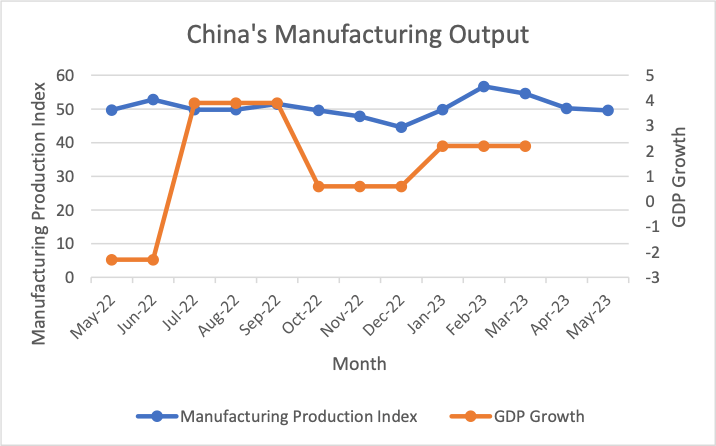

June’s Chart of the Month highlights the stagnation in China’s manufacturing output after the pandemic.

When China unexpectedly reopened at the beginning of 2023, many analysts expected an immense recovery. However, their forecasts have been disproven, particularly regarding China’s manufacturing activity, which has fallen after a slight increase (an index score below 50 indicates a contraction). This is not because of a stunted reopening, but a reflection of the underlying factors which have plagued China for years.

Many economists have attributed this decline to weak demand; geopolitical tension between China and the United States has led to trade tariffs on Chinese exports rising to an eye-watering 19.3%. Since annual bilateral trade between these two nations totals $730 billion, making it the largest trade relationship in the world, this would have had a significant impact on overall demand for Chinese goods. Weak consumer demand in China’s typical trading partners, such as Russia and Hong Kong, which have been plagued with slow economic growth, has exacerbated this impact.

More importantly, foreign firms within China have chosen to relocate to other Asian countries, particularly Vietnam, Malaysia, and Bangladesh. Indeed, a survey conducted by Gartner revealed that a third of corporations in China before the pandemic, including Apple and Samsung, will move operations by the end of this year.

One reason this happened is because manifold companies were forced to manufacture elsewhere during China’s almost three-year long lockdown, and did not have the resources to move back when the nation reopened. Closure of pivotal ports, such as those in Shanghai and Ningbo, and disruption to the movement of raw materials posed especially great challenges to this effect.

In addition, rising wages in China have contributed to this dearth of manufacturing activity. Improved regional infrastructure and specialisation have increased worker bargaining power to the point where average salaries rose by 9.7% from 2020 to 2021. When the average wage in Vietnam is slightly over half of that in China, the former becomes a more attractive region for investment.

Finally, a crackdown on firms by the Chinese Communist Party, both domestic and foreign, have heightened hesitancy to invest in China as executives reconsider the safety of their assets and employees. Not only were such concerns buttressed by the witch-hunt for Jack Ma, the founder of the technology giant Alibaba, but also surprise raids on Bain and Mintz Group earlier this year.

This decline in manufacturing may be worsened by the imminent shortage in semiconductors, which may make it harder for firms to develop their productive capacity, particularly if firms wish to automate. China will have to contend with America’s imposition of the Foreign Direct Product Rule, which effectively bans it from accessing any semiconductors made with US parts, and this has been followed by similar restrictions from Japan and the Netherlands. It is also reported that South Korean producers Hynix and Samsung have been lobbied by the American government to not make up for the shortfall that this will create in the Chinese chip supply.

The blow to China’s manufacturing industry will be vast, as shown by the corresponding slow GDP growth for the last financial year; the sector employs 18% of the country’s workforce and represented 38% of its total output in 2020. Along with China’s troubled property market and high youth unemployment, this decline may play an instrumental part in severely crippling the world’s second largest economy.