The Transition away from fossil fuels is one of the key economic driving forces of this decade. A key way for countries to wean themselves off hydrocarbons is through the replacement of internal combustion engines with electric battery powered engines. Electric Vehicles (including plug in hybrids) have seen a surge in production over the last few years. China is at the forefront of this global trend, as the world’s leading producer of EV’s at 65% of global market share.

China has been in a trade war since January 2018 when the Trump administration began setting tariffs on Chinese goods coming into the US, 7.5%-25% tariffs on $370 billion worth of Chinese imports (Source; Reuters). This was mainly done to reduce US Intellectual property theft from Chinese competitors as well as boost US jobs in manufacturing. Since then, the trade war has been persistent with the US trying to slow the offshoring of its own firms to China for cheaper labour costs. This is a clear representation of a movement away from globalisation as now due to intense geopolitical rivalry there has been a larger push for onshoring, most notably in the US.

A key example of this US push for onshoring was the Biden administration’s Inflation Reduction Act (2022). Out of $891bn of authorised government spending, $783bn was directed towards renewable energy and climate industries (Source; Congressional Budget Office) in the form of subsidies. This represents a large push from the Federal Government to try to counteract Chinese subsidies to firms therefore reducing China’s dominance in industries such as EV production.

China dominates the current EV market for a few distinct reasons. Most notably, as of March 2024, China produces 80% of the worlds Lithium-ion batteries. China has also increased its control of mining for essential rare earth minerals such as Cobalt and Manganese (also essential for battery production) not only within its borders but also overseas in countries such as the DRC (producing 70% of global Cobalt) where 15 out of 19 mines in operation are either owned or partially owned by Chinese firms (Source; CSIS). This has allowed China to operate a strong supply chain for their battery sectors linking to their strong production of EV’s.

Furthermore, according to the CSIS subsidies by the CCP to the EV sector cumulatively total $230.9 billion since 2009. This has allowed Chinese EV manufacturers to sell their EV’s at far more competitive prices than those made in the US. The average EV cost in China is $34,400, while in the US the average stands over 60% higher at $55,242 (Source; World Economic Forum). Linked with these subsidies are China’s very competitive labour costs (for both skilled and unskilled jobs). Average yearly wages in manufacturing have been increasing rapidly in China since 2012 however they are still far below the US. The yearly average wage in manufacturing (China); $14,601 (US); $63,024. (Source; Bureau of National Statistics). China’s combination of strong state sponsorship of industry, competitive labour costs and secure access to raw materials have enabled its champion auto manufacturers.

China’s booming domestic demand for EV’s has also created a strong momentum for continued growth in this sector. China has consistently invested into infrastructure supporting the increased production of EV’s amounting to a 56-gigawatt capacity across the country, in the form of 1 million charging stations (Source; ICCT). This has made EV’s a more practical vehicle for the population; rather than combustion engines. In addition, the CCP has authoritarian power to impose significant policies in order to meet their renewable energy goals and this is precisely what has been done with the EV industry. Key policies include having EV’s make up 45% of new car sales by 2027 and ending the production of internal combustion engine vehicles by 2025 (Source; The Guardian).

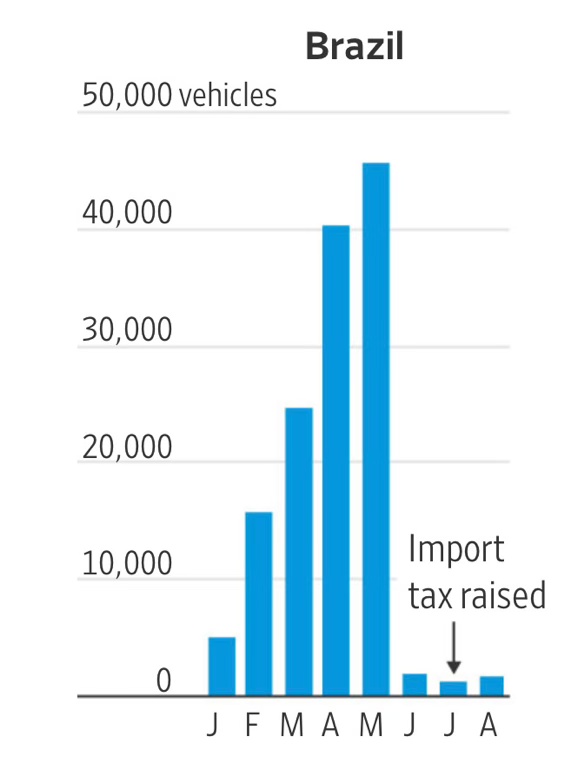

Countries have been increasing their imports of EV’s from China, however when tariffs are introduced to slow these imports very clear effects can be seen. For example, in Brazil where an 18% tariff was introduced on EV imports (moving to 35% in 2026), imports dropped significantly (See graph above, Source; WSJ). The sudden drop in demand indicates that demand for imported Chinese EV’s is highly elastic, in this case. The use of tariffs have been weaponised in particular by the US (100% tariff) and EU (35%), (Source; European Commission), who want to decrease the price competitiveness of Chinese EV’s being sold in their markets. These subsequent tariffs, an example of the West’s intense protectionist policies, will not necessarily hold strong for the future as Chinese production sites have gradually started to emerge particularly in Eastern European nations.

In conclusion, China’s intention to continue increasing their EV production is clear. The tariffs imposed by the EU, in particular, will become less impactful as Chinese manufacturers such as BYD have started constructing and operating their own plants and manufacturing sites in Europe to mitigate these tariffs.