What strategies would be most effective for improving UK productivity?

Introduction

Enhancing productivity, defined as the ratio of output to input volume [1], is critical to unlocking higher UK economic growth. Productivity improvements account for half of the differences in GDP per capita across countries (Chart 1). Growth in labour, capital, and Total Factor [2] productivity would translate into higher standards of living and prosperity growth. As Krugman observed, “productivity isn’t everything, but in the long run it is almost everything.” [3]

In this essay, I first investigate the context and issues that have led to weak UK productivity before exploring opportunities to tackle this. Solving the UK’s productivity challenges involves addressing inter-related, long-term issues. I identify three strategies that would tackle root-causes of low productivity and transform the UK’s productivity.

Context and Challenges

Between 1997-2007, UK productivity growth was second only to that of the United States across the G7. Following the GFC, Brexit and Global Pandemic, UK productivity has been disproportionately hit (Chart 2). In fact, Britain’s GDP per head would have been £6,700 higher if its pre-GFC productivity growth rate had continued. [4] The UK’s problems run deep, and this led to stubbornly low productivity with a long-tail of laggard firms (Charts 3, 4). There are many reasons for this relating to the most basic forms of efficiency in the work place.

Labour productivity:

Labour productivity, measured by output per hour worked or output per job, has consistently been significantly higher in London and the South East compared to other regions, with this trend exemplified in the 2021 data. In London, output per hour worked was 33.2% above the UK average, and output per job was 41.4% higher than the national average. Conversely, the North East lagged behind, with output per hour worked falling 17.4% below the UK average in 2021, highlighting this significant regional disparities in productivity across the country. The UK has also experienced elevated levels of low productivity due to the effects on immigration, especially enhanced by the effects of Brexit, combined with long-term sickness has taken thousands out of the UK workforce (Chart 5). [5]

Capital productivity:

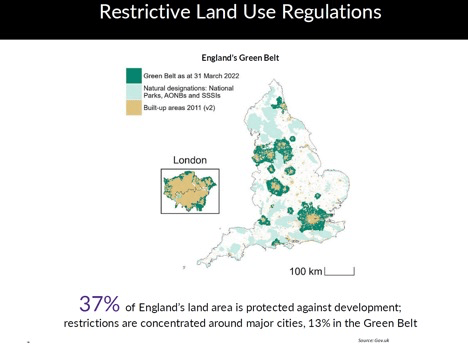

Capital productivity refers to the efficiency in which capital, such as machinery, equipment and infrastructure, is used to produce goods and services. This long-term business investment compared to competitor economies was further affected by Brexit and future international trading uncertainties. Long-term regional inequality and economic imbalances are also a productivity dead weight e.g., weakness in the North of England compared to the dynamism of London and the South-East. Planning restrictions also limit business growth, constraining high productivity firms from expanding due to lack of affordable housing [6] (Chart 6), limiting even the productivity growth of highly productive firms.

Sources of Hope

Despite these challenges, the UK possesses assets that can drive productivity growth. The UK is home to world-class, innovative firms, ranking top 5 in each of the past 5 years in the Global Innovative Index ahead of France and Germany. The top 1% of UK companies produced annual productivity growth of 8%, while the top 0.1% of UK firms delivered 12%. [7] This high performance is regional too; with the East Midlands’ top 0.1% of firms delivering 30% annual productivity growth. The UK is home to high-growth sectors such as Healthcare and BioTech that deliver world-class productivity. Top Transportation and Information firms have influenced the average productivity growth rates, between 30 – 40% p.a. (Table 1). This high performance must be magnified across all regions and sectors to ensure a highly productive future in the UK.

Setting the Conditions for Productivity Growth

UK macroeconomic stability is essential for fostering an environment for businesses to grow productivity. Uncertainty related to Brexit as well as economic policy and large-scale infrastructure projects has been unhelpful. Truss’ unfunded tax-cutting budget, Labour’s ditching of their £28bn p.a. green infrastructure plans, and the government’s HS2 retreat were detrimental, delaying critical infrastructure projects, and thus discouraging long-term business investment

Three Productivity Growth Strategies

Boost High Innovation Firms and Increase Commercialisation of Research Findings

The UK must leverage its research strength to drive commercial development. The UK does ‘R’ very well, as a world-leading innovation hub. However, it does ‘D’ poorly, which includes development plus the diffusion and dissemination of innovation to lower productivity firms. Three quarters of the UK’s private R&D spending comes from only 400 companies (< 0.01% of UK businesses). [8] Supporting high productivity sectors to commercialise their inventions is key.

