During the 19th century, the UK stood as the preeminent global superpower. From the British Raj in India to the Dominion of Canada, its riches and power were unmatched. Since the height of the empire in 1922, when the UK governed 23% of the world population (458 million people with a domestic population of only 42 million) (Source: Statista), the UK has seen a gradual decline in the dominance it once commanded. This is the result of a combination of economic, political, social, and international factors. This article will delve mostly into the economic shifts compounded by the effects of both World Wars, the UK loss of global influence, the rise of new global powers and more recently Brexit.

The roots for the UK economic decline date back to the end of WWI that disrupted global trade dominated by the UK and severely strained its economy resulting in massive debt, inflation, and a weakened industrial base. Net debt as a percentage of GDP reached a historic high of 187.5% in 1922 which was followed by an increase to 251.8% in 1946 (Source: Institute for Fiscal Studies). Following WWI, the global shift towards mass production, which especially benefitted the US, contributed to accelerating the UK’s relative economic decline that was especially hit hard by the global economic downturn of the 1930s contributing to high unemployment, deflation, and further weakening of its economy.

At the end of WWII, the UK was heavily in debt with its industrial base also being damaged. The financial and administrative costs of maintaining the British Empire became unsustainable, accelerating the wave of decolonization across Africa, Asia, and the Caribbean. This shift, while partly motivated by economic pressures, also reflected growing global opposition to colonial rule and a push for self-determination, further reducing the UK’s global power and influence. This culminated in the Suez Crisis in 1956 with the failure of the UK and France to maintain control over the Suez Canal in Egypt that marked the end of the UK’s status as a global superpower and highlighted its diminished military and diplomatic influence.

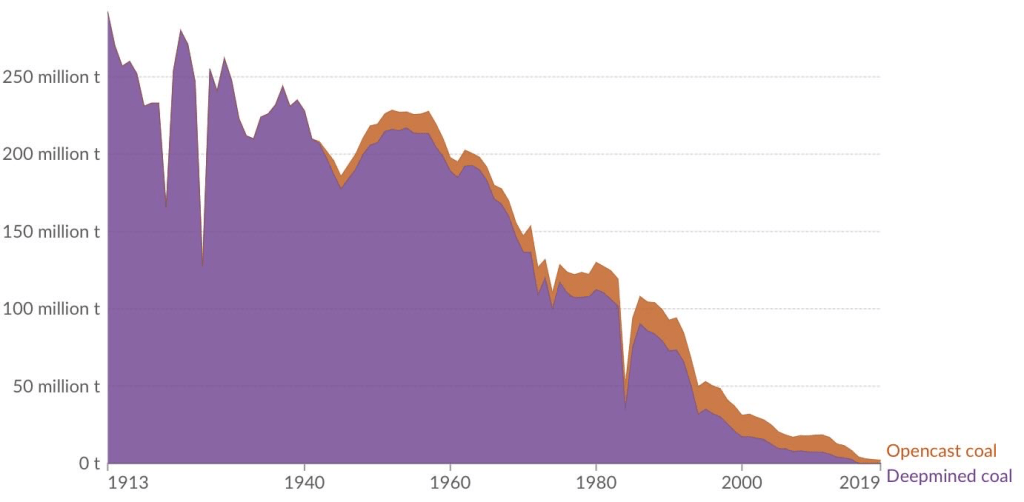

During the post WWII period, the UK experienced slow industrial growth, labour strikes, and an inefficient economy. The welfare state, created in the 1940s, added a significant financial burden. High taxation and government spending, while providing benefits, also led to increase national debt and reduced incentives for business. The shift towards an increasingly service-based economy combined with inadequate management of key industries, led to the decline of British manufacturing with industries such as coal, steel, and textiles, which had been once the pillars of the UK economy, losing competitiveness. See graph below for changes in coal production in the UK (Source: Our World in Data).

UK Coal Production 1913-2019 (Opencast/Deepmined)

By the 1960s, the decline of the UK’s manufacturing industries accelerated due to increasingly uncompetitive labour costs leading to Britain’s deindustrialisation, stagnation and tepid manufacturing growth of only 1.3% between 1973 and 1992, compared to the US’s 55.2% during the same period. This marked one of many instance in the UK’s post-imperial economic landscape where it began to consistently lag behind its foreign rivals.

While the UK benefited from globalization, it also faced stiff competition from emerging economies, particularly in Asia. The rise of China and India, as well as the shift towards a more interconnected global economy, made it harder for the UK to retain its competitive edge. Chronic underinvestment in modernising and expanding its manufacturing infrastructure, combined with an intense offshoring by firms, meant that UK manufacturers found it progressively harder to compete in the global market.

