Thomas Malthus introduces his theory of population growth, which examines the relationship between the size of a population and the sustenance available to support growth, in his work An Essay on the Principle of Population. Specifically, it posits that population growth can be modelled by a geometric progression and food supply growth by an arithmetic progression. In other words, assuming the abundance of food is beyond what Malthus called the level of subsistence – the minimum standard of living necessary to support reproduction – and the finite area of land free for agricultural means, the population and food supply grow exponentially and linearly respectively.

The compounding nature of population growth may be explained by various factors. Most apparently, reproduction increases the size of the population. As the number of offspring rises, they themselves reproduce, leading to multiplicative growth. An individual is not limited to only one offspring, of course. In the presence of food abundance and high living standards (society is above subsistence level), the perceived prosperity incentivises more frequent reproductions: fertility rises along with high life expectancy and low mortality rate.

Alternatively, such a phenomenon can be deduced from a mathematical derivation. If we represent the population size as a function of time P(t), we can infer the future population P(t+Δt) is equal to the sum of the population at time t and the net increase – the difference between the number of births and deaths where b and d are average per capita birth and death rate respectively – which had occurred during the time period Δt as shown in equation (1.1). As a corollary, we get the discrete growth model (1.2) upon rearranging. Taking the limit of very small intervals of time as Δt tends to 0, we can see that the left-hand side of (1.3) resembles the definition of a derivative from first principles. Collectively, (1.3) is the continuous Malthusian growth model in the form of a differential equation. By solving the differential equation (1.4-5), we conclude with the conjectured exponential relationship (1.6) where P0is the original population.

As shown in Figure 1.1, given an arbitrary starting point in history, society has a food surplus when the population curve is below that of food supply due to sluggish preliminary growth. Over time, as the population surpasses the subsistence level bounded by agricultural supply, the living standard falls to such an extent that the society arrives at a Malthusian Trap: the exhaustion of food supply engenders war and famine. In these dire circumstances, where society balances finely yet precariously at subsistence, it is defenceless against negative endogenous shocks. Handfuls of case studies hitherto the Industrial Revolution can be called upon to illustrate the Malthusian trap.

During the Medieval Warm Period, which bridged the 10th and 13th centuries, Europe underwent drastic expansions in population. The warmer temperatures and prolonged growing seasons optimised crop-growing conditions, and the changing climate allowed farmers to benefit from the expansion of farmlands because high-altitude regions such as the Scandinavian countries became arable. This surge in food production ensured a sustainable food supply despite occasional inconsistencies in harvest yield. Harvest yield ratios c the amount of seed generated from every one seed – ranged from 7:1 to 2:1. However, a downturn ensued as Europe experienced the Great Famine, caused by worsening weather conditions at the crescent of the 13th century. Falling temperatures prevented the ripening of grains and persistent heavy rainfall led to flooding and difficulty in ploughing fields. The cost-push inflation engendered consequently from the supply shock made bread unaffordable for peasants who were entrusted with agriculture, who constituted 95% of the masses. Demoralised workers and inadequate nutriment led to a vicious cycle of food depletion. As a result, the population, stricken by starvation and disease, was reduced by 25%. This was, of course, aggravated by the bubonic plague pandemic, which followed forthwith and exacerbated the death toll by an additional 50 million.

As we can see, the ideal proposed by Malthus suggests a proclivity for population increase to be constrained by the food supply, preventing it from growing evermore. By virtue of the population-suppressing consequences induced as society approaches the Malthusian trap, collectively referred to by Malthus as “regressive checks”, they cause cyclical fluctuations around the level of subsistence (Figure 1.2). The basis of this behaviour is aforementioned. War, famine, and epidemics inevitably reduce the population manyfold. The falling number of people relative to the means of subsistence alleviates pressure and competition over these resources and per capita allocations increase. The shortage of labour in the market shifts bargaining power preferentially to the labour union, resulting in higher wages and a higher standard of living. The temporary abatement of financial pressure incentivises unrestricted reproduction. This, coupled with extended life expectancy and low mortality rate, drives up the population until it reaches the original subsistence level. Figure 2 illustrates this with the trend of wages against the population in the UK between the 1290s and 1610s. As can be seen, the overall holistic trend outlines an inverse linear relationship that conforms to the Malthusian conjecture, despite the graph taking the wage-population relationship as a random walk on an incremental short-term scale; after one fluctuation, wage and population in the 1610s closely match that in the 1290s.

