In the final quarter of 2021, India overtook the UK and became one of the world’s top 5 largest economics (amongst powerhouses such as the US, China, Japan, and Germany). Now the country is projected to be the 3rd largest economy by 2027 ($5.4 trillion GDP by 2025) and has the largest population, overtaking China in April 2023. It is interesting to witness how a former British colony has risen to such prominence.

In July 1991, the nation started a series of liberalisation and globalisation reforms (decreased taxation on imports and exports, privatisation, policies to lower the cost of production for firms) that opened its markets to foreign commerce and investment. A growing middle class, urbanisation and remarkable economic growth ($321 billion GDP in 1990 to $3.6 trillion in 2023) have all been spurred by this policy change. India has advanced technologically as well, emerging as a major global hub for software and IT services. However, the country continues to face difficulties such as income disparity, environmental issues and complicated geopolitical relations with neighbours China and Pakistan (ongoing border conflicts with Pakistan in the Kashmir region and with China in the Himalayan region). With shifting political dynamics and an increasing focus on digital governance, India’s dynamic democracy has continued to change. The COVID-19 pandemic presented particular difficulties, exposing the country’s healthcare system’s problems (e.g. increasing healthcare costs having heavy burdens on the poor). India’s path in the twenty-first century is still under international notice as it manages these issues.

When European powers first stepped foot on Indian soil in the late 15th century, a complicated and revolutionary chapter in Indian history was launched. A notable historical event was the Jallianwala Bagh massacre of 1919 where over a thousand peaceful protesters were killed by the British. The British East India Company’s entry at the beginning of the 17th century signalled the start of a strong colonial presence. India became a focus of European imperialism throughout the following centuries as Britain eventually took control of major portions of the subcontinent. During this time, India’s riches were exploited, western institutions were adopted, and British influence expanded its reach to many aspects of Indian culture. According to Oxfam, the income inequality can be traced back to the colonial age, “affecting access to basic services, education, and healthcare, and impeding the realisation of economic and social rights.”

Mahatma Gandhi, Jawaharlal Nehru (the first Prime Minister of India) and others spearheaded the fight for independence with mottos of non-violence and peaceful protesting, resulting in India’s liberation from British rule in 1947. Nehru’s policy in the late 1940s and early 50s was to ‘modernise’ India and to not let religious taboos interfere with development: “No country or people who are slaves to dogma and dogmatic mentality can progress, and unhappily our country and people have become extraordinarily dogmatic and little-minded.” – Jawaharlal Nehru: A Biography Volume 1.

Since the fall of the empire, India has undergone radical change with liberalisation, privatisation and increased investment to foster economic growth. It is clear that Nehru’s policy succeeded when comparing the Indian economy recently to the pre-independence era – around $500 GNI per capita in the 1940s to $6,500 in 2015 (in PPP). Another statistic that illustrates the extent of Indian economic development is its rise in GDP from $37.8 billion in the 1960s to $3.17 trillion in 2021. However, there are still problems with income disparity as the richest 1% of India’s population control 58% of its wealth. The graph below shows this growth categorised in pre-colonial and post-colonial ages.

By Filpro – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=49187835

This success can be attributed to several key factors, notably its demographic dividend. India’s sheer population size and youth offer substantial advantages for economic growth and sector shift. Industrialised countries such as the US and UK have higher working populations (18-64) than younger people. Japan has more pensioners and is in a population decline. The potential for productivity, creativity, and entrepreneurship is extensive when there is a sizable working population. As these young people enter the workforce, they contribute to an increase in the labour supply, which fuels economic growth. Additionally, this demographic dividend can enable the country to fulfil the demands of the global market, draw in foreign investment, and accelerate technical breakthroughs if it is adequately harnessed through education and skill development. But in order to fully utilise this advantage, India could make investments in high-quality jobs, healthcare, and education (all while reducing a prevalent problem of corruption). This could enable the nation’s rapidly growing youth population to realize its full potential and guide the economy of the nation toward long-term prosperity.

The chart below illustrates the youthful nature of India’s population.