The 1970’s saw a series of strikes and industrial unrest that disrupted the UK economy. Unions wielded significant power and conflicts between labour and management hindered economic recovery. A silver lining consisted of joining the EEC (now the European Union) in 1973, which gave the UK access to a larger trade market, enabling businesses to expand exports, attract foreign investment, and benefit from tariff-free access across member states. This contributed significantly to revive the nation’s economic growth in subsequent decades. In 2016, the decision to leave the EU led to significant political and economic uncertainty, damaging the UK’s global standing.

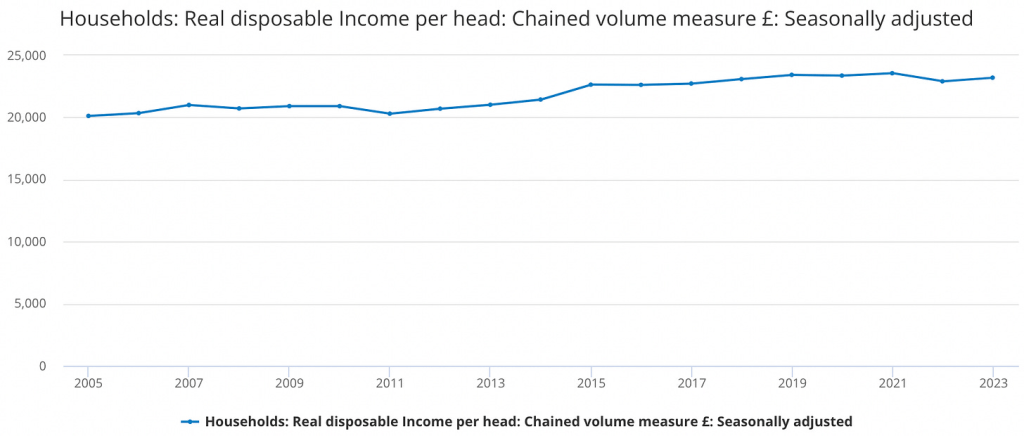

It is no secret that the UK is currently under extreme socioeconomic pressure. Three back-to-back economic shockwaves—Brexit, COVID-19 pandemic, Ukraine War—have left the UK saddled with unsustainable debt levels. Net debt as a percentage of GDP has increased from 36.3% in 2007 to 98.1% in 2024 (Source: Office for National Statistics). The initial catalyst dates back to the Financial Crisis of 2008 when the UK government borrowed an extra £137 billion to bail out British banks (Source: House of Commons Library) and opted for austerity measures to focus on managing public finances and debt. While austerity reduced deficits, it also curtailed public investment, contributing to stagnant growth and declining productivity over the following decade. The UK’s fiscal policy did not include tangible minimum wage increases or inflation control policies leading to a flatline effect on households’ real disposable incomes. See chart below (Source: ONS). Real disposable income only increased by £3,017 compared with the US, where it increased by $12,745 over the same time frame (Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis).

