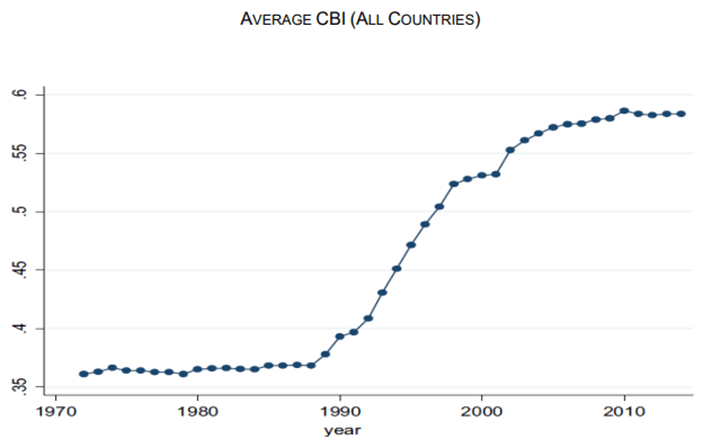

When the Bank of England was finally granted independence by the new Labour government in 1997, the Economist ran the headline, ‘Free at last’. This move belatedly joined a rapidly growing trend worldwide of governments granting central banks independence. By the end of the 20th century, central bank independence (CBI) had risen to around 80-90% (Chart 1), while the independence of these banks had also increased significantly (Chart 2), becoming a globally accepted truth of economics. Yet, CBI has come under increasing pressure in recent years, driven partly by a rise of populist and nationalist politicians. This increase in attacks have put the concept of an independent central bank back into the spotlight.

Chart 1: Percentage of independent central banks. Source: Garriga (2016) using the independence index of Cukierman et al. (1992).

Chart 2: The average CBI across all countries. Source: De Haan et al (2018), using the independence index of Cukierman et al. (1992).

The late 20th century boom in truly independent central banks is largely attributed to the inflationary periods of the 1970s. Many saw the interference of politicians leading to central banks – even supposedly ‘independent’ ones like the Fed – allowing the inflationary episodes of that decade to occur. This led to the creation of mandates, such as inflation targets, that allowed central banks to pursue these independently, better insulating them from political interference. It also provides credibility for the central bank’s policy actions, increasing financial stability. These two concepts have been cornerstones of the independent central bank post-2008 – managing price control whilst safeguarding financial stability.

The Time Inconsistency Theory by Kydland and Prescott (1977) provides a sound reason for political interference in monetary policy. This theory states that a policymaker’s preference currently will be different to a future preference. As a result, plans put forward for the future may be changed when the future arrives. If this does happen, credibility in the policymaker achieving its stated long-term goals is reduced. An erosion of credibility in monetary policy is particularly damaging, when much of it is based on expectations, which subsequently determines behaviour. If credibility is lacking, monetary policy becomes much less effective, as behaviour starts to influence policy, rather than vice-versa.

The chances of a time-inconsistent monetary policy is heightened with more political interference. Politicians tend to favour lower interest rates than independent central banks. As a result, central banks will be pressured to lower interest rates[1] by politicians in order to boost short-term economic output and increase the incumbent’s re-election chances. This is what happened in America during the 70s, when repeated rate cuts were designed to give a short-term output stimulus. However, as expectations adjusted, an inflationary bias emerged, where unemployment remained at its ‘neutral rate’ whilst inflation began to rapidly rise, leading to the economically-damaging stagflation seen during the late 70s.

Further, partisan political interests would likely lead to more time-inconsistent monetary policies. Political interests’ effect can still be seen in fiscal policy. Governments tend to cut taxes in the last year of government, often running large deficits that are popular, but unsustainable in the long term. It is very likely that a return to politicised monetary policy would lead to the same thing – interest rate cuts that are tempting due to short-term increases in output, but unsustainable in the long-term. This increases the chances of a time-inconsistent monetary policy further.

As a result, the consensus amongst economists is that political interference with monetary policy is negative. The delegation of monetary policy to a politically independent central bank has come to be accepted as a principle of good governance. This is supported by Binder (2020), which analyses the effect of political pressure on central banks and inflation. Both cases of when central banks resist and when central banks succumb are found to be associated with higher inflation, but with an even stronger relationship when the central bank succumbs.

