Introduction:

In classical economics, individuals are assumed to be rational decision-makers. Rationality in this case means making choices that result in an optimal level of benefit or utility to the individual making the choice. This view, which is known as ‘homo economicus’, or the economic man, is the portrayal of humans as agents who are consistently rational and narrowly self-interested, and who pursue their ‘subjectively defined ends optimally.’ However, rationality in economics often doesn’t align with rationality in practice. The classical model, including the modelling within game theory, assumes perfect information, unlimited cognitive processing ability, and preferences that are driven by rationality alone. Yet, in reality, human decision-making is often constrained by ‘bounded rationality,’ a term used by Herbert Simon to describe how individuals make decisions under information gaps and cognitive limitations.

In recent decades, behavioural economics has become an influential driver in challenging these traditional assumptions, showing that individuals often deviate from rational behaviour due to cognitive biases and emotion, therefore not acting with perfect rationality. People often rely on these mental shortcuts and succumb to bias, exhibiting loss aversion (meaning that they are more sensitive to losses than equivalent gains). Additionally, social and environmental factors heavily influence decision-making and often distort rational behaviour, contradicting the traditional assumption of perfectly rational behaviour by individuals.

Nudge Theory:

‘Nudges,’ exemplified by the simplicity of the term, are small actions that leverage irrationality and use it to guide individuals toward better choices. A nudge, therefore, is a subtle change in the way choices are presented, labelled by Cass Sunstein and Richard Thaler as ‘choice architecture’—“influencing decisions whilst preserving freedom of choice.” However, unlike government regulations and financial incentives, nudges work by taking advantage of psychological tendencies, such as default bias, the powerful ‘social norm,’ and framing effects or advertisement, to encourage beneficial behaviours in areas including sustainability, finance, and health.

The economists Richard Thaler and Cass Sunstein popularised ‘nudge theory’ in their book Nudge and illustrated examples of how policymakers and businesses can use small interventions to produce changes in human behaviour at efficient costs. The use of nudges, although a relatively modern idea, has grown to have an impact in organ donation policies, retirement savings plans, public policy, finance, and corporate management.

Real-World Applications of The Nudge and Their Impact

The default option is largely renowned as the most effective type of behavioural nudge. Think about installing new software on your computer: we mostly go with the ‘default’ or the ‘recommended’ settings. This ‘default option’ may be the way forward to boost organ donation percentages. Ana Manzano, in her paper on nudges, highlights that when this policy was implemented in Texas between 1994-1996, organ donation rates increased from 3% to 20% in just two years. The ‘default option’ nudge has proved extremely powerful by capitalising on the principle of inertia, which is the tendency of humans to stick with a recommended or already chosen option or setting.

The social nudge, often it is part of human nature to want to be part of a group or socially acceptable standards. This instinct can be beneficially manipulated in the world of tax compliance: Informing individuals about the majority of people in their community paying taxes on time taps into the social normative influence. This nudge encourages tax compliance by highlighting that fulfilling tax obligations is a widely accepted and expected behaviour.

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, are health nudges: The most well-known health nudge is no doubt the smoking warnings. I’m sure you have all noticed that on your dad’s or grandfather’s pack of cigarettes, there is often a graphic image displaying the possibly tragic effects of smoking. These graphic warnings on cigarette packages utilise both visual cues and loss aversion. The images prompt smokers to visualise the potential negative consequences of their habit, creating a powerful deterrent and nudging them toward considering the health risks associated with smoking.

The Ethics of Nudging: Nudging VS Sludging

As behavioural nudges have gained popularity the concept of a “sludge” or “sludging” has also grown in popularity. A Sludge refers to an intervention that increases friction and makes beneficial behaviours more difficult to achieve. For example, firms may use sludge-type tactics to make cancelling subscriptions difficult or to trap consumers in a blur of terms and conditions. Whilst nudges aim to help individuals make better choices, the sludge manipulates the same cognitive biases for profit thus creating an ethical dilemma of whether nudges should be used.

Behavioural Nudges in Public Policy

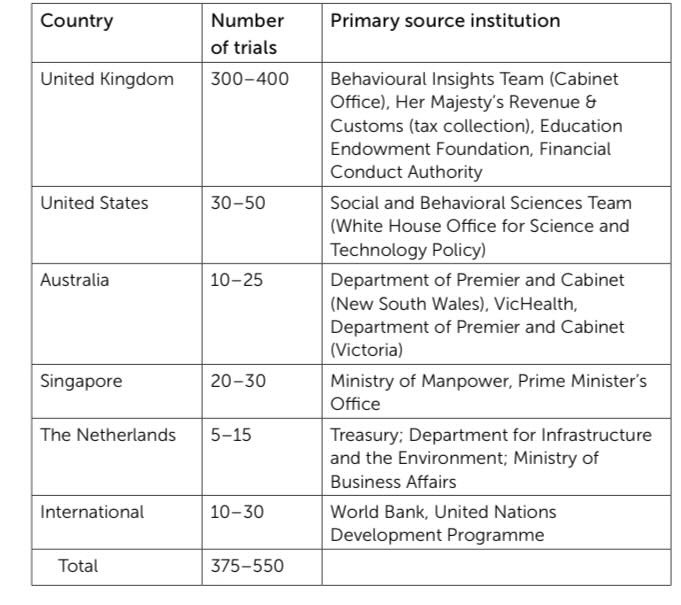

Table 1 shows examples of the United Kingdom’s behaviourally based interventions and their reach.

