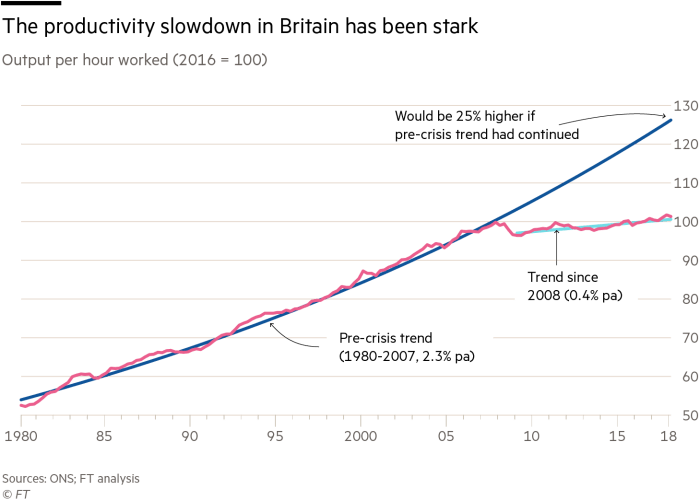

Amidst the complexities of the UK economy, productivity stands in the way of sustained economic growth. The UK’s productivity has barely grown since the financial crisis. One method of measuring this is through using total factor productivity (TFP). Since 2007, just before the financial crash the following year, the TFP of the UK has only increased 1.7%, compared to the 27% increase from the 16 years preceding 2007. If productivity had continued to grow at pre-2007 levels, our TFP would be 20% higher than it is currently.

But why does this matter, and what are the best solutions to this problem?

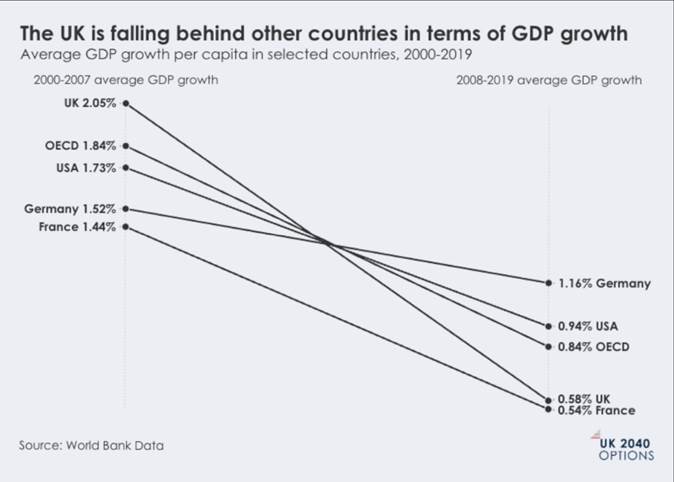

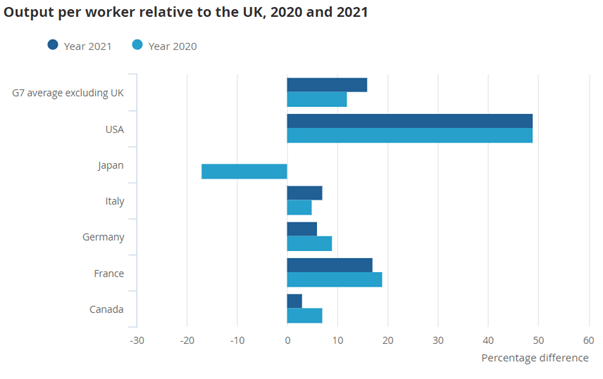

Firstly, the TFP measures how efficiently resources are used in the economy through comparing total output and total input, rather than the number of resources in the economy. Theoretically, there could be more resources in the economy, yet the TFP could decrease, as they are being used less efficiently. However, this very rarely happens, as TFP is often considered the primary contributor to GDP growth. This is why the TFP of an economy is important. If you have to same amount of input, but you are able to increase productivity, then you will grow the economy. If this stagnates, or even decreases, then a country’s economy is going to struggle to grow, such as what has happened in the UK over the past 16 years. As the following charts show, the UK’s economic growth and its TFP have stagnated compared to other developed countries.

There is clearly a problem with economic growth in the UK, which has been correlated to minimal growth of TFP in the economy. However, increasing TFP is not a simple fix. There are multiple different methods, each with varying degrees of effectiveness.

One way of increasing productivity in the UK economy is through investing in productive industries. The UK economy is supported by a huge financial sector, which also happens to be one of the UK’s largest. Investing in this highly profitable sector through government policies that incentivize foreign investment can stimulate foreign competition and boost GDP. This approach also shifts the Long-Run Aggregate Supply (LRAS) curve outward. As a result, increased innovation leads to improved factors of production and productive capacity due to better and more advanced technology, which can further expand the Production Possibility Frontier (PPF) of the economy and is coupled well with sustainable, low term economic growth thanks to an increase in the allocative efficiency of the sector. Coupled with investment in productive sectors is reducing the influence of unproductive ones. The productive sectors drive innovation, but the unproductive ones simply use up resources – such as labour, capital and technology – that could be better and more productivity used through being reallocated to more productive sectors, increasing overall TFP.

