The 2017 Grenfell Tower Fire, which claimed 72 lives, served as a wake-up call to the inequalities in rich countries. Inequality, which is the variance in levels of wealth within a population, is globally measured using the Lorenz Curve.

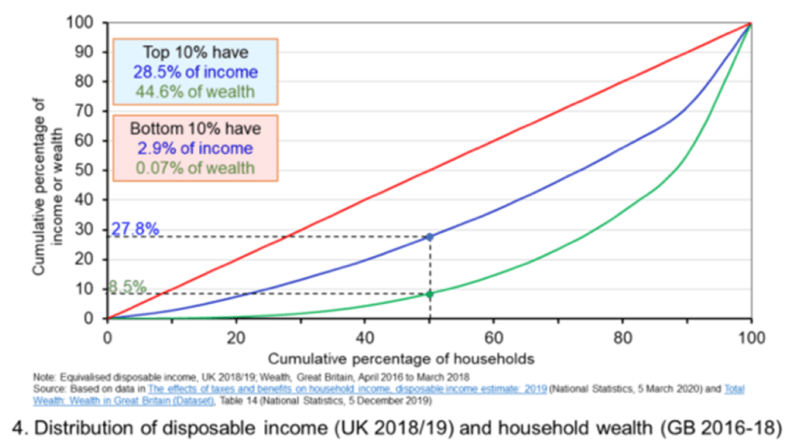

Figure 1: Lorenz curve for the UK (2018/19)

In figure 1, the 45 degree line (red) represents perfect equality, and the more a Lorenz curve sags below this line, the higher the level of inequality; for the UK, the poorest 50% of society only has 8.5% of total wealth. To address the stark inequalities that prevail, an understanding of their root causes is critical.

Arguably, the paramount cause for this disparity is education. Education in the UK – compared to other developed countries – is highly segregated, in that children from lower income families attend lower quality schools and receive poorer educational outcomes. This substantial attainment gap between institutions in the UK can be clearly seen through a disparity in public exam results; in 2021, 70% of independent school pupils were awarded the top grades of A and A* for A-Levels, in comparison to 39% for those at state schools. Consequently, this translates into a large disparity in wages and earning potential.

In the UK, there is also a vast divergence in wages between the public and private sector. Individuals in the private financial sector and technologically-savvy industries earn substantially more than those in public sector occupations such as doctors in the NHS.

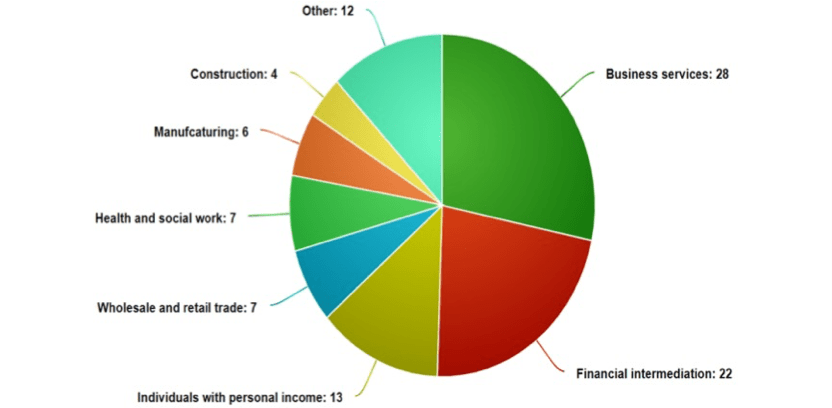

Figure 2: Breakdown of individuals with income over £150,000 by sector (%)

Figure 2 shows that 50% of individuals in the UK with income over £150,000 belong to the financial and business sector.

Moreover, another relatively important factor of income inequality in the UK is unemployment. In recent years, this issue has been exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic, which made 1.3 million people unemployed from its beginning to December 2022. Inevitably, the largest impacts were felt by the poorest members of society due to their limited ability to work from home.

