When considering a country’s economy there are two types: emerging and developing. An emerging economy is characterised by transition in the economy of a nation from a pre-industrial, underdeveloped economic environment into an industrially competitive one which exhibits some, but not all, of the characteristics of a well-developed economy. The term ‘emerging market’ was first used by Antonie Van Agtmael of the International Finance corporation in 1981 as a marketing ploy to encourage investment in foreign economies from local investors but is now used as a general term for economies which exhibit high growth and signs of financial/industrial development. Some modern examples of emerging markets are Mexico and Turkey.

Emerging markets differ as they exhibit slightly different economic trends as they go through the process of industrialisation and have different potential for returns when investing compared to a developed market. Some signs that a market is ‘emerging’ are:

- An increase in market liquidity in the emerging economy’s stock market (given the country already has an established stock exchange) – liquidity is usually defined as a market’s ability to accept and accommodate large volumes of trades with little impact on price movements. This makes it an indication of both market breadth and resilience, giving investors more confidence in their investment as volatility reduces as the market develops.

- High levels of direct foreign investment – as a market develops, accessibility and publicity both grow simultaneously with the growth of industry. This typically attracts foreign investment both due to the low entrance prices and potential for high returns compared to developed markets which are typically made up of already well developed and established institutions. There are three types of direct foreign investment, each of which can impact an emerging economy in a different way. They are:

- Market Seeking FDI: Investment which comes when a market/company is predicted show highs levels of growth. There is often a high correlation between this type of foreign investment and GDP growth.

- Resource Seeking FDI: Investment due to a large amount of natural resources which have the potential to cause large amounts of economic growth either through selling them as a raw product or refining them.

- Efficiency Seeking FDI: When an economy offers services at a lower rate, typically in sectors like manufacturing, and therefore has the potential to experience an increase in foreign business as companies outsource labour internationally.

- The establishment of formal and modernised financial and regulatory institutions – i.e. practices seen mainly in developed markets around the world being adopted in the local market/economy – and the deregulation of restricted markets. Things such as the deregulation of capital markets (making entry to capital markets (e.g. stock and bond markets) easier to allow for more investment), the eliminations of price controls (legal maximum/minimum price of particular goods), and lowering trade barriers are all things which would fall under this neo-liberalistic approach often seen in emerging markets where many market-oriented reforms occur.

Why are emerging markets so popular?

As of January 2024, Emerging Markets made up 24% of the global market capitalisation even though they held 82% of the world’s population (meaning their economic footprint is much higher than their actual representation in financial market indexes which often omit them. For example, the MSCI failed to include China’s a-shares until 2018 and even now only allocates a small portion of their actual free float capitalisation in their indexes.); this alone suggests that these markets should see unprecedented growth compared to already well-established markets as their GDP increases and industrial production/capabilities catch up with the disproportional population they hold. Characteristics like high economic growth forecast and attractive valuations of companies often entice investors due to the high returns possible.

Additionally, Emerging Markets provide diversification to an investment portfolio in a way that developed markets do not. For example, if an international portfolio is particularly weighted towards US securities then if something were to occur causing a collapse in the US market (such as the 2008 crisis as an example), then said portfolio would suffer serious loses. This is where the concept of diversification comes in; while typically thought of as splitting a fund between various industries (allocating a quarter of capital to each of Pharmaceuticals, Tech, Real Estate and Communications as a simple example), if the assets held are all in the same market this makes the entire portfolio vulnerable to the same economic and geopolitical risks. Diversification across markets and geographical location can further increase a portfolio’s resilience as each individual asset is subjected to different risks and fluctuation due to this like political and legislative change.

There is an argument for the diversification of a portfolio to occur simply across developing economies as they are typically more stable and provide consistent returns. However, many of these developing economies are subject to the same risks and investing in an emerging economy can provide returns far higher than are seen in already developed markets.

Some things which are often seen in more successful emerging markets is a higher focus on research and development and a better environment for business, leading to the eventual rapid growth of the economy. A good example of this is the now developed economy of South Korea.

South Korea has shown very high levels of growth since the 1960s and is now stabilising to levels typically seen in developed economies. Some of the reasons for this growth are:

- Political Incentivization: by employing a model of export-led/focused industrialisation which encouraged companies to innovate and develop new technologies and be more efficient allowed the South Korean market to compete with international superpowers. This model allowed South Korea to become one of the leading world exporters with its GDP being 56.3% exports in 2012 compared to 25.9% in 1995.

- Environment and Approach: in 2018 the World Bank released the ‘world doing business rankings’ which can be seen below this bullet point. As is evident by the figures below, South Korea excelled in the ‘ease of doing business’ rank as well as the ‘starting a business’ rank when compared to the other economies listed. This would have greatly contributed to both the growth and subsequent stability seen in the South Korean economy as sectors diversified, returns were spread out across new industries and new institutions saw rapid growth.

