Concorde. It dominated the skies for over a quarter of a century, and was the first, and for now, only, commercial supersonic jet. But in late 2003, still a technological marvel, Concorde left the sky for one last time. Even today, Concorde is put alongside the Apollo missions as one of the most technologically advanced projects this world has ever seen. Yet, despite halving the time between New York and London to only 3.5 hours, this so-called ‘time machine’ is now nothing more than a museum exhibit. So, what went wrong?

In 1962, supersonic transport (SST) was seen as the future of aviation. After a decade of astonishing advances, in an attempt to boost their own individual efforts, the French and British governments signed a treaty, in which they agreed to co-operatively build a supersonic commercial airplane. Given an original estimate of £160 million, the project soon blew way over its budget – by 1975, the year before Concorde took off, more than £1.2 billion (£11 billion today) had been spent. Still, both governments gave their full support for the project – fuelled at least in part by a clause in the original deal promising a huge financial penalty for any party that pulls out.

There was one major factor that led to the ballooning of the original budget – the sheer number of technological innovations necessary to make the plane fly. The plane was developed before the advent of computers, so engineers had to rely on trial and error to develop new parts of the plane. A completely novel ‘delta’ wing had to be designed, along with modifying military bomber engines to generate enough thrust to break through the sound barrier. Even though Concorde was designed to fly at 60,000 feet, the heat from air friction meant a whole new paint and bodywork had to be designed to make sure the whole thing didn’t melt. Then, after all the other physical changes such as designing a revolutionary new nose to allow the pilots to see the runway at landing, there were government spats across the Channel – work at one point was even halted due to an argument about whether to add an ’e’ to ‘concord’ or not.

However, Concorde faced further challenges before taking off. The Boeing-led American attempt at SST had been defunded after a supersonic test over Oklahoma City resulted in shattered windows and public outcry over the noise pollution caused by the sonic boom. This crushed the dream of a Los Angeles-New York supersonic route, and essentially made Boeing’s attempts defunct. This, amongst other regulation regarding the ozone layer, boxed the Concorde in, until it could only fly transatlantic. Though 74 Concordes were ordered, every single airline had cancelled them as a result of economic unviability. Even British Airways and Air France were reluctant to operate the aircraft, but were compelled to by their respective governments.

Despite these setbacks, in 1976, Concorde took flight. Though originally marketed as a faster way to travel, it soon had to pivot, as financial losses consistently mounted – by 1981, both BA and Air France had recorded net losses in the tens of millions. One of the main reasons it failed to appeal was the high prices of the tickets. This was caused by three main problems exclusive to the airplane.

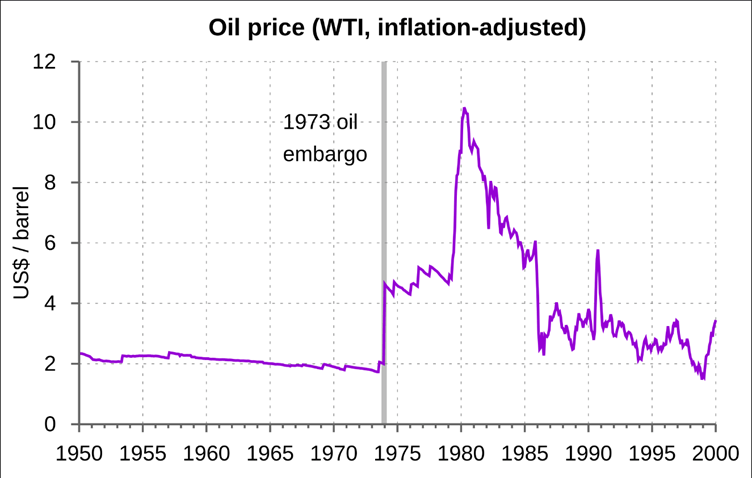

The first was fuel. Concorde was developed in the 1960s, when jet fuel was cheap. However, by the time Concorde hit the market, the 1973-74 oil crisis doubled fuel prices. This increase was manageable for subsonic planes, but Concorde’s engines were 4 times more thirsty than even first-generation jets, meaning any cost fluctuation would have a massive affect on ticket prices. The plane’s inefficiency was also the reason no transpacific route was ever created.

Figure 1: The price of oil adjusted for inflation at 1947 prices (West Texas Intermediate)

The second problem Concorde faced was its lack of capacity. The shape of the aircraft had to be long and thin to make it as aerodynamic as possible. However, this also reduced capacity. While a Boeing 777 – which is now used by BA on the New York-London route – can hold up to 350 passengers, Concorde could only hold at most 120. This meant that the cost of operations had to be spread across fewer passengers, driving up ticket prices to almost $12,000 for a round trip in 2003.

Maintenance and in-flight costs were also more expensive than for other aircraft types. A whole new maintenance system had to be introduced with a new plane, and the luxurious experience promised led to the retraining of stewardesses, and high-end catering. Additionally, at New York’s JFK airport, an extra Concorde was always kept on standby in case of mechanical issues on the ground, which meant it was not earning any revenue.

Despite these problems, by rebranding Concorde as a luxurious experience, British Airways bumped up the prices of tickets to over double that of first-class fares on a subsonic airliner. This managed to make Concorde profitable through the 80s and 90s. However, Concorde flights could no longer fill out all their seats. As a result, a chartering business began – for a large fee, you could get to fly supersonic to anywhere in the world for a once-in-a-lifetime experience. BA also started to sell vastly cheaper ‘supersonic experiences’, allowing those who couldn’t afford Concorde’s tickets a 1.5 hour experience on the aircraft. But Concorde’s resurgence would be stopped in its tracks after the turn of the millennium.

On July 25th 2000, Air France flight 4590 crashed into a field less than 2 minutes after take off from Paris. A stray piece of metal on the runway punctured a tyre, which sent debris into the fuel tanks, with the igniting a fire that caused the plane to lose control. Air France and British Airways grounded all Concordes, with a £17 million (£29 million today) safety improvement programme concluding with Concorde resuming service on November 7th 2001.

Unfortunately, the events of 9/11 just two months earlier meant the world had moved on. The airline industry had been depressed, and the number of businessmen flying into New York – Concorde’s main target – plummeted. Combined with the rising maintenance costs of a near 30 year old aircraft, Concorde failing to return to profit in 2003, and new, more fuel efficient planes sweeping the market, both British Airways and Air France decided to retire the plane for good. On October 24th 2003, Concorde left US soil for the last time, and touched down at Heathrow to end an era of supersonic travel. For the first time in the history of aviation, technology had gone backwards.

Perhaps Concorde was doomed from the beginning. 150 aircraft would have had to be sold for the development cost to be recovered, meaning that both governments lost huge sums of money in the name of innovation. Though BA claimed to have made £500 million of profit on Concorde, Air France only had very brief stints of profitability, and from 1990 onwards, had ‘only been operating for national pride’. A massive fleet of supersonic jets would likely have led to more environmental worry, but its high fuel burn and huge noise always meant Concorde could only fly certain routes. Along with enormous price tags, this made demand for Concorde persistently low. However, many others will argue Concorde might have lasted a few years longer without Flight 4590’s tragic crash and 9/11.

In the end, Concorde was an engineering triumph undone by the economic reality. A culmination of factors boxed the plane in tighter and tighter, until its only path was down, closing the only chapter (so far) of commercial supersonic transport. Now, all we are left with is a technological marvel left collecting dust as a museum artefact; such is the power of economics.

Great article – original, well reearched and written, and very interesting. Thank you. Bill Webb (dad of Eton alumnus Rob Webb – NPTL) and Camridge Economics scholar

LikeLike