It is certainly true that UK productivity has hardly grown in the years since the Financial Crisis. It is also the case that the UK has performed worse than other developed economies. However, the reason for this relative under-performance does not lie with “total factor productivity” (the portion of outputs not explained by the amount of inputs used in production). In considering what strategies are best for improving UK productivity, it’s best to consider what caused the UK’s slump in productivity. The word ‘productivity’ can be used in different ways. In this essay, I will use the word to mean ‘Labour Productivity’ which is a measure that compares economic output against the amount of labour required to produce that output.

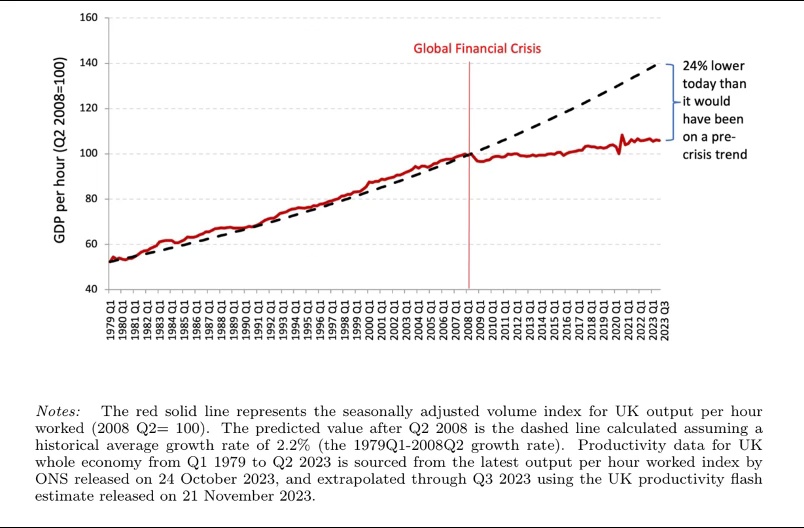

In an LSE academic paper entitled ‘Cracking the productivity code: An International Comparison of UK Productivity’ (November 2023), John Van Reenen and Xuyi Yang explain the lack of UK productivity growth. They commented that “the UK has experienced a dramatic slowdown in labour productivity growth since the global financial crisis”, as depicted in the following exhibit, taken from their paper.

Exhibit I

Total Factor Productivity” (TFP) is one input into the measure of overall labour productivity. As cited in the essay question, it is only “1.7% above the level recorded in 2007”. This lack of growth in TFP is relevant in explaining why productivity in the UK and other countries has grown so weakly in recent years; but it is not the only cause, and it is not unique to the UK. Exhibit II, also taken from Van Reenen and Yang, compares productivity in the twelve years before and after the Financial Crisis in the UK, USA, France and Germany. All four countries have lower productivity growth and lower TFP growth. In fact, TFP growth in the UK was 0.4% higher than in France, despite France’s total productivity growth being higher. This would suggest that there are other factors, such as slow capital and skills growth, which have determined the UK’s lack of productivity growth. Strategies are more likely to succeed if they focus on UK specific problems, so we need to understand what those are.

Exhibit II

Exhibit II shows that the UK’s capital growth (the increase in assets of investment in an economy) at -0.7% is the lowest out of all the countries analysed, and its skills of the labour force worse than in France and Germany. This analysis suggests that a lack of investment in the UK compared to other developed countries is the main cause of the UK’s poor productivity growth, with lower skills growth also being relevant. The paper’s abstract sums up this view: “Britain experienced a much larger slowdown in the growth of capital intensity than other countries, and it is this (alongside a smaller contribution from slow skills growth) which accounts for the particularly severe ‘productivity puzzle’.”

So how can business investment and skills be improved in the UK? In an article written in July 2023, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) suggests several ways in which this can be achieved.

Its first point was that the UK should create “a permanent set of tax incentives that could potentially apply to investments – increasing investor confidence.” One example of this could be the UK government lowering corporation tax on companies who make higher capital investments. By making conditions more favourable for investment, this should encourage companies to invest more. However, as the Institute of Public Policy Research explains in its September 2022 blog “Cutting corporation tax is not a magic bullet for increasing investment”; corporation tax needs to be precisely targeted to avoid being ineffective and wasteful. It argues that investment is more likely to be encouraged by long-term policy consistency, mission-driven approaches (eg aiming for Net Zero) and broad government involvement beyond the Treasury. Van Reenan and Yang also argue for tax reforms, but not for a lowering of corporation tax – “there remains a bias towards debt instead of equity financing of business investment. And we also need a radical overhaul of the way property is taxed, moving to a land value tax, and away from stamp duty, council tax, and business rates.”

The IMF also believes in “liberalising the planning system – reducing barriers to investment in new industries and facilitating the mobility of both firms and workers.” One example of this could be the UK government making it easier for those companies looking to invest in infrastructure to acquire planning permission. At the moment the planning system is hard to navigate as each council has its own separate local planning authority. The UK government could centralise the planning system to make it easier for businesses to invest in infrastructure and other productive projects. The LSE paper cited earlier supports this point – “it has been long recognised that the planning system is not fit for purpose. It holds back development in some of our highest productivity clusters and industries, such as life sciences in the London-Cambridge-Oxford ‘golden triangle’.”

Finally, the IMF also addresses the skills issue: “an expansion of good quality apprenticeships and career counselling in schools to tackle high employment among young people. (…) upscaling, and knowledge, development, and higher investment in the education and training of young adults, can strengthen human capital and raise labour productivity.” One example of this could be the UK government increasing public spending on education. In 2022-23, total public spending in the UK on education was £116 billion. This represents an 8% fall from 2010-11 spending. Van Reenen and Yang also support the view that higher education reform is needed – “higher education is a strong export industry in Britain (Costa et al.,2023). But intermediate skills are weak for those who do not go to university. Reform of the system of further education, vocational and adult skills and apprenticeships could both raise skill levels and reduce inequality (Layard, McNally and Ventura, 2023).”

In conclusion, to improve productivity, the Chancellor should focus on strategies that encourage capital investment and improve skills. These may include reducing corporation tax, modifying the planning system, and increasing investment in higher education. In my opinion, these are strategies that will allow the UK to most effectively close the productivity gap with other developed countries.