How a dual system distorted the economy

For decades, Cuban people lived with two different currencies in their pockets: the CUP (Cuban National Peso) and the CUC (Convertible Peso). However, it was not always this way. Following the collapse of the Soviet Union, the CUC was introduced in order to stabilise the economy—but at what cost? Whilst the implementation of the CUC helped stabilise the domestic economy in the short term, in the long term it distorted incentives, led to wage inequalities, and created a black market for foreign exchange.

Why did Cuba introduce the dual currency system?

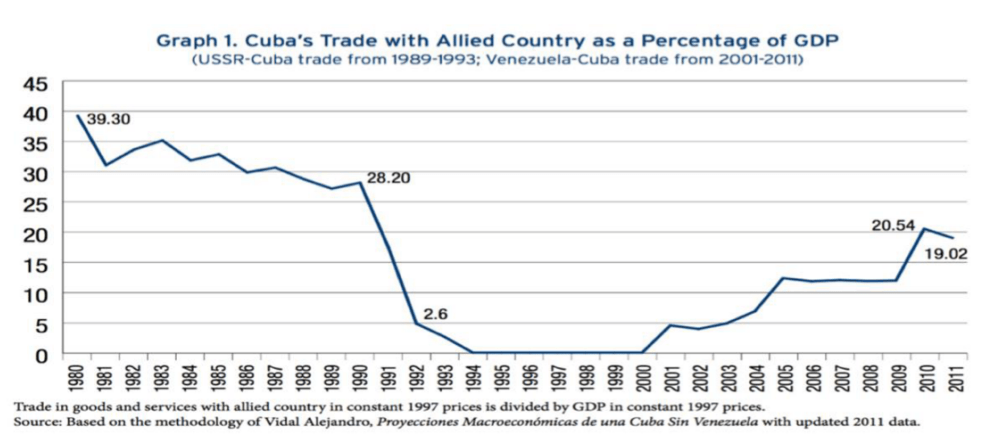

The dual currency system was arguably the only way out of Cuba’s financial crisis. Following the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, Cuba lost its biggest trading partner and financial supporter. Russia had supported Cuba with around 5 billion dollars annually. Overnight, Cuba lost 80% of its trade, leading to massive shortages of food, fuel, and consumer goods. With persistent shortages of essential goods, prices increased, leading to hyperinflation, which was only compounded by the government’s decision to print more money. Cuba needed a way to interact and trade with foreign countries, as the Cuban Peso (CUP) could not be exchanged directly for foreign currency. This is where the dual system comes in. Initially, in 1993, Cuba legalised the use of USD in shops but banned its use the following year due to confusion and a rise in black-market trading. In 1994, the CUC was introduced to protect the domestic currency and restore monetary stability in Cuba.

How did it work?

The CUP was fixed at a rate of 24:1 CUC, whilst the CUC was pegged to the US dollar. This system brought monetary stability and predictability to a precarious situation — but at a significant social cost. Moreover, the artificial exchange rate put in place by the government led to black market trading, as people knew the real value of the USD was far greater than 24 CUP.

How the dual system undermined socialism

The dual currency policy was problematic as it pitted the economic needs of the nation against its fundamental principles. The success of the dual currency policy led to social tension, as inequality rose, calling the country’s socialist ideals of equality in question.

Following the implementation of the policy, Cuba saw a large earnings gap between state employees earning wages in CUP and employees working in tourism and the foreign investment sector earning in CUC. This heavily distorted economic incentives, as highly skilled professionals like doctors and lawyers earned less than taxi drivers and hotel doormen. Remittances became a significant part of people’s incomes, which created a privileged class of Cubans with family abroad. The idea that a waiter at a hotel could earn a doctor’s monthly wage in tips is staggering. This disparity disincentivised people from working for the state sector, as it undervalued key workers’ importance and public service as a whole. However, on a broader scale, the social impact was the disparity and inequality that grew between classes in a country that revolted against these exact principles.

Furthermore, although some workers were paid in the national currency (CUP), essential goods were sold in CUC at global rates. For example, a bag of milk might cost around 2 CUC, about a week’s wages for someone earning an average of 800 CUP (roughly $30). The two currencies couldn’t coexist in a practical sense. The disparity between wages earned in the state sector paid in CUP and goods sold in CUC made life impossible for those who didn’t work in tourism or the foreign trade sector.