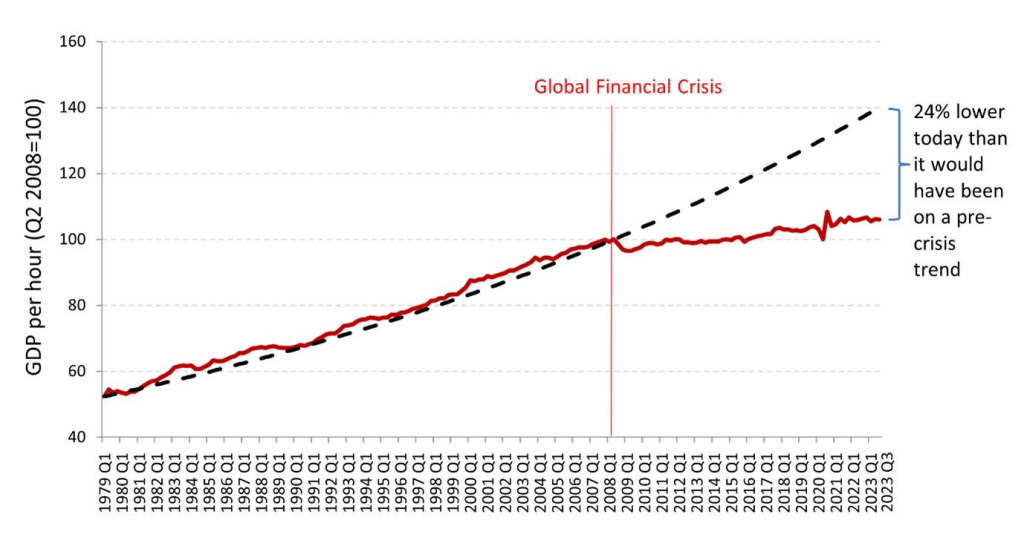

This period is known as a ‘Lost Decade’ where consumers living standards dropped and economic growth became stagnant. This stagnation of real household disposable income is significant as consumer spending is by far the largest driver of economic stimulus. Consumer spending represents 60% of the UK’s GDP (Source: ONS). Along with a flatline in real household disposable income came a drastic reduction in productivity. This was due to chronic underinvestment into new capital and skills by the private sector. By increasing productivity, economies can boost their capacity and produce more G&S for the same amount of work; this allows for higher wages and higher tax revenues for the government through the larger net corporate profits. This automatic fiscal policy that enables a positive feedback loop where governments reinvest into sectors within their economy unfortunately did not take place in the UK. The UK’s productivity is 24% below its pre-crisis trend, which is the second lowest productivity in the G7 (Source: ONS). See graph below (Source: The London School of Economics). UK productivity has stalled since 2008 due to low investment in technology, infrastructure, and skills. In 2013, only 6.1% of the government budget went towards investment into the economy (Source: UK Gov). Political uncertainty, including Brexit, has further dampened business investment, prolonging the slowdown.

Brexit was the first of the three major recent economic shockwaves, and its most significant impact was on direct foreign investment. Investment was reduced by almost 25% following the UK’s decision to leave the EU (Source: Bank of England). As reported by the Bank of England, ‘we estimate that more than 90% of this investment impact is associated with higher uncertainty’. Following Brexit, the COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated the underlying economic crisis that was brewing. The UK borrowed an additional £313 billion in 2020/21 representing 13% of its GDP (Source: House of Commons). This was deemed necessary to get the economy through the pandemic via policies such as the Furlough Scheme and the Coronavirus Job Retention Scheme. Those who were laid of from work were eligible to receive 80% of their original salary with a cap of £2,500 per month fully funded by the government (Source: UK Gov).

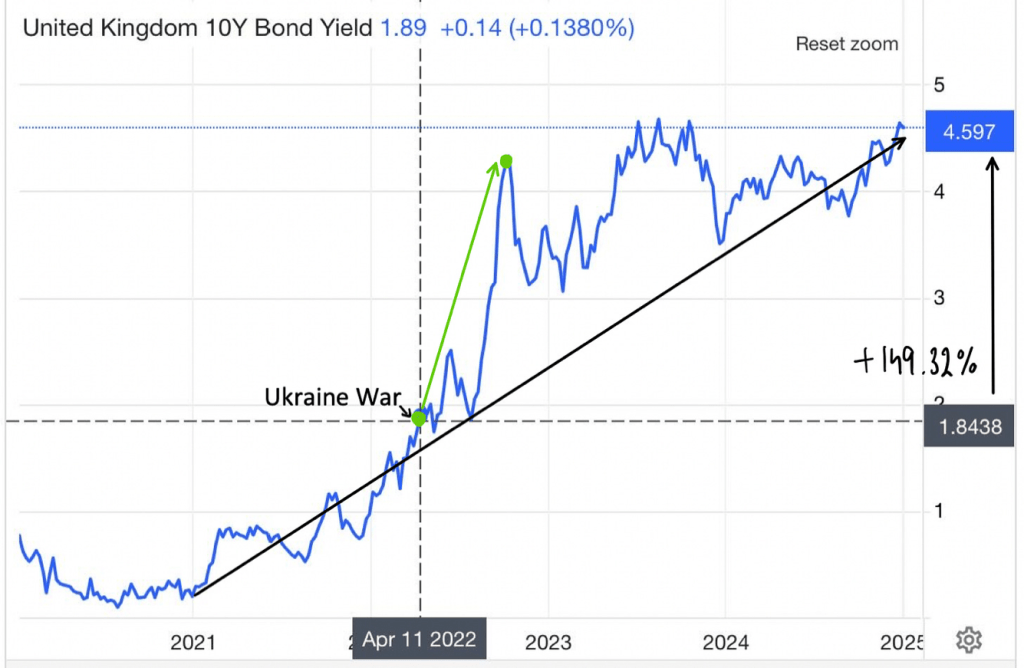

The surge in borrowing led to the soaring yields on the UK’s gilt bonds (Source: Trading Economics) and therefore cost to the UK government to service its debt. The UK private sector debt (households and businesses) is estimated at £2.8 trillion in 2023 or close to 110% of GDP compared to £2.6 trillion for the UK government debt which is around 100% of GDP. For sake of comparison, the German government debt in 2023 was €2.6 trillion which represents around 66% of Germany’s GDP at about €4 trillion whereas private sector debt is about €3.5 trillion of 87% of GDP. The difference between both governments debt levels expressed in percentage of their respective GDPs indicates that the UK government is 50% higher than Germany.