Another remarkable reason India has seen such triumph is through its development in IT and technology sectors (sole leading provider of IT services globally). The country has developed into a powerhouse for information technology and software services on the planet ($108 billion in IT/technology service exports in 2022) due to its commitment to education and trained labour force. The outsourcing boom is defined by Indian IT companies (such as Infosys, Wipro, Tata providing software development services) providing high-quality, reasonably priced services that have traditionally been done domestically to clients abroad. It has not only produced millions of jobs but also significant foreign exchange revenues. India’s IT proficiency has not only increased its GDP (7.5% of the country’s GDP in the fiscal year of 2023) but also helped to enhance infrastructure and develop skills, making it a significant factor in the nation’s quest for long-term economic growth in the 21st century.

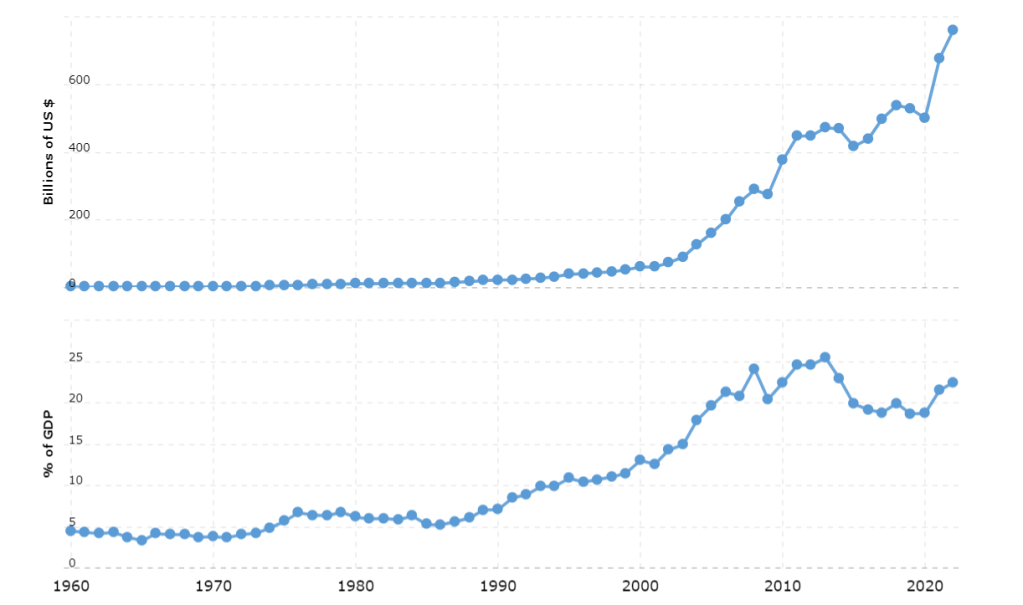

The Indian economy has also been greatly assisted by trade and manufacturing (making up 17.4% of its GDP in the fiscal year of 2020). It has enabled India to develop its export-oriented industries, such as IT, pharmaceuticals, and textiles by developing global economic ties and opening up access to worldwide markets. Increased output, the creation of jobs, and gains in foreign exchange have resulted from this. The chart below illustrates the total sum of exports India has produced from 1960-2023 and how much of its GDP it makes up. It is seen that exports nearly make up a quarter of India’s current GDP, reinforcing the reasons for investment in export-oriented sectors.

India’s involvement in international trade agreements has increased its significance in the global supply chain. It continues to be an essential engine of growth, diversification, and global connectivity for the Indian economy – even while difficulties like trade imbalances still exist (-$27.98 billion as of September 2022). Policies that could reduce this deficit are increased taxation and lower government spending.

India has discovered its potential to emerge as one of the foremost economies with the greatest rate of expansion attributed to its sizeable population, dynamic workforce, and various economic sectors. The rise of the IT sector, youthful population spread and trade expansion are all factors that have served as significant drivers of this growth. However, the way forward necessitates continuous support for structural changes, expenditures in healthcare and education, and the promotion of favourable business and innovation-friendly environments. India’s economic path speaks volumes of the country’s tenacity and potential. As it develops and reforms, it continues to be a compelling case study in the world economy.

Good going Shreyas!

LikeLiked by 1 person