One of the drawbacks of this solution is that relying on presently productive sectors is economically riskier than other possible solutions. This solution inherently decreases the diversity of the economy, meaning it is more vulnerable to external shocks and policy risks. This is where a second possible solution arises; increase public investment. Poor public investment has led to a lack of money going into infrastructure, education and skills, and healthcare. Investing in education especially will allow more productive human capital, developing critical thinking for future workers, with possible solutions for more efficiency, as well as inspiring creativity. It has been shown that investment in human capital, in developed countries, exerts a significantly positive effect on TFP of around 10%. This is arguably a safer, and much easier solution to the productivity paradox, given it is easy to simply reallocate spending, and is much less likely to be affected by external economic shocks. Further, we can reallocate members of society to underemployed sectors that have potential to become productive, large sectors of the UK economy.

Another reason that detracts from simply hoping for external investment into a sector is because the cause of the productivity puzzle has still yet to be identified. In fact, some believe that the productive, innovative sectors, once thought to be increasing the UK’s TFP, are actually bringing it down. This could be explained by the slowdown in innovation since 2008, meaning that though productivity is still increasing, it is doing so at a much slower rate, leading to a decrease in TFP. Further, it is true that not every firm in a sector has the same productivity, and there are indeed huge gaps in productivity within sectors. This leads onto a different possible solution. We need to invest in these unproductive ones, creating financial incentives for increases in human capital and technology will allow unproductive companies to ‘catch up’ to the more productive ones.

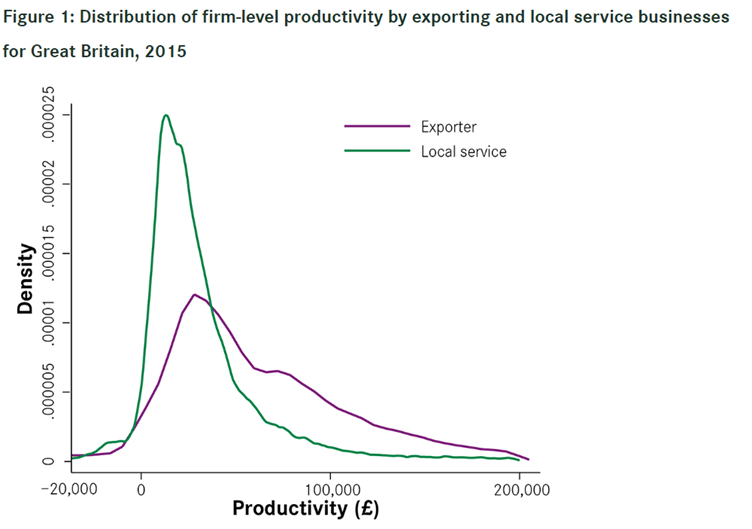

A last solution to increase productivity is through the investment of export companies. Local businesses make up a huge majority of the low productivity companies. However, we can’t expect a hairdresser or a restaurant to significantly improve their efficiency. Therefore, we have to rely on export companies (companies that export things to foreign markets), such as manufacturing or ICT, to drive the UK’s TFP. As shown in the following graph, local services are concentrated in their productivity, whereas exporters are more evenly distributed.

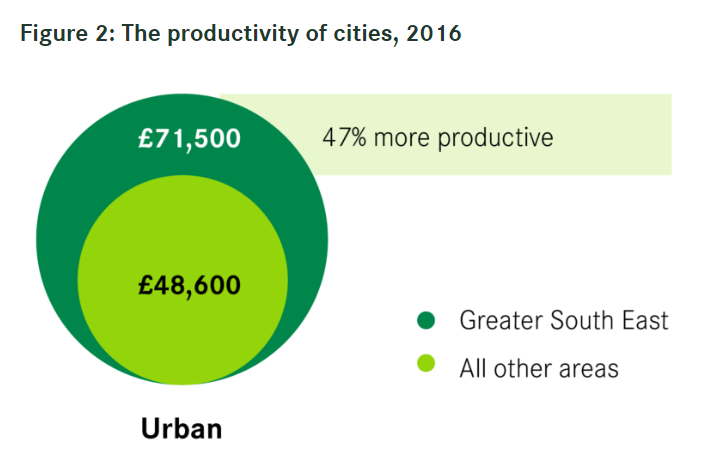

On average, the Greater South East has more productive exporting firms than the rest of the UK. Most exporter companies are located in cities, yet, due to either undesirable city centres, or a lack of skilled workers in these cities, high-performing exporting companies are not investing in these less productive cities. To improve TFP, we must incentivise investment into the less productive cities and reduce our reliance on the GSE for productivity growth. This can be achieved through improving the skilled workforce through education, making companies more attracted to these cities.

I believe that the most productive method of increasing the UK’s productivity the most efficiently is through investment into education and a diversification of export firms away from the GSE area. Education provides more human capital, which can increase our TFP, but also make us more attractive for investment through more innovation and technological advances and breakthroughs. Further, diversification of export firms – the driving force of increases in TFP, will allow us to hugely increase the UK’s TFP, as well as improving the livelihoods of millions through higher, more competitive wages.