Despite this, a rise in opposition towards central bank independence has still occurred –even with empirical data showing a clear negative correlation between inflation and central bank independence, whilst also not hurting growth. Beyond potential political gain, opponents cite other reasons.

The first is the lack of democratic oversight over an independent central bank. Central banks usually have a committee that votes on holding or changing interest rates. However, Forder (2002) and Friedman (1962) suggest that the anti-democratic nature of independence, due to these policymakers being appointed rather than elected, leads to more self-serving[2] and less accountability, having adverse effects on monetary policy. Further, a government’s popularity – and subsequent electoral fortunes[3] – is strongly affected by the state of the economy. This leads to governments taking the blame (or credit) for independent monetary policy and their subsequent effects. Giving the monetary policy mandate back to the government would allow for democratic representation in monetary policy[4], not only fiscal policy.

However, a counter-argument to this is the large swathes of empirical data (Alesina & Summers, 1993; Binder, 2020; Carlstrom & Fuerst, 2009, Klomp & De Haan, 2010 to name but a few), that suggests independence has a positive effect on monetary policy. Further, politicised monetary policy is unlikely to not be self-serving politically, in line with the Time Inconsistency Theory. Moreover, monetary policy is not alone in its common conflict between popular decisions and policymaker independence. Monetary policy by its nature requires a very long time horizon – not something that is very compatible with politics and the short-term demands of voters. Removing the insulation monetary policy has from public opinion risks the prioritisation of politically beneficial short-term gains at the expense of the future. In addition, central banks, like the Fed, are still held accountable to their congressional mandate..

Another argument detractors propose is that independence itself does not lead to ‘better’ monetary policy. Instead, central bank transparency is the key. The argument that Cargill (2016) presents cites the focus of measurement literature on de jure rather than de facto measures of independence. He uses the Bank of Japan as an example – until the 1990s, the BoJ produced better price stability than the Fed, whilst having one of the least de jure independence in the world.

However, in Cargill’s paper, he surrounds much of his case on the ‘Japan problem’, without addressing the overwhelming empirical data that supports central bank independence. Transparency is undeniably important in providing financial stability, but giving the government the monetary policy mandate gives no guarantee in increasing transparency – indeed, it may reduce it, due to hiding long-term costs, having less credibility in tackling price control and the continued increase in transparency that has been seen in independent central banks.

A third argument presented against CBI is a potential misalignment between fiscal and monetary policy. Central Bank Independence does naturally disable effective co-ordination of fiscal and monetary policy. Indeed, monetary policy is somewhat reactive to fiscal policy – the Fed has maintained rates due to uncertainty around the effect Trump’s tariffs. The return of monetary policy to the government would likely lead to better co-operation. The positives of this are especially apparent in crises – the disconnect between the European Central Bank’s loose monetary policy and the majority of the eurozone’s tight fiscal policy led to a suboptimal policy mix , with the ECB’s unwillingness to act as lender of last resort likely deepening the crisis . By combining both fiscal and monetary policy under the government, similar situations could be mitigated better.

Though this may be true, it is also possible to see the Time Inconsistency Theory play out here as well, leading to worse long-term outcomes. Further, the independence of central banks can act as a disciplinary check on fiscal policy, which would be lost without CBI. The performance of central banks during the financial crisis itself has also been plauded with avoiding a collapse of the financial system. In light of this, the potential misalignment between the two policies seems minor in comparison to the potential of unchecked fiscal policies along with politicised monetary policy.

Overall, the monetary policy mandate should not be given to the government. Much of the criticism of CBI have come from politicians looking to utilise monetary policy for political gain, consistent with the Time Inconsistency Theory. Empirical data shows a clear negative correlation between inflation and independence, and while critics may argue this is correlative rather than causative, the evidence is incredibly suggestive. Attacks of CBI being undemocratic also fail to address monetary policy’s inherent long-term focus, that would be compromised if returned to governments. As Kohn (2013) says, ‘there is just too much history behind the concern that less independence leads to higher inflation over time’. Until there are strong enough trends and data to suggest otherwise, monetary policy should remain in the hands of an independent central bank.

[1] Nixon is quoted as saying ‘I respect his independence. However, I hope that independently, [the new Fed Chair Arthur Burns) will conclude that my view are the ones that should be followed.’

[2] Money is too important to be left to the central bankers’. Poincaré, as quoted by Friedman (1962).

[3] ‘It’s the economy, stupid.’ James Carville, Clinton Strategist, 1992