Can Austerity 2.0 Bring Back Growth and Prosperity to the UK Economy?

Introduction

In October 2024, Chancellor Rachel Reeves announced a £40 billion tax increase, the largest since 1993, aiming to address the UK’s budget deficit and tackle the £22 billion ‘black hole’ from the Tories. Austerity refers to the policies aiming to reduce government deficits via spending cuts or tax hikes. Despite the Labour Government previously criticising the 2010-2016 austerity measures of the Cameron/Osborne administration, Reeves has now adopted a similar fiscal approach, causing outrage particularly over the NIC (National Insurance Contributions) tax hike, labelled by many as ‘Austerity 2.0’.

This essay examines whether ‘Austerity 2.0’ can rejuvenate the UK’s economic growth and prosperity, and argues that, although theoretically austerity could bring positive economic effects, the reality has and will be different. Most likely, our policies won’t find more success than those in 2010-2016.

Investor Confidence

High public debt erodes investor confidence. Sovereign credit ratings, which assess a country’s creditworthiness, decline as debt rises, raising borrowing costs. A lower rating raises borrowing costs, as investors demand higher yields to compensate for perceived risk. Hence, a vicious cycle occurs, with rising debt leading to higher interest payments and borrowing rates, exacerbating fiscal debt further.

The International Monetary Fund emphasises that higher debt-to-GDP ratios diminish investor confidence, necessitating higher risk premiums on government debt. Reinhart and Rogoff (2010) agree that exceeding 90% debt-to-GDP hampers growth[1]. In 2011, S&P downgraded the US’s long-term credit rating from AAA to AA+, primarily due to escalating national debt, underscoring the intricate link between a country’s fiscal health and market confidence. The Expansionary Fiscal Contraction (EFC) hypothesis posits that under certain conditions, fiscal consolidation bolsters private sector confidence. Counterintuitively, it proposes that austerity will lead to economic expansion in the future, anticipating lower future taxes. Alesina and Ardagna (2010) argue that EFC boosts investor confidence if markets believe spending cuts will increase long term growth[2]. One might expect, then, that austerity could increase investor confidence and economic development.

However, in December 2024, the UK’s national debt reached approximately £2.6 trillion (100% of GDP), its highest since the 1960s[3]. The impact of this is clear; post-October 2024, government borrowing costs increased, evidenced by rising gilt yields, indicating investors are demanding higher returns to offset perceived risks. The Business Confidence Index contracted significantly in Q4 2024, falling from 42 to 36[4]. This decline suggests that austerity measures may have dampened business sentiment, perhaps due to anticipated reductions in public spending.

Figure 1: UK gilt yields chart from 2008-2025, showing yields at an all time low of 0.162% on 9 March 2020, and a steep rise since COVID-19. As the gilt yields rise, it becomes more expensive for the UK government to borrow, as the new debt issuances come with higher interest rates. – (Sharing Pensions, 2024)[5]

Clearly, EFC hypothesis hasn’t applied here, due to the sluggish growth of 0.1% the UK experienced in the final quarter of 2024[6]. This could be for multiple reasons: the increase in NIC tax has inadvertently escalated operational costs for businesses, and, instead of stabilising public finances, surveys indicate that 90% of employers anticipate higher employment costs, with 42% planning to raise prices[7]. Perhaps the austerity measures are not enough to kickstart the stagnant growth that the UK is experiencing, as the Bank of England has revised its growth forecast for 2025 downward to 0.75%, reflecting their concerns[8]. Guajardo, Leigh & Pescatori (2014) support the idea that austerity depresses demand, and challenges economic growth further[9]. Overall, whilst one may expect austerity to increase investor confidence, the effect has been the opposite, keeping UK growth stagnated.

Inflationary Management

Austerity is often advocated as a strategy to control inflationary pressures by decreasing public spending, and hence aggregate demand. Keynesian theory suggests spending cuts reduce demand-pull inflation[10].

In late 2023, the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) projected that inflation would decline to 2.2% in 2024, approaching the Bank of England’s 2% target[11]. This forecast was based on anticipated fiscal tightening, and a reduction in public sector borrowing (outlined in the OBR’s October 2024 Economic and Fiscal Outlook), from austerity.