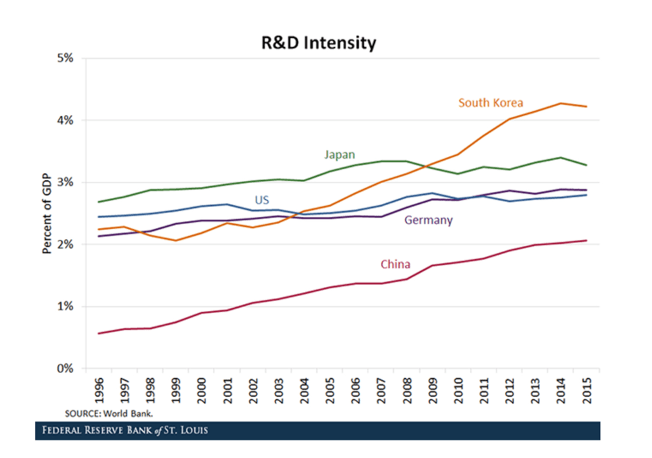

- Research and Development Focus: between 1996 and 2015 South Korea’s Research and Development intensity increased by 88.5% (from 2.24% in 1996 to 4.23 in 2015%) while other already developed economies lagged behind, as can be seen in the diagram below. This allowed South Korea to be competitive with other exporting superpowers as its advancement soared over its counterparts and greatly contributed to the economic growth seen in the country.

What are the risks that come with an emerging market?

As with any investment, investing in an Emerging Market comes with several risks. The most common error when investing in this kind of security is the wrong entry point. Entering a bull market (a market which has shown stable growth over a period of time) after several years of growth and stable earnings growth could yield one of two results: a continuation of stable growth or the topping out of a market, resulting in a flat or bear (opposition of a bull market) market in the years to come. In the short-term entry points can be even more difficult to get right due to the inherent volatility which comes with these markets, adding an additional layer of complexity. Finally, from an investors’ perspective, the promising outlook taken when discussing Emerging Markets can lead to said securities being overweighted in a portfolio without properly taking into account the volatile nature of these markets.

Stepping away from executionary risks, many Emerging Markets have downside potential that developed economies simply do not. Things like natural disasters or political instability (i.e. disaster risk) can create huge fluctuation in market stability and compromise returns on investments. Take Russia as an example, an economy which has been interchanging between a developed economy and an emerging market for the last 50 years. Coming out of a period of communism and poor economic policy created a huge amount of debt as foreign loans were used to finance domestic investments and fuel spending/consumption. This created the illusion of growth with GDP growth and share prices rising the Russian market gained popularity among those looking to invest in Emerging Markets. However, in 1998 when the Russian Government was eventually unable to repay said loans the government was forced to default its debts, leading to the devaluation of the Rouble and devastation to direct foreign investment in Russia as prices crashed.

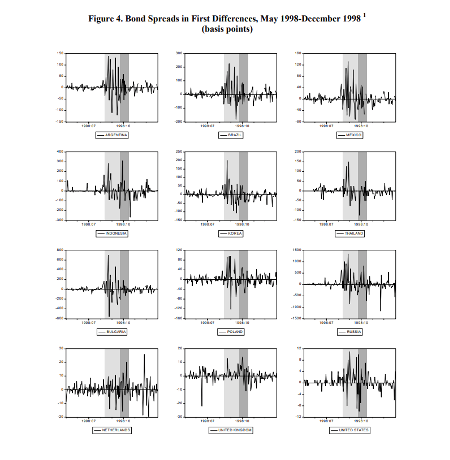

The crisis also had widespread effects on international markets. For example, the Sovereign default was a major factor in the eventual collapse of the LTCM (Long Term Capital Management) hedge fund and requiring a $3.6 billion bailout from the US Government. This singular event, partially caused by the Russian crisis, then had a spill over into almost all world markets (which had already been heavily impacted the Russian crisis itself) as bond markets experienced severe fluctuations as spreads changed, as can be seen in the diagram below.

However, while this devaluation would have been incredibly impactful investors already holding securities in the Russian economy as they rapidly depreciated it created an opportunity for new investment. Low company valuations provided a suitable entry point for investors; the devaluation also made Russian exports very attractive internationally which, alongside increased oil income, allowed the Russian economy to restabilise showing a 6.6% growth in 1999 and a 10% growth in 2000. This meant that any investors not scared away by the crisis in 1998 who saw the returns which could be made in the Russia as the country recovered would have benefitted immensely as a result of this stock devaluation, again showing how Emerging Markets can be utilised in an incredibly profitable manner if the correct steps and approaches are taken.