As UK debt soared, investor confidence within the debt capital markets dropped, leading to the prices of existing UK Gilts to fall in order for their coupons to represent a higher yield to match the yield level of newly issued Gilts. The graph above illustrates that yields on 10-year Gilt bonds since 2021 have increased from 0.3% to 4.6%, a 4.3% increase representing approx. a 15.0x fold increase. In comparison, the German 10-year bond yield increased by approx. 2.5% to 3.0% from negative territory to positive levels around 2 to 3% representing 1.5% lower cost compared to the UK Gilt yield. Subsequent borrowing, necessary to finance government spending (budget deficit of £127 billion in 2024) – (Source: Commons Library) depends on the market environment and expected inflation and is likely to remain in the 4.5% to 5% range.

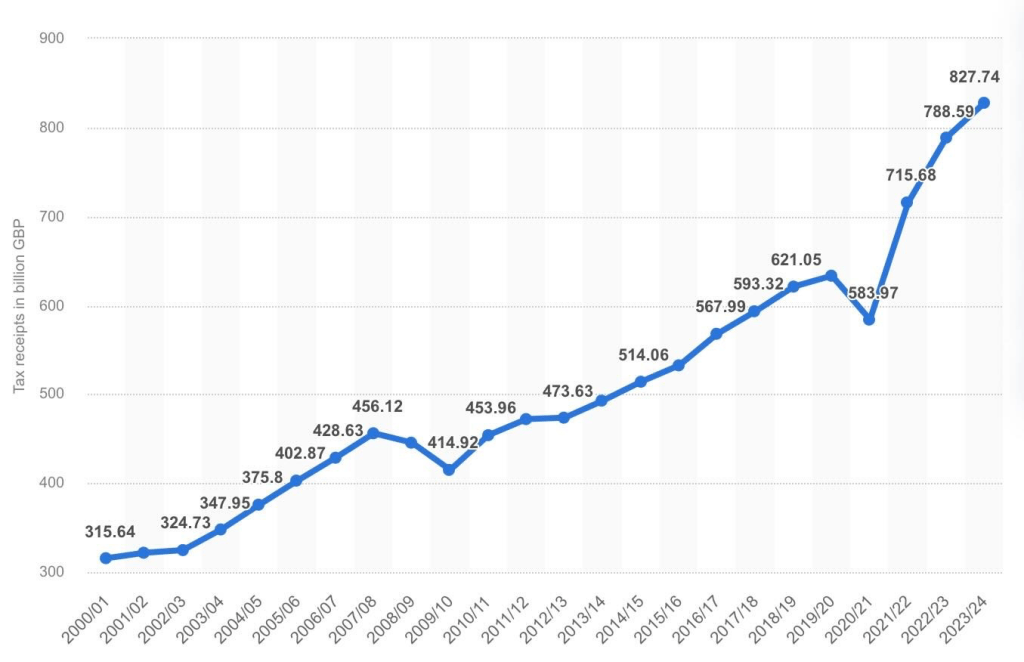

As the cost of financing debt increased during the 2023/24 period, 8.4% of government spending was on debt interest payments of £102 billion (Source: House of Commons) which led to increased revenue taxation in the UK to fund the interest payments on the UK government debt. See graph below (Source: Statista). Tax revenues recorded by HMRC reached £827.74 billion for the 2023/2024 tax year with only 5% spent on investment in the economy (public investments typically include infrastructure, R&D, education, and innovation). The UK government ability to spend on investment is being squeezed out by the increasing burden to fund public services and government interest payment with close to 67% being spent on public services (Source: IFS). As a result of this chronic underinvestment by the government in the UK economy, the UK will be struggling to re-emerge on the world stage. In comparison, the German government allocated 9% of its total budget to public investment in 2024 whereas the US and Chinese governments allocate 12.4% and 42.1% of their budget to public investments (Source: Centre on Budget and Policy Priorities).