Despite these expectations, inflation did not decrease as projected. In January 2025, inflation rose to 3.0%, surpassing the initial target[12]. This suggests that the influence of government spending and borrowing was significantly overpowered by other factors, such as rising energy prices due to geopolitical tensions, and wage demands from public sector unions, which counteracted the intended effects of austerity. Lombardi, Mohanty & Schrimpf (2018) argue that fiscal tightening has limited effectiveness in reducing inflation when cost-push factors are dominant, as in the UK[13]. The expected outcome of austerity on inflation has almost been reversed, and the policies have simply been dampened by external factors, causing inflationary pressures to still be an issue.

Growth and Productivity

Austerity measures can inadvertently suppress economic growth and productivity, not only through NIC tax increases, but through reduced government spending. Keynes’ Paradox of Thrift posits that if an entire economy attempts to simultaneously increase savings, for example through widespread spending cuts in austerity, the decreased aggregate demand caused may result in lower production, layoffs, and ultimately, decline in productivity[14].

Government cuts, such as cancelling the Advanced British Standard, restricting the Winter Fuel Payment, and halting unaffordable transport infrastructure schemes, are projected to save £8.1 billion in 2025, to address the £21.9 billion shortfall in public finances (the ‘black hole’)[15].

However, this austerity has had a significant impact on productivity. As well as the BCI decreases, 5,547 companies ceased operations from October-December 2024, marking the largest quarterly increase in closures since COVID-19[16]. Small businesses are suffering, with approximately 13,479 retail stores closing in 2024[17]. Keynes (1936) described how uncertainty leads firms to delay spending, causing stagnated growth and the decline in private-sector confidence[18]. Baumol’s Cost Disease explains how industries that rely heavily on human labour are struggling disproportionately too, since austerity cut public investment[19].

Figure 2: A graph representing Baumol’s Cost Disease. Services that require human labour are disproportionately struggling, with prices rising the most due to public investment cuts from austerity. Due to the heavy reliance on human labour, which cannot be easily automated or made more efficient over time, these industries cannot lower costs easily with efficiency improvements. Van Reenen (2018) shows that cutting spending in these sectors hence limits long-term economic potential[20]. – Sourced from Full Stack Economics via Slate (Smith, 2022)

This impact should be entirely expected from the budget cuts, however. Resource constraints mean essential resources are limited, and lower government expenditure on infrastructure and innovation stifles long-term economic growth. Decreased aggregate demand could be a significant factor in the economic stagnation we see. Cuts such as the cancellation of road and railway schemes are projected to save £785 million, however they also reduce transport efficiency, and hence could sacrifice potential productivity[21]. For consumers, Ricardian Equivalence suggests that rational consumers anticipate future tax cuts following spending reductions, however empirical studies (e.g. DeLong & Summers, 2012) find that, in practice, heightened uncertainty leads often to precautionary savings[22].

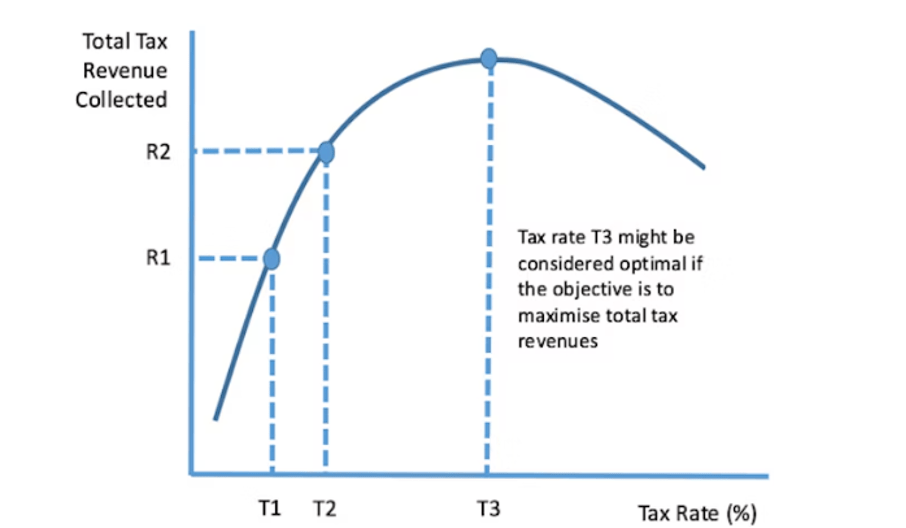

When considering the NIC tax hike, Tax Incidence Theory explains how employers, employees, and consumers are suffering. Businesses face higher labour costs, so employees deal with lower wages, and consumers tackle higher prices. OECD tax elasticity studies find that payroll tax hikes discourage hiring, weakening the labour market[23]. A survey by the CIPD revealed that 25% of UK employers plan to reduce their workforce before the tax hikes take effect in April[24]. The UK has perhaps reached a point on the Laffer curve where overall revenue is lower than before austerity[25]. Essentially, both the increased taxes and decreased expenditure has meant businesses and productivity have suffered, creating the opposite intended effect and limiting growth.

