Why is the NHS in crisis, and can it be saved?

For 75 years, the NHS has been a shining light for free at the point of service to use, universal healthcare. But, now, the National Health Service – a treasure of the United Kingdom – is in crisis. Waiting lists are up, A&E times are up, and its budget is ballooning. This has not been helped by strikes or COVID either. These factors all beg the question – where did it all go wrong, and can it still be saved?

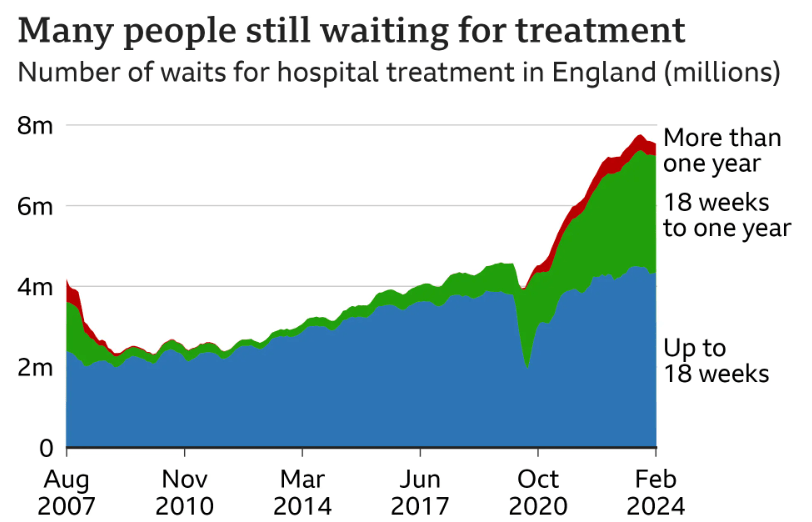

Figure 1: Source: NHS England, data to February 2024.

To understand why the NHS is not delivering currently, it is important to first understand why it worked in the first place. The Beveridge report in 1942 argued for the implementation of social policy, including an institution that delivers on the belief that access to health is a human right, and in 1948, the Labour government created the NHS, to provide free, universally accessible state-funded healthcare. The NHS uses the Beveridge model, meaning that a portion of general taxation is used to fund it. Rather than an individual paying, the whole of society buys in to ensure everybody has access to the NHS. This also means that the NHS could focus on delivering healthcare, rather than making profits, making treatment better. So what went wrong?

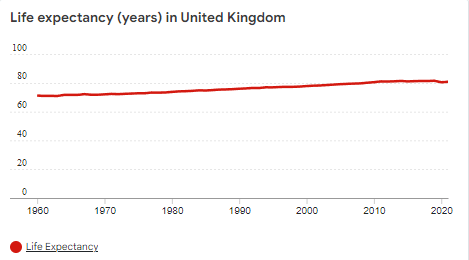

The first thing people might argue is that the world is different from 1948. Universal health care no longer works. People are living longer. Britain’s population is increasing in both number and age. This argument on first inspection seems valid, but the NHS has had to deal with these problems for decades, yet it could handle these changes. The fertility rate in the UK has remained fairly constant since the 1980’s (Figure 2), and the life expectancy hasn’t grown for the last decade, and before that, had been growing at a constant rate for the last 50 years (Figure 3). Immigration has been proven to add more to the NHS than it takes out. Further, the argument that the NHS costs too much is arguably untrue. The UK spends around five and a half thousand dollars per person per year on healthcare – lower than France and Germany, and half of what America spends.

Figure 2: Source: datacatalog.worldbank.org

Figure 3: Source: datacatalog.worldbank.org

There is another cause – a lack of plan to train doctors and medical professionals. A very simple concept that has been overlooked too much by successive governments is that it takes time to train doctors – some 14 years – by which time we may have different needs. The last government finally created a long term workforce plan – the first comprehensive one for two decades – but this is still not bulletproof to changing needs. The NHS in the past could rely on immigration to partially plug holes in the system (over 13% of the workforce in 2019 was foreign) but Brexit has caused this to become much more difficult, as the UK hugely reduces the free movement of people into the UK, especially Europeans, who made up 7% of the NHS workforce in 2019. Less skilled immigration has made shortages worse, all culminating in an estimated 150,000 vacancies in the NHS currently.

Then, there has been a gradual erosion of one of the very core ideas of the NHS – its nationalisation. Nationalisation has meant that competition is limited. Yet, in 1990, Margaret Thatcher made hospitals compete against each other for patients. 7 years later, Tony Blair made the NHS take expensive loans in order to build new hospitals. Then, in 2012 and 2022, David Cameron and Boris Johnson expanded the influence of private companies over the expenditure of NHS money. The government outsources healthcare to American companies using public money, and as a result, the NHS is being drained of its own doctors and nurses as private companies offer better wages, all while it was being weighed down by over 13 billion pounds of debt.

Each year, the NHS budget has to increase due to an increase in population and other, outside factors. It is currently at record high levels, but, thanks to the nature of natural economic growth and inflation, the real increase has been much more minimal year on year than it first seems. But, in 2010, David Cameron froze the NHS budget after the financial crash. This has cost the system a reported 50 billion for each of the last 14 years. It has caused doctors’ real wages to decrease 10%, causing the strikes we saw last year.

