production, the quantity and quality of labour is a key determinate of an economy’s productive potential. On the surface, this might seem to justify policies aimed at increasing wages and maximising the incentives to work. However, such policies can ironically reduce the availability of labour, due to the unique behaviour of the labour supply curve.

In the social sciences assumptions must be made to simplify human behaviour. Here it is assumed that individuals have a mutually exclusive binary choice of how to spend their time: between work or leisure. Given that work and leisure exist in a binary, they come at the opportunity cost of the other, i.e. more work results in less leisure time and inversely, more leisure time results in less work.

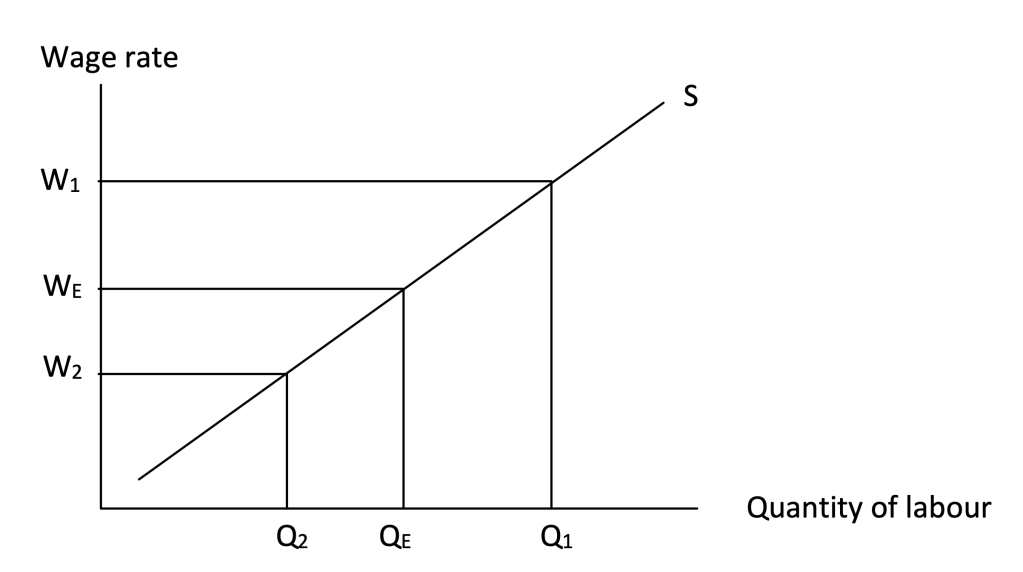

It is crucial to distinguish between the labour supply curve for the market and the labour supply curve of the individual. The labour supply curve of the market is shown above. Diagrammatically, the increase in the wage rate from WE to W1 brings about an extension in supply from QE to Q1 and oppositely, a fall in wages from WE to W2 brings a contraction in labour supply from QE to Q2. This implies that increasing the wage rate increases the quantity of labour; it assumed there exists another worker who is willing and able to offer labour at any given price level.

However, in reality, the relationship between wage rate and hours worked, on an individual level, is not so linear; workers also value their leisure time, which comes at a great opportunity cost the more hours they work.

The shape of the individual labour supply curve is determined by two effects: the income effect, and the substitution effect. The positive income effect states that as wages rise, the hours offered for work by the individual increase, as the individual rationally aims to maximise income. Consider the individual labour supply curve above. Starting at a low number of hours worked (between Q1 and Q2), the worker has plenty of leisure time – meaning the opportunity cost of an hour worked is low, as defined by the substitution effect. So when wage rates rise, the worker readily substitutes leisure time for work time – and gets a positive change in their income that outweighs the loss of leisure time.

As more hours are worked, the opportunity cost of leisure time rises as the remaining hours in a day become more scarce. The worker desires a higher wage rate to compensate for this opportunity cost. As hours worked tends to Q3 the value of lost leisure is not compensated for by increased income. The individual offers less hours as the wage rises, the income effect starts to become outweighed by the substitution effect labour supply curve steepens quickly at this stage.

Eventually, individual labour supply curve bends backwards (between Q3 and Q4) due to the fact that many individuals have a target income in mind. With a higher wage rate, they can work less hours and still achieve the target income. The worker no longer responds to higher hourly wages by offering more work, instead they accept the wage increase and work less. Here the income effect is outweighed by the substitution effect, and the curve bends backward (as shown above)

In 2013, Adib J. Rahman of Mount Allison University conducted ‘An econometric analysis of the “backward-bending” labour supply of Canadian women’. An extract from his paper reads:

“…wage has a significant positive effect on hours of work until a turning point of negative $10.9/hour is reached, and beyond this value wage has a negative impact on hours of work. This means that hours of work increase with wage at a decreasing rate and this relation gives a backward-bending supply of labour for Canadian women.”

However, it should be noted that the backward bending labour supply curve is quite subjective, the magnitude of the income and substitution effects vary from individual to individual as the study confirms.

“The substitution effect is greater among with who live alone – compared to women who live with partner earning wage”

“Young women are more likely to have stronger substitution effect and respond to higher wages by supplying more labour”

The concept of the backward bending labour supply curve is important for a myriad of reasons. Primarily it provides an insider perspective to the labour supply curve for the market which could be thought of as consisting of an array of individual labour supply curves; given that each worker’s responsiveness to changes in hourly rate varies, so does the shape of their curve. This works out such that at any wage rate, there exists a worker who is willing to supply labour (higher wages may even attract new entrants to the occupation) and because of this, the labour supply curve for the market is strictly linear. With this, employers, acting in their best interest, must be aware of this curve to avoid overpaying employees and not receiving the extra labour through hours worked and policymakers should acknowledge how this affects tax brackets, tax rates and benefit rates.