Figure 3: The Laffer Curve here suggests that, while raising tax rates increases revenue initially, at a certain point, higher taxes discourage work, investment, and hiring – leading to lower overall revenue. – (Tutor2u, 2024).

Conclusion

Austerity 2.0 is unlikely to deliver significant growth and prosperity. Despite expected benefits, such as increased investor confidence and inflationary management, austerity has actually exacerbated several economic challenges. Hence, austerity has not led to economic growth, as productivity and growth have become stagnant, business confidence is drastically decreasing, and inflationary pressures are still prominent.

[1] Reinhart, C. M., & Rogoff, K. S. (2010). Growth in a Time of Debt. American Economic Review, 100(2), 573-578.

[2] Alesina, A., & Ardagna, S. (2010). Large Changes in Fiscal Policy: Taxes versus Spending. Tax Policy and the Economy, 24(1), 35-68.

[3] Office for National Statistics (ONS). (2024). Public sector finances, UK: December 2024.

[4] Savanta (2024). Business confidence decreases in Q4 2024. Retrieved from https://savanta.com/knowledge-centre/press/business-confidence-increases-in-q4-2024/

[5] Sharing Pensions. (2024). UK Gilt Yields Chart 2008-2025.

[6] Office for National Statistics (ONS), 2024. GDP first quarterly estimate, UK: October to December 2024.

[7] Reuters (2025). UK firms brace for hit from tax hikes, surveys show. Retrieved from https://www.reuters.com/world/uk/uk-firms-brace-hit-tax-hikes-surveys-show-2025-02-17/

[8] Reuters (2025). Bank of England cuts rates, sees higher inflation and weaker growth. Retrieved fromhttps://www.reuters.com/world/uk/bank-england-cuts-rates-sees-higher-inflation-weaker-growth-2025-02-06/

[9] Guajardo, J., Leigh, D., & Pescatori, A. (2014). Expansionary Austerity: New International Evidence. Journal of Development Economics, 112, 41-63.

[10] Keynes, J. M. (1936). The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money. Macmillan.

[11] Office for Budget Responsibility. (2024). Economic and fiscal outlook – October 2024. Retrieved from https://obr.uk/economic-and-fiscal-outlooks/

[12] Office for National Statistics (ONS), 2025. Consumer price inflation, UK: January 2025.

[13] Lombardi, M., Mohanty, M. S., & Schrimpf, A. (2018). The real effects of debt. BIS Quarterly Review, March 2018.

[14] Keynes, J. M. (1936). The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money. Macmillan.

[15] Reuters, 2024. New UK finance minister to accuse last government of multi-billion pound cover-up. Available at: https://www.reuters.com/world/uk/new-uk-finance-minister-accuse-last-government-multi-billion-pound-cover-up-2024-07-28/

[16] UK Government, 2024. Company insolvencies: October 2024.

[17] The Guardian, 2025. UK lost 37 shops a day in 2024, data suggests.

[18] Keynes, J. M. (1936). The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money. Macmillan.

[19] Baumol, W. J., & Bowen, W. G. (1966). Performing Arts: The Economic Dilemma. Twentieth Century Fund.

[20] Van Reenen, J. (2018). Increasing Productivity in the UK. The Economic Journal, 128(610), F1-F47.

[21] UK Government, 2024. Chancellor: I will take the difficult decisions to restore economic stability.

[22] DeLong, J. B., & Summers, L. H. (2012). Fiscal Policy in a Depressed Economy. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, 2012(1), 233-297.

[23] OECD (2024). Taxation and Employment: Labour Market Effects of Payroll Taxes. Paris: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.

[24] CIPD (2024). Labour Market Outlook: The Impact of Tax Changes on UK Employment. London: Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development.

[25] Laffer, A. B. (2004). The Laffer Curve: Past, Present, and Future. Heritage Foundation.