In the aftermath of the 2008 global financial crisis, Greece was faced with crippling debt. Resulting in the implementation of austerity measures (policies which reduce government spending and shrink the budget deficit), slumping GDP and overall political instability. Despite the UK being one of the largest economies in the world its national debt (£2,686 billion) has been ever rising, especially after the pandemic and specific inflation addressing policies, similar to that of Greece following 2008.

What Happened in Greece?

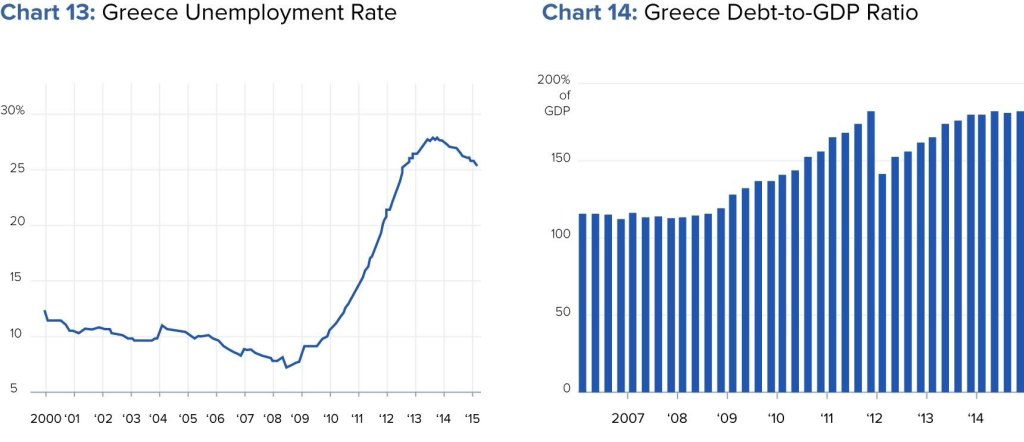

By 2010, Greece’s debt to GDP ratio 146.2% which made borrowing completely unsustainable. The main causes for this severe debt included the Greek government spending equating to approximately £81.5 billion (42.6% of GDP) while their tax revenue being £65.5 billion (34.5% of GDP). Tax revenue was below average due to the spike in tax evasion following the GFC, moreover Greece’s overreliance on external borrowing was exposed as a significant portion of its debt was held by foreign creditors. As a result, between 2010 and 2015 Greece received a total of three bailout packages, from the EU and IMF, of £244 billion, which further compounded their external debt obligations. Moreover, due to their instability the tourism sector experienced a downturn, with overnight tourist arrivals dropping by 6.4% year over year as the crisis began, affecting revenues in a key industry for Greece.

How does the UK compare to Greece?

The UK’s debt to GDP ratio is currently around 100%, mostly driven post pandemic spending and support measures during the energy crisis rather than chronic overspending and a lack of fiscal discipline. Unlike Greece the UK has a better record of fiscal transparency according to the International Monetary Fund and is seen as a safe borrower. However, rising public debt combined with higher interest rates has increased the cost of servicing this debt. This has prompted concerns about the true sustainability in the long run. Furthermore, despite the UK’s strong financial markets, growth has been sluggish in recent years due to low productivity and Brexit-related trade barriers. The OBR forecasts growth of around 1% annually. This weak economic growth could undermine the UK’s ability to reduce is debt over time. This is similar to that of Greece where the reduced public spending led to a 26% decline in GDP between 2008 and 2014 making it much harder to pay off their debt with their lower tax revenue, creating a vicious cycle.

Not only that, but both countries have responded with similar fiscal policies. To secure bailout funds, Greece imposed pension cuts, tax hikes and public sector layoffs as a part of there austerity measures. These policies furthered the recession and led to social unrest. This spiked unemployment to 27% in 2013, leading to increasing number of strikes and protests. While the UK has not imposed austerity measures on the same level as Greece, there have still been tax increases and spending cuts in the recent years. For instance, the UK implemented a windfall tax on energy companies and also raised corporation tax in order to respond to fiscal pressures. Counties such as Lebanon, Sri Lanka and Mozambique have similarly been experiencing rising debt, with Lebanon’s GDP to debt ratio exceeding 150%. All of these countries have weak or negative economic growth and poor structural reforms, characteristics that are somewhat similar to the UK.

While these are certainly similarities, the UK has experienced them to a far lesser extent than Greece has in the past. Yet, this does not make the UK completely immune to the possibility of an accelerated debt crisis like that of Greece.

Risks of a UK Debt Crisis

Recently the Bank of England has risen interest rates to combat inflation and continue to do so, meaning borrowing costs for the government have risen. The yield on a 10 year UK gilt has risen from under 1% in 2021 to around 7.9% as of recent. This is risky because this increases the government’s debt servicing costs, which were estimated at nearly £100 billion annually in 2024 which is more than the combined budgets of several key departments for example education and defence. If rates rise further, more and more government revenue will be used to repay interest instead of public services and investment. Comparing this to Greece, bond yields exceeded 35% during the peak of the crisis. While the UK’s situation is far less severe, any further increases in bond yields could strain public finances and diminish investor confidence.

Moreover, markets react very intensely to perceptions of fiscal mismanagement as seen in Greece. The UK’s 2022 mini-budget crisis is the most recent example where unfunded tax cuts caused bond yields to spike and the pound to depreciate. If investors lose confidence in the ability of the UK government to manage its debt sustainably borrowing costs could rise, leading to a loss of fiscal control. This would mimic Greece’s experience, where mistrust over the accuracy of its fiscal data caused a rapid sell off of Greek bonds. Not only that, but 30% of the Uk’s government debt is held by foreign investors. Despite this being quite a but lower than Greece’s dependency on external creditors any loss of confidence among these investors could lead to high capital outflow and a depreciation of the pound, making imports more expensive and boosting inflation.

Lessons from Greece to Avoid a Similar Story

The key lesson that the government should take from Greece’s experience would be to maintain fiscal discipline by ensuring that deficits are manageable and borrowing is directed towards productive investments rather than recurrent spending. Fortunately, the OBR (Office for Budget Responsibility) provides independent assessment of fiscal policy which is something that Greece lacked during its crisis.

Greece’s crisis was worsened by deep rooted structural issues, such as an overly large public sector, widespread tax evasion and over reliance on consumption driven growth. These ignored issues made reforms far more difficult than necessary. The UK, to avoid this, should boost investment in research and skills training to further productivity; and reduce inefficiencies in public sectors like healthcare and welfare programmes to lower longer term fiscal pressures. The UK should also continue to incentivise demand for gilts domestically like pension funds, while also maintaining the reputation as a safe investment destination for foreign creditors.

While the Uk and Greece do have fundamental differences in their economies and financial systems the UK is not far off Greece in terms of rising debt and weak growth. However, by learning from Greece the UK can mitigate the potential risks of a similar debt crisis. But with possible careless management, rising borrowing costs and external shocks, unexpected challenges could arise.