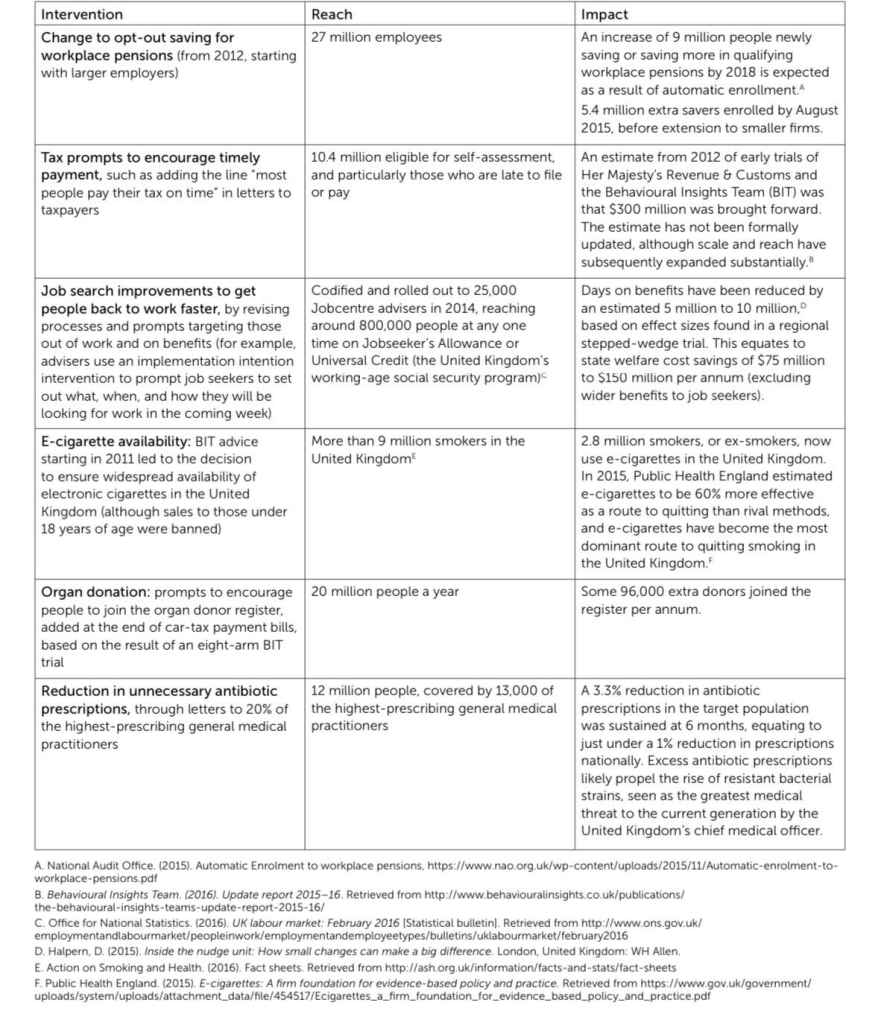

Table 2 shows the estimated number of trials conducted by behavioural units in government.

Additionally, nudges were an important part of Obama’s presidency, and he appointed Cass Sunstein himself as the Administrator of the Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs in 2009, where he was credited for institutionalizing behavioural economics in U.S governance and paving the way for the establishment of the Social and Behavioural Science Team (SBST) in 2015, whose idea was to use nudges to improve the effectiveness of policy without restricting freedom of choice. Sunstein also worked on green nudges and energy efficiency, supporting policies that encouraged energy conservation using behavioural insights, such as the use of home energy reports comparing an individual’s energy to their neighbours’ – capitalising on the social nudge. Despite Sunstein’s work in implementing nudges within policy, he was criticized for ‘soft paternalism’, with more liberal groups arguing that nudging was manipulative of individual autonomy.

Behavioural Nudges in Financial Markets

Nudges have even extended themselves into the realm of financial markets, where they are used to combat overconfidence and ‘loss aversion.’ The nudge was tested on online traders and displayed a ‘cool off’ message after a series of trades that occurred in quick succession. The nudge reduced ‘impulsive trading by 12%,’ showing the big impact of such a small action.

Moreover, nudges are now helping individuals manage their debt. For example in a trial, the UK’s Money Advice Service sent personalised text messages to individuals struggling with credit card debt. These nudges, which included suggestions for how to reduce spending and pay off debt faster, led to a 28% increase in the number of people making payments above the minimum amount.

Nudge theory has also been adopted in the business world, where it helps with management and improving corporate culture. It is commonly used in ‘Human Resource software’ and Tim Marsh believes that the nudge theory can help organisations ‘increase their safety and create a robust, zero harm culture.’ A lot of Silicon Valley companies are using various kinds of nudges to increase both the productivity and the happiness of their employees. ‘Nudge Management’ has even become a popular term, aiming to improve the productivity of white-collar workers.

The Future of Nudging: Beyond Behavioural Economics

As it stands, the future of nudges and behavioural economics seems extremely promising. Nudges are being used more and more on digital platforms which are all for personalised and detailed interventions. An example of this is that there now have been apps that can monitor consumer spending habits and can use nudges to help allow users to stick to their budgets and not stray away from long-term economic and saving goals.

Most crucially for the future, the use of nudges is beginning to prove effective in the areas of sustainability and environmental awareness. For example, nudges could encourage people to reduce their carbon footprints or recycle more often, potentially having larger impacts with the development of technology and the accumulation of research into human psychology.

However, as nudging becomes more sophisticated and persuasive, the ethical considerations surrounding its use will become increasingly complex, and balancing the potential benefits with concerns about privacy and autonomy will be a crucial challenge for both policymakers and ethicists in the coming years. As we harness this powerful, yet strangely simple tool, we must remain vigilant, says NeuroLaunch: ‘The line between influence and manipulation can be thin, and the potential for misuse is real.’ So, as we navigate the new world of behavioural science, it is crucial to remember that the most powerful nudge of all might just be knowledge itself.

One thought on “Nudges – A Dive into Behavioural Economics”