Productivity is defined as the amount of output produced per unit of input. The most commonly used notion is labour productivity which denotes output per working hour. It has been widely acknowledged that the UK has suffered from a productivity problem: a 0.3% decrease in GDP per hour compared to 2022 and a decrease of 24% from the forecasted trend pre-financial crisis, ranking the UK bottom of all developed economies in Europe. This issue has become more adverse for the economy and households alike due to the dependence of real wages on labour productivity. In this article, three factors accounting for the UK’s productivity problem are considered: total factor productivity (henceforth TFP), capital intensity, and human capital.

The Solow-Swan endogenous growth model is used to analyse these factors which hinder UK productivity. As can be seen in (1), an increase in Capital (Kt), TFP (At) or Labour (Lt) – thus collectively leading to an increase in augmented human capital (AtLt) – will increase total output, thereby increasing productivity with the assumption that input remains constant. In the following sections, this article will expound on the problems the country faces in these aspects, with some targeted solutions provided respectively.

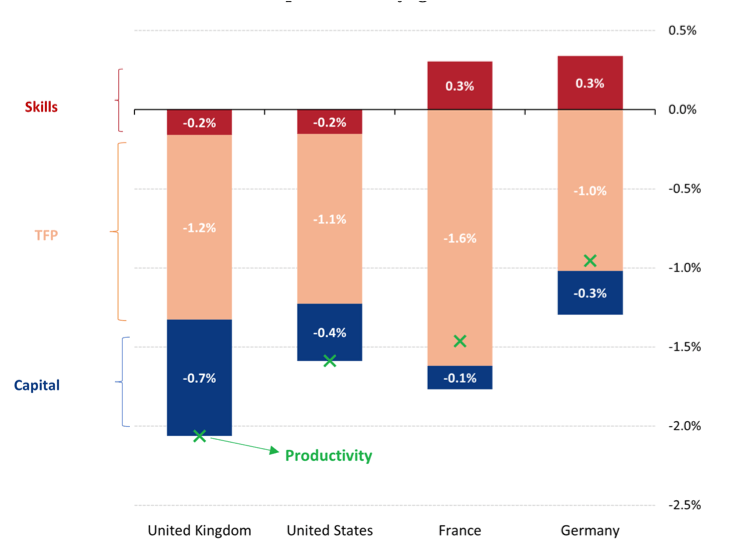

TFP as a residual term denotes the portion of output unexplained by the amount of input. This measure of productivity has suffered major declines in the economy: TFP in 2023 has only risen by 1.7 per cent above the recorded levels in 2007 and at a fraction of the pace. One of the major causes of low TFP is underinvestment which lowers a company’s budget for Research and Development (henceforth R&D), hindering the opportunity for technology breakthroughs and thus causing a slower rise in productivity. This chronic underinvestment problem poses an additional threat to capital intensity, which arguably accounts for a greater problem than TFP when compared to other developed economies. For example, Figure 1 shows that France has the greatest TFP decrease at -1.6% which is 0.4% higher than the -1.2% of the UK. Despite this, the UK has experienced the greatest overall decrease in labour productivity. Nevertheless, TFP must not be neglected.

Figure 1: Productivity Decrease Post-financial Crisis

By addressing these issues, the UK can foster an investment-friendly environment, thereby attracting domestic investors and Foreign Direct Investments (henceforth FDI). This can be achieved through government-led investments in ‘sunrise’ industries such as artificial intelligence and green technology. Selective long-term infrastructure investments help create the structural foundation for sustained innovations, including for example the computational capacity necessary for AI advancements. Fiscal subsidies can be issued to help with R&D and promote commercialisation, thus uplifting the technological level of the economy. Corporate tax abatement can also be used as part of the subsidy scheme to further create incentives for the development of these industries.

However, it is necessary to acknowledge that this might impose a budget constraint on a government which is already suffering a long-term debt problem. Further borrowing will aggravate the debt crisis. In addition, industrial policies can distort free market forces which will be fiercely opposed by various stakeholders. Thus, we must design a set of policies to create a broad coalition of interests to minimise friction.

Apart from the lack of profitable investment opportunities, domestic political instability and changing priorities have further dampened the incentive to invest as investors from home and abroad are put off by increased political risk and policy uncertainty. For example, tariffs and customs checks introduced by Brexit turned away many EU trading partners, causing a scarcity of goods, and thus driving up prices. In turn, investors raised concerns about the prospect of certain industries and were discouraged from further investment. This, along with the pandemic, decreased investment by 20% in 2020. Furthermore, the Truss-Kwarteng “Mini Budget” dropped the pound to $1.03 on 26th September, lowering the values of FDIs and causing an outflow of investments, exacerbating productivity dip due to persistent underinvestment.

In tackling political uncertainty, the government can go further along the path of power delegation, establishing an independent National Growth Council suggested by the LSE Growth Commission to allow professional and experienced economists to deliberate and draft policies untainted by narrow partisan interests. This, in turn, prevents political manipulation such as purposeful fiscal expansions before electoral cycles. This prevents policy discontinuities following government turnovers, increases confidence in sound economic decision-making, and builds trust with FDIs. This will allow long-term investment partnerships to benefit the economy in the long run.

Apart from flat TFP and underinvestment, another problem that the UK faces is sluggish and uneven growth of human capital caused in large part by disparate concentration of skilled/graduate workers. A high concentration of them congregates in high-productivity and high-wage regions, notably the ‘Golden Triangle’, consisting of London, Cambridge, and Oxford. The flight of human capital to these places means a lower supply of skilled workers in less productive and poorer regions of the UK and forces firms to use low-skilled workers to exercise high-skill tasks. This compels them into a Low Equilibrium Trap: a state of low productivity which disincentivises the demand for skilled workers and Further Education programs to improve the workforce. As a result, productivity inequality is aggravated further. Hence, for UK productivity to see growth, human capital must be cultivated across the whole country; expanding productivity in the Golden Triangle is not enough.

Regarding the improvement of low-skilled regions, the government can devolve power to local authorities for them to create educational programs which are specifically tailored to their needs. Thus, money can be used more effectively to target especially weak regions and not misspent in already skilled areas. To see a quick boost in skill improvement and productivity, authorities of relatively low-skill regions can adopt skill development programs for AI such as the use of ChatGPT to uplift the average productivity of low-skilled workers in less developed regions and help them out of the Low Equilibrium Trap.

In conclusion, it is acknowledged that the government has a finite monetary budget. Thus, it is not feasible to implement all the strategies aforementioned simultaneously. Given the deepening credit crunch and persistent government debt, supply-side policies should be preferred over expansionary monetary or fiscal policies to improve productivity without igniting other problems.