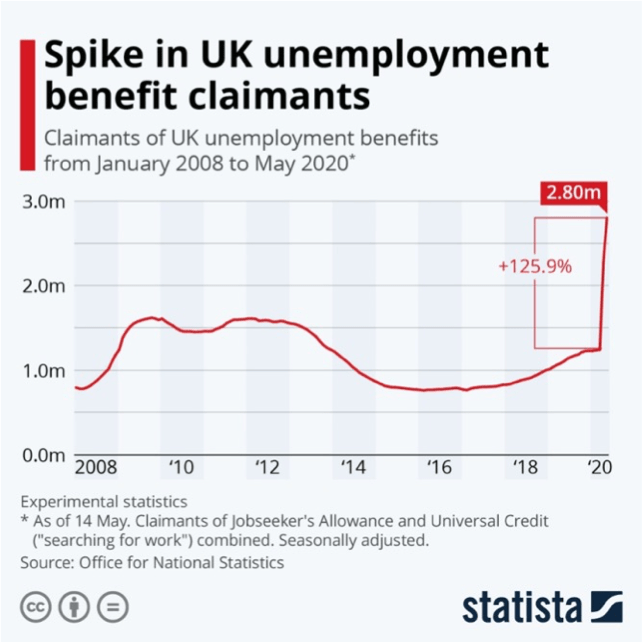

Figure 3: Number of people on state benefits in the UK

As seen in figure 3, the number of people on state benefits in the UK radically increased in 2020, hence showing that the issue of income and wealth inequality is growing.

Furthermore, in the UK, a large proportion of the population is composed of pensioners who are reliant on state welfare benefits by the government; a study run by ONS in 2021 showed that 18.6% of the total population were aged 65 years or older. These people cannot increase their income above what the government facilitates them with as they have retired, exposing them to an increasing amount of vulnerability and fiscal instability. According to a comprehensive review of national data by the Guardian, in 2022, one in five pensioners – more than 2 million people – were living in relative poverty (they receive at least 50% less than the average household income) in the UK.

In addition, globalisation has also been blamed for the rising inequality in the UK. The benefits of globalisation have undoubtedly gone to the rich and educated, whilst the low-skilled poor workers cannot access those benefits. For example, outsourcing and cheap low-skill imports, have reduced wages and increased unemployment for the poorer individuals, whilst specialisation in high-skilled occupations has increased the gap between skilled and unskilled workers. To quote Richard Freedman, a professor of economics at Harvard University, ‘the triumph of globalisation has decreased living standards for billions while concentrating billions among the few’.

Undoubtedly, there are a plethora of strategies that the government could employ to tackle inequality in the UK. The most significant method is introducing even more stringent progressive taxation. Introducing even higher tax rates for those earning higher incomes would not only directly decrease the gap, but would also allow for the government to use the additional revenue to fund social programs that benefit low-income families. For example, the government could allocate the funds to improving educational opportunities for such families, enhancing healthcare services, or even providing job training programs and employment support services for low-income individuals.

Another strategy could be to increase the minimum wage in the UK; as of the 1st of April 2023, the national living wage in the UK stands at a paltry £10.42 per hour for those over the age of 23. Increasing the minimum wage would not only help lift some workers out of poverty, but would also result in lower benefits being given by the government – as people can now support themselves financially. This is important as the government could now prioritise giving more to the unemployed, who are not currently able to improve their income or wealth.

A third approach could be to improve investment in education. This would help improve the job prospects of those from low-income backgrounds and so decrease the incessant discrepancy between those born into poor and rich households. Additionally, another potential scheme is social safety nets (such as welfare programs) or incorporating elements of socialism, notably handing over social services to the government, which would make them free at the point of use. Further strengthening of these would ensure that those struggling financially have access to the help they require. Furthermore, whilst the predominant onus may be on individuals, the government must encourage each citizen to take broader ownership of their work and promote the culture of entrepreneurship. In 2011, UK based employee-owned companies had a turnover of over £30 billion (2 percent of GDP) and employed over 130,000 people! Undoubtedly, part of the success of these companies is linked to the employees having an increased motivation and engagement due to having a direct stake in the company’s success through ownership.

To conclude, these are the main causes of income and wealth inequality in the UK, coupled with the key strategies that the government could employ in order to tackle this rising issue. In my opinion, the largest factor is the disparity in education, due to the fact that it directly links to the high unemployment, poverty rates, and the huge disparity between high and low-skilled jobs. However, this issue would be mitigated by improving government investment in education, and other measures such as increasing the national minimum wage and encouraging citizens to take broader ownership of their work can also be useful.