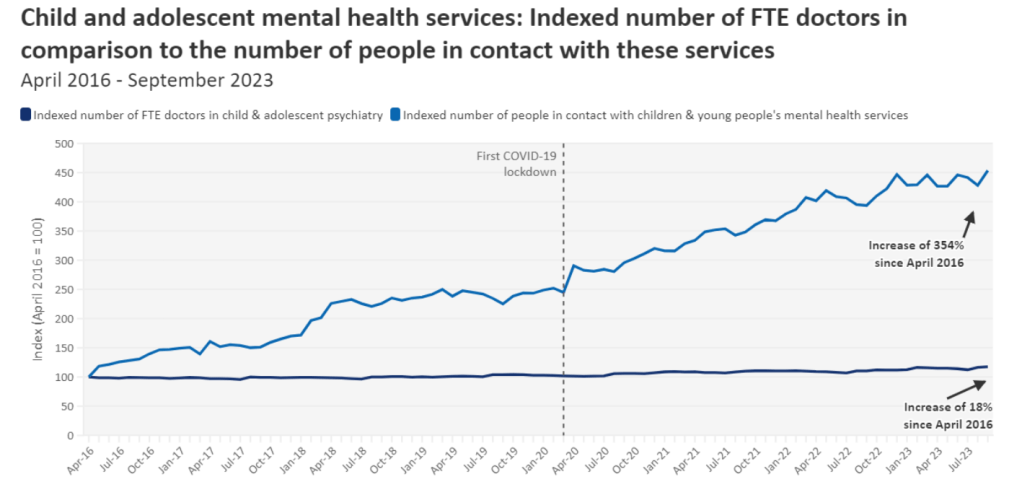

Finally, right on cue after nine years of underspending, COVID barraged the already exhausted NHS. A pause in ordinary practices – such as a normal health check-up – were cancelled, leading to a massive backlog that ballooned in numbers and is still being dealt with now. More than 6.5 million people are on a hospital waiting lists in England alone. The NHS in Wales is in utter shambles, whilst Scotland – despite avoiding a doctors and nurses strike – is still under immense pressure. It’s not only COVID causing recent headaches for the NHS. People seeking mental health support has increased 354% in the last 7 years, compared to a measly 18% increase in mental health specialists, putting further pressure on an overstretched and overworked NHS – reducing staff morale. Not only is mental health going up, but so is the rate of obesity: Britain has one of the highest rates of obesity in Europe. Obesity increases the risk of all sorts of diseases, increasing patients for the NHS. It all seems to be heading into a ‘death spiral’, with a bleak outlook for the future. But can anything be done to fix it?

Figure 4: Source: BMA analysis of NHS figures from April 2016 – July 2023.

Firstly, despite the belief by some that too much money is going towards the NHS, only 8.5% of GDP is being spent on healthcare. Though this is record spending, it seems manageable after considering that the USA spends 17.3% – more than double – on healthcare. Though it could be argued that the USA in general has more of a health crisis than the UK, it is still a vast gap. The NHS has been underfunded since the coalition government of 2010 to 2015, with the percentage of GDP being spent on the NHS actually dropping since 2010. How to fix this? It would not be financially prudent to try to recover the lost 650 billion pounds, but we can bridge that gap through focusing on efficiency, thereby combining efficiency gains with spenditure increases.

From increasing money spent, doctors could get pay increases, making it easier to retain staff who are moving abroad for better working conditions and pay, but also to attract foreign talent. This raises another solution – allow more doctors from foreign countries into the country to help plug gaps that arise in the NHS. Immigration will not fill 150,000 vacancies, but it can help in the short term, and allow more doctors in the future to gradually fill the gaps. For the doctors of the future, the government has to realise that the needs of the population are shifting. More consultants for mental health are needed, as well as other major health issues of the country, such as obesity and diabetes. It takes a decade and a half to train a doctor, meaning successive governments will have to continue to pledge to train more and more doctors.

The new Labour government has taken some steps, with waiting lists coming slightly down but still at record levels. It has pledged to hire 7,500 mental health practitioners, and have managed to stop the strikes and increase staff morale, though many feel that the inflation-busting rise is too much. It has pumped £25 billion more pounds into the NHS, but Labour has failed to set out any clear plan to increase efficiency.

To stop the obesity epidemic in its tracks, we shouldn’t focus on curing, we should focus on preventing it in the first place. The very causes of obesity and diabetes – for example fast-food chains such as McDonalds – could be made less appealing through increasing taxes on them, and then using that money raised to help solve the problem. Though obesity is going to be easier to prevent than mental health troubles, there are things that can be done to reduce the numbers of those suffering from poor mental health. One way is through building stronger communities. Many people struggling from mental health feel neglected and isolated, and bringing in more community areas may help this. The recent smoking ban that has been passed may help the NHS have to care less for diseases such as lung cancer caused by smoking, and though something like this would struggle to happen with fast food, restricting its availability or appeal would help reduce our obesity problem.

The last possible solution that could be implemented is the increase of hospital beds. Hospital beds have been cut and cut until now, Britain has only 2.6 beds per 1000 people, one of the lowest in Europe. Though one could argue this is thanks to the efficiency of the NHS, a patient can only be discharged from hospital so fast, and then cutting beds further could simply cause the system to be overwhelmed. Already, the NHS is consistently running at near- and sometimes over – full capacity. This has a knock-on effect. Ambulances are queuing outside for a bed, and even when inside, many are being forced to stay in corridors due to a lack of beds. Giving the NHS more beds, even if they are only being used 60% of the time, may help to greatly reduce the waiting times for ambulances and pressure on the system as a whole, despite its costs.

The NHS is in a bad way currently. After over a decade of underfunding, COVID, strikes, and Brexit, it’s functionality has been called into question. Yet, universal healthcare as a concept should not be treated as finished. We do not need to ‘strip down’ the NHS to providing only essential care. Instead, it can continue to serve its original purpose in the 21st century – providing care for anybody with any illness.