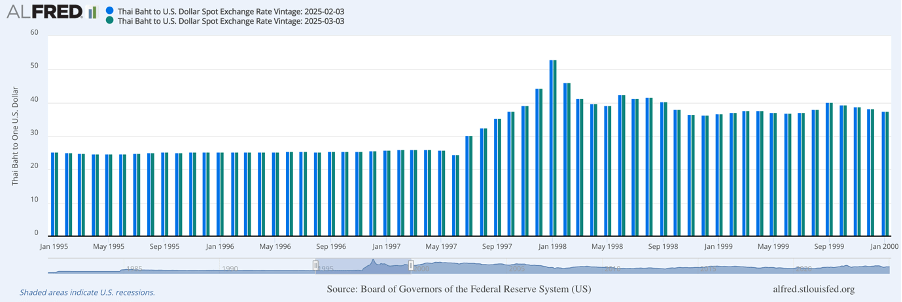

Another risk which comes with less developed economies is the risk of financial contagion, which is the idea that economic crises can spread between neighbouring economies and take hold across an entire region. A good example of the is the Asian financial crisis in 1997. In July 1997 when the Thai government ended the de facto currency peg of the Thai Baht to the dollar the currency saw huge devaluation, as can be seen below. This then lead to similar event in surrounding countries like Malaysia, the Philippines and Indonesia as their governments were forced to take similar actions – devastating investors in all economies affected by this crisis, not just in Thailand, which indicated just how volatile emerging markets can be and how changes which are not necessarily related to the economy can spread from other economies and lead to huge loses.

Economic Growth and Investment Returns

Typically, high levels of economic growth in a country are thought to bring positive investment returns to those who hold securities within said country’s market. This, however, is not always true. In 2014 the Credi-Suisse Investment yearbook, upon closer inspection, showed that there was cross-sectional correlation of –0.29% of real equity returns and per capita GDP growth for 21 countries with continuous data between 1900 and 2013. A similar study by J.R. Ritter looked at 15 Emerging Markets between 1988 and 2011 and again found a similar cross-sectional correlation of –0.41%. This tells us that strong economic growth in a country is not always correlated to positive stock market returns. Reasons for this may be that expected growth is already priced into listed securities or that the economic development in the country leads to more companies appearing and existing companies expanding, i.e. more shares are created and profit is spread out more widely, diluting the EPS value and impacting market pricing.

ETF’s:

A very common way of accessing emerging economies is through ETFs, or an exchange trade fund, which is a group of bonds, stocks and other securities grouped into a singular investment. Some prominent examples of these are the FTSE Emerging index and the MSCI Emerging Markets index. They allow easy access to the returns which can come from an emerging economy and reduce the need for portfolio diversification as they themselves are already suitably diversified for the markets on which they focus. This tends to be a better option than direct investment in securities in an Emerging Market as they can often contain several countries, again reducing the risk of a significant loss.

Why do Emerging Markets struggle to mature?

From 2009 to 2024 Emerging Markets have struggled to compete with their developed counterparts and have underperformed the developed sector (on aggregate). One reason for this is that emerging markets tend to be more sensitive to macroeconomic headwinds than developed markets. EM equity markets are often dominated by a singular sector, or at times even a singular company. This can lead to several issues. Firstly, if a sector were to become obsolete, rendered inefficient, become heavily taxed internationally or be subjected to a multitude of other potential issues the entire EM would suffer and even ETF’s tracking multiple markets could be negative timely impacted. Changes in leadership and conflict within individual institutions can lead to to severe devaluation across said institution: this would not be a problem if investment was diversified and the industry was made up from several major players but presents a huge issues if, as if often the case in emerging markets, the industry is dominated by one company alone.

More rarely, major global events can impact emerging markets in a way that developing markets are not. For example, during the covid-19 pandemic a country’s ability to recover from an economic standpoint partially relied on how quickly and efficiently its population could be vaccinated. This process would have taken less time in stable, developed economies which were better equipped to handle the medical needs of their populations with both better military organisation/efforts and a better trained medical community, meaning many developed markets would have greatly outperformed their emerging counterparts as they were able to return to pseudo-normality with less delay. To take the United States and Pakistan as examples, in Q4 of 2019 the US GDP was at $21,933 billion and was able to surpass this by Q4 of 2020 reaching $22,068 billion, recovering incredibly quickly from the pandemic. In Pakistan, GDP saw a continued decline in 2020, going from $320 billion in 2019 to $300 billion in 2020, only surpassing pre covid levels ($356 billion in 2018) in 2023 with GDP reaching $374 billion. The fact that it took Pakistan’s economy an extra two to three years to recover would have severely impacted investors in the area and subsequently meant that developed markets like the USA would have outperformed it, showing how global events tend to have a larger impact on emerging economies than on already developed ones.