“Growth for the sake of growth is the ideology of the cancer cell” – Edward Abbey, The Second Rape of the West, 1975.

In the above quote, Abbey refers to the shrinking wilderness of his beloved Arizona, industrialised by resource extraction and urban expansion. However, such a statement goes far beyond wilderness: when economic expansion is the common goal, it damages the very foundations that sustain it, risking inequality, environmental collapse, and diminishing returns.

Elias Canetti described humanity’s ‘will to grow’ as being an instinctual drive – a set belief that expansion equals security and success. This was quantified back in 1934, when Simon Kuznets developed the modern concept of GDP, a method to track such ‘growth’ on a national level. Since then, governments have used this measure of economic performance as a ‘North Star’ of policymaking. Across the world, governments hail rising GDP as a success, and so tend to campaign on promises to increase national GDP. Yet, even Kuznets himself reminded society that ‘the welfare of a nation can… scarcely be inferred from a measurement of national income’ in his original report to Congress. Ultimately, what if our obsession with growth is the problem, rather than the solution?

Growth as a problem:

- Fundamentally, growth depletes our environment. Global resource use has tripled since 1970, and we are now using up to 1.75 times what the Earth can regenerate in a year. Throughout the 20th century, society’s blind pursuit of growth, without considering ramifications, has shattered the world’s foundations. Climate change (Figure 1 below), water and air pollution, and diminishing biodiversity are several of the countless crises that weren’t acknowledged until the last few decades. We are now at a stage where every 1% of global GDP growth corresponds to over 10 billion tonnes of CO2 emissions, forming the problem that is discussed in every single annual COP (Conference of the Parties) meeting: can sustainability be achieved in a world that chases growth?

Figure 1:

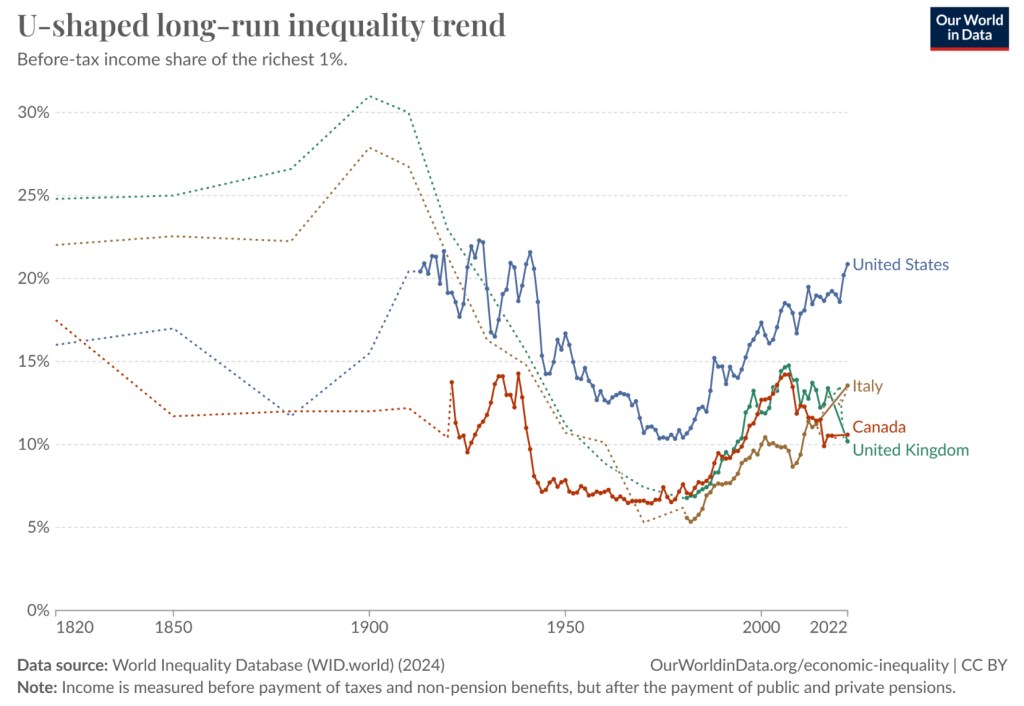

- In today’s era, growth causes inequality. Figure 2 (below) represents inequality as a share of pre-tax income held by the richest 1%. It indicates a recovery (decrease) after the Second World War, along with a consistent increase since the 1970s. The US has now reached inequality levels that have not been met for roughly a century, whilst similarly influential countries have followed the same trend over the last 50 years – a time of rapid GDP growth and technological innovation. Economic growth is so correlated to inequality that Professor Richard A. Falk calls growth a ‘subsidy for the rich’, which accentuates the increasing wealth gap that comes with expansion. This raises yet another imminent question of whether the classical ‘growth model’ truly serves the majority.