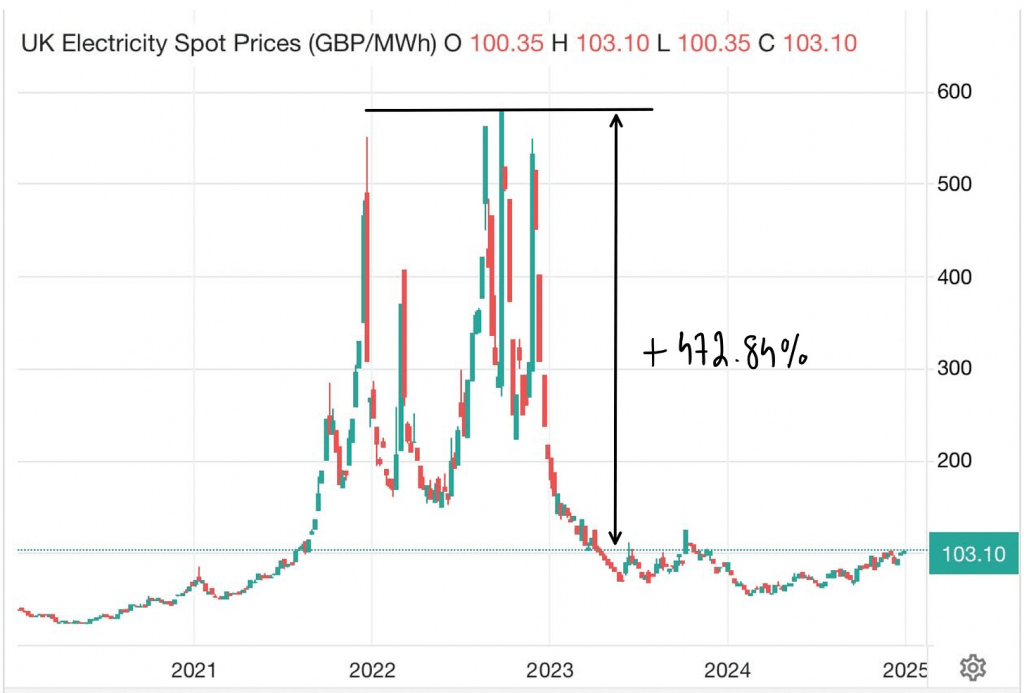

The war in Ukraine has exacerbated an already challenging economic environment. As Russia invaded Ukraine, £20 billion worth of trade with Russia (UK total trade activity with the outside world – including imports and exports – represented £1.5 trillion in 2021 including £20 billion with Russia or 1.33% of total) was sanctioned by the UK (Source: Official UK Gov). Energy prices reached record high numbers for UK households in September 2022, being close to 500% higher than previous prices of September 2021; see graph below (Source: Trading Economics). This led to high inflation and the cost of living for the ordinary UK household skyrocketed as a result. Inflation reached a peak of above 11% in October of 2022 (Source: Trading Economics), meaning that basic groceries and electricity utility bills became unaffordable overnight. In addition, as the Bank of England raised interest rates as a response to this surge in inflation, variable mortgage payments also quickly increased adding to the sudden cost of living crisis. Interest rates were raised from 0.75% at the start of the war to 5.25% by August in 2023 (Source: Trading Economics). The geopolitical instability caused by the Ukraine War startled investor confidence especially as Europe’s industrial competitiveness was heavily reliant on importing low-cost Russian gas. A full-scale war in Europe no longer seemed completely out of the question, and consequently, buying government debt was seen as ‘riskier’ and yields increased significantly by 150 (please refer to the green arrow on the 10-year gilt bond yield graph above).

To conclude, the UK economy faces a troubling trajectory marked by soaring debt, persistently high taxes, insufficient public investments and productivity, and stagnating household income. These factors have eroded the UK economy competitiveness and growth potential, casting a shadow over the UK’s economic prospects. With global uncertainties and domestic challenges compounding the strain, the outlook appears challenging to say the least. The UK economy is in need of decisive reforms to attract capital, foster innovation, and boost investment leading to increased efficiency and productivity. To stop its economic decline, the UK must implement a balanced strategy of fiscal discipline, including reducing public debt and investing in key sectors like infrastructure, green energy, and innovation. A key way in high government debt can be addressed is through a drastic reduction in government spending, however given the high tax rates already implemented; a further increase would likely be more detrimental, leading to lower disposable incomes for households and an increasing number of corporations relocating their operations abroad to hedge themselves against the surge in levy’s placed on them. Boosting productivity through labour market reforms, targeted skills development, and regional investment is essential, alongside fostering global trade relationships post-Brexit. However time is running out to reverse the downward spiral experienced over the last decades.