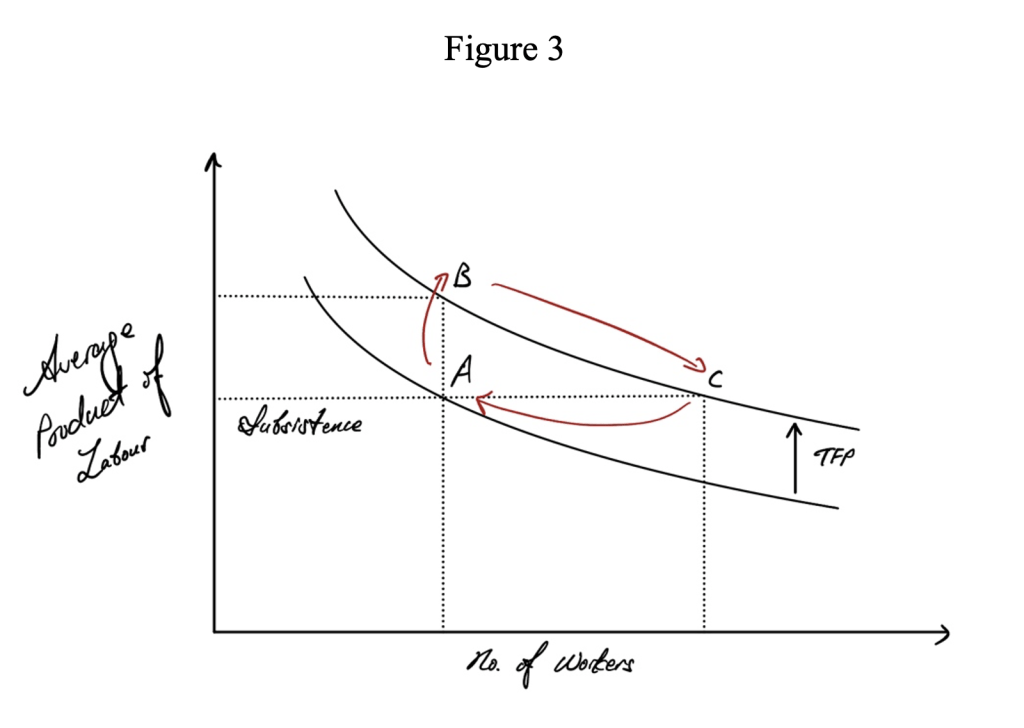

In entertaining the perhaps more pertinent case of technological advancement, which enhances productivity, we find ourselves again returning to equilibrium through the boom and bust of population. An increase in productivity – specifically, Total Factor Productivity (hereinafter TFP) – increases output per unit input. In an agrarian setting, a rise in TFP increases crop yield with the number of workers constant. In other words, TFP increases the per capita crop yields. Workers are rewarded with higher incomes. The rise in food yield and the consequent rise in income realise a Pareto improvement for all citizens; everyone is made better off, and the standard of living improves. The population thus rises by the mechanism previously addressed. Yet, when we implement more workers in the preexisting finite plot of land, per capita output falls back to the subsistence level due to the diminishing average product of labour: subsistence income is restored via the transition dynamic A-B-C (and at last A) following a TFP-induced shift in the average product of labour shown in Figure 3.

Irrefutably, Malthus’s theory of population is conceptually pessimistic, be it that population collapse inevitably follows fleeting periods of plenty or that the perishing of many is the cure – positive checks – to restore equilibrium; the pursuit of societal and economic prosperity in the long run is Sisyphean. However, is it at all feasible to push the boulder out of the Malthusian Trap? Well, Malthusianism struggles to stand the test of time. Though his conception was highly plausible during his time before the Industrial Revolution, it is anachronistic when viewed through a modern lens. This is so because of the technological advancements in agriculture and medicine which broke the assumed trends of Malthus. It is for this reason that Malthusianism is heavily excoriated by a coalition of economic and political dogmas. For example, Ester Boserup, an adversary of Malthus, rejected the idea that food was the limiting factor and argued instead that – according to her Boserupian growth – agricultural intensification and productivity increased due to mounting pressure engendered by the growth in numbers. By a similar channel, Friedrich Engels gave the reasoning that in a capitalist society, “progress is as unlimited and at least as rapid as that of population”. This was elaborated by Karl Marx that growth in population as a whole and also “relative surplus population” – that is, the unemployed and underemployed in an economy – is proportional to capital accumulation.

While Malthusianism may be defunct in developed societies, our conflict-ridden world is not too dissimilar from the societal nadir Malthus warned us about. Indeed, various countries still struggle with the consequences of the Malthusian trap: resources are to fight for, and food is to labour for. These localities are not absent from the casualties inflicted by the omnipresence of starvation and war. To fully ensure that these struggles are a worry of the past, we ought to collectively ensure the equality of innovation and development in all countries and provide a helping hand to those left behind; though needs are met in pursuit of our own interests, maximum return is realised when we also serve the interests of others.