Figure 2:

The Doughnut Model:

Kate Raworth (Oxford economist) developed a ‘compass’ for modern governments to pursue, in her book Doughnut Economics, 2017.

Figure 3:

Rather than endless growth, the goal here is balance. The inner circle represents humanity’s basic needs; the ‘ecological ceiling’ pictures overconsumption on an unsustainable level. Raworth envisions a stable society, functioning in the light green – a ‘regenerative and distributive economy’. Yet, in recent decades, we have been clearly pushing outwards, with unsustainable growth that moulds an imbalance in society’s ‘doughnut’.

Example of a Strong Doughnut Economy:

Figure 4:

Denmark is a role model for all economies to follow. Figure 4 shows that whilst the country’s population has been gradually increasing, emissions per capita have dropped. This proves that their policies allow for the growing population to contribute effectively to environmental sustainability.

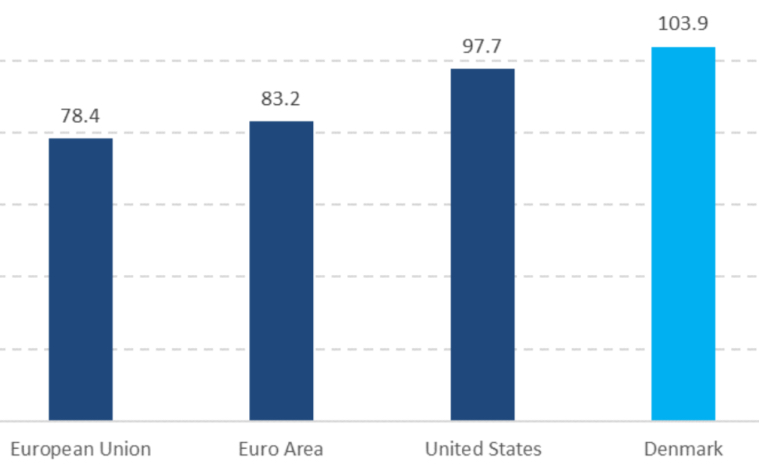

Figure 5: GDP Per Hour Worked, 2023

Comparing Denmark with countries like the US, Figure 5 displays how the country capitalises on utilising their growing population. Citizens are working for less hours, yet producing higher output than most economies. Additionally, Denmark’s poverty rate is at 5.5% – the second lowest globally – compared to the US’s 17.8%, despite America generally being considered as ‘second to none’ (by Joe Biden). Yet, these measures clearly show just how much better some countries are than the typical US economy, a country defined by high GDP growth and technological innovation. However exciting the concepts of growth and innovation may seem to children, voting citizens should understand that it is not a priority in the face of uncontrollable global emissions and inequality.

What’s Next?

A post-growth economy (where the government prioritises living standards, inequality, and sustainability over economic growth) does not correlate with decline; it means redefining success. Instead of chasing higher GDP numbers, we have to focus on balanced outcomes. The following is a list of existing measures that can be combined to indicate a country’s real progress:

- Genuine Progress Indicator (GPI): In 1995, Clifford Cobb, Ted Halstead, and Jonathan Rowe developed GPI as a metric to define a nation’s welfare by the fusion of social, environmental and human conditions. It is calculated by the sum of: Personal consumption (with income distribution adjustments), capital growth, welfare contributions, defensive private spending, social capital (the potential to benefit from social connections), natural capital (e.g. air, water, or soil), and environmental costs.

- Human Development Index (HDI): This is calculated by coupling the three basic human development aspects: health, education, and living standards. The HDI is a general summary of how well a country is allowing their citizens to develop as people.

- Ecological Footprint Accounting: There are several ways to calculate this measure. In general, it is a reliable, collective system to determine the environmental impact of the country.

Countless economists have set out to reinvent economic goals of governments and citizens by creating such measures. However, these alternative metrics remain largely absent from society. Unlike GDP – a widely reported figure that is ingrained in policymaking – indicators which account for sustainability, inequality, and well-being are overlooked. Even finding data on counties that have successfully balanced these factors is surprisingly difficult. If our aim is to control growth with said ‘other’ factors, economies must educate their population on balanced metrics, using ideas like the ‘doughnut model’ to influence policymaking and education. A final thought – if we measure success by sustainability and well-being instead of GDP, how many of these ‘booming’ economies would be in crisis?