Drive New Technology Adoption and Penetration

The UK needs to drive more widespread technological adoption and penetration, particularly at the dawn of the new AI revolution. [9] Economist Paul David has shown that technology revolutions only deliver significant productivity impact when they reach a 50% penetration rate (Chart 7). [10] As Solow noted in 1987,” the computer age was everywhere except for the productivity statistics” due to this level not being reached yet. Once computer penetration exceeded 50% in the US in the late 1990s, productivity growth reached 2.9% p.a. up from 1.4% p.a. in 1975-95. If the UK can dramatically reduce the time for Generative AI tools to transform business and labour practices, it will capture a larger share of the 1.2 trillion value (in Euros) being created via this new technology. [11] Initiatives such as the UK AI Forum will help to accelerate this by promoting collaboration between industries, enabling the sharing of best practices and knowledge, whilst also addressing skill gaps and data challenges, enabling organisations to integrate AI more effectively.

Improve Productivity of ‘Long Tail’ Firms

The UK needs to establish a ‘diffusion infrastructure’ mechanism to enable business best practices and knowledge to be transmitted from higher performance upper tail [12] leaders to lower tail laggards. Given 99% of UK companies deliver only 1% average growth p.a., the opportunity for improvement is significant. [13] As Haldane notes, “when it comes to innovation, the UK is a hub without spokes”, emphasising this lack of necessary connections or supporting elements to function effectively [14] First, supply chains can transmit best practices as ‘a natural infrastructure that could be harnessed can easily spread good practice across companies’ and so we can maximise this opportunity by utilising supply chains to improve these connection. [15] Secondly, the UK’s university network can improve technology transfer due to its research heavy qualities, and so we can take advantage of this by balancing this research with subsequent development with increased funding. Thirdly, an improvement in human capital management is needed as “ideas percolate through people”. [16] So we must place a greater emphasis on improving business educations for leaders, as their ideas and knowledge then trickle down, allowing this highly specialised education to flow through firms, maximising the chance of highly productive methods being adopted and taken advantage of by the greatest number of people.

Conclusion

At the dawn of the 4th technological revolution, the UK can establish a leading position in productivity growth by having the bottom three quartiles in the UK productivity distribution close the gap to the quartiles above boosting productivity levels by 13%, subsequently closing the gap to the US and Germany and boosting GDP by £270 billion. [17] By implementing these strategies I have proposed, the UK can bring sustainable long-term productivity growth, ultimately driving improvements in living standards and economic stability, regaining its leadership position in the global economic landscape.

Appendix

Chart 1

UK productivity, real wages, and GDP per head

Chart 2

Chart 3

UK, Germany, and France firm-level productivity (data for 2013)

Chart 4

Productivity in UK, US, Germany and France

Chart 5

Cumulative change in number of people aged 16 to 64 years inactive owing to long-term sickness, seasonally adjusted, UK, January to March 2017 to June to August 2022

Source: Office for National Statistics – Labour Force Survey

Chart 6

UK Building Regulations

Source: Gov.uk

Chart 7

Adoption rates of basic ICT technologies

Sources:

ONS Research Databases and Bank calculations. Notes: Basic ICT technologies refer to computers, internet, websites, e-purchases, and e-sales.

Table 1

Growth in the firm-level productivity distribution (aggregate, by region and by sector)

[1] OECD Compendium of productivity indicators (2023)

[2] Defined as a measure of overall efficiency with which capital and labour are used

[3] Krugman (1997)

[4] LSE Programme on Innovation and Diffusion (POID)

[5] UK Census (2022)

[6] A recent OCED land use governance index rated Britan second only to Latvia (18 countries surveyed) in terms of the difficulty of achieving permission for new building construction. Also, Cambridge is struggling to deliver even 50,000 new houses by 2040 due to lack of water infrastructure (Source: Financial Times, 24/25 February 2024). 37% of England’s land area is protected against development (Source: Gov.uk)

[7] Haldane (2018)

[8] Ibid

[9] Penetration is defined as the extent to which adopted technology subsequently reshapes processes and products in a company or country. Economist, Solving the Paradox (2000)

[10] Ibid

[11] Public First (2023)

[12] Ibid

[13] Ibid

[14] Ibid

[15] Ibid

[16] Ibid

[17] In 2018 prices. Ibid

Bibliography

Australian Government Productivity Commission (2023), 5-year Productivity Inquiry: Advancing Prosperity

CIMA (2022), Tackling the UK productivity puzzle

Drucker, P (1997), The Age of Diminished Expectations

Economist (2000), Solving the Paradox

Economist (2022), Low economic growth is a slow-burning crisis for Britain

Haldane, A G (2018), The UK’s Productivity Problem: Hub No Spokes, Academy of Social Sciences Annual Lecture, London

Hunt, J (2023), Jeremy Hunt’s four-pillar plan to boost productivity

LSE (2023), Chronic under-investment has led to productivity slowdown in the UK

McKinsey Global Institute (2023), What is Productivity?

OCED (2023), Compendium of productivity indicators

Public First (2023), Views on AI from Europe’s Businesses

The Productivity Institute (2023), The Productivity Agenda

Great stuff!

LikeLike