To illustrate this: In 2017, the official monthly salary was 767 CUP, equivalent to 28 CUC. Whilst this wage was enough for everyday purchases such as a cup of coffee (1 CUP), a bus journey (less than 1 CUP), and lunch (around 10 CUP), goods and services such as home repairs were hundreds of CUC, equivalent to several months of savings. The financial landscape that [rose out of] resulted from this policy incentivised people to rely on remittances, work that was paid in CUC, or informal work. The Cuban economy wasn’t utilising its potential and skilled workers were leaving key industries.

The rise of the black market

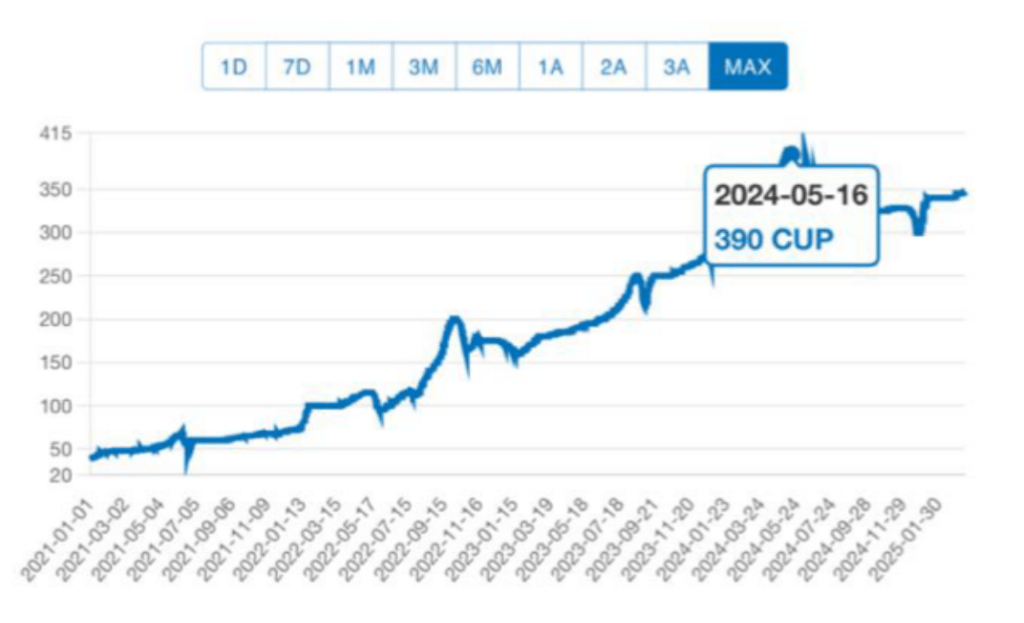

The dual currency system created a large black market for foreign exchange. The black market developed mainly because of the unrealistic value the government placed on CUP against the USD. People knew that the value of the CUP was far lower, so rather than trading the USD at government-run CADECA offices at the official rate, people preferred trading on the street at higher rates (i.e. 1 USD: 50 CUP). These illegal money changers were known as bolseros and were preferred by locals, tourists, and even businesses, further entrenching the black market in Cuba’s economy.

In the long term, this lack of incentives—especially for state sector workers—harmed productivity. Most other transactions took place in the informal market, which excluded government oversight and taxation. This inefficiency affected quality of life, as public services deteriorated, roads crumbled, buildings fell into disrepair, and access to essential goods became scarce.

A broken system: Weak fiscal balance and an economic decline

The dual currency system contributed to a weak fiscal balance. As people began to use the black-market system over the state-controlled system, the government lost out on tax revenue and foreign exchange earnings. The majority of transactions occurred off the books or illegally, meaning the official economy didn’t benefit from this growth. Further, the government had limited access to USD, as most dollars and foreign currencies were circulating the black market. These two effects meant that the government could not import essential goods such as medicine, food, and appliances. These shortages affected state sector workers and those without family abroad the most, as shortages grew and the purchasing power of their wages decreased. A cycle began to form in which shortages led to more black-market activity, which led to a weaker fiscal balance. This repeating cycle further magnified the inequality between classes in Cuba and the lack of incentive to work for the state sector.

Conclusion

What began as a temporary fix led to one of the biggest economic mistakes in Cuba’s history. The dual currency system widened inequality, disincentivised workers, and damaged the state. Despite good intentions, the policy pushed people into black markets and forced many into economic hardship. Whilst the two currencies were unified in 2021, its legacy still shapes Cuba today, as many of the struggles still remain.