Economic growth, most often measured by the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) growth rate, is the engine that propels nations from poverty to prosperity. It is the driving force behind rising living standards, the creation of new opportunities, and the expansion of human potential. Yet, the question remains as to how this varies between nations. Will the long-standing economic giants always be ahead or will less developed nations eventually catch up? This is the issue of economic convergence.

In 1956, neoclassical economist Robert Solow published a contribution to the theory of economic growth in the Quarterly Journal of Economics; meanwhile, Trevor Swan simultaneously developed a parallel theory, drawing the same conclusion. Their discoveries and propositions lay on the strong foundation of the Cobb-Douglas production function, shown below as:

• Y: Output (GDP)

• K: Capital

• N: Labour

• z: Total factor productivity (TFP)

• α: Capital share of output

Using this equation, Solow and Swan modelled capital accumulation over time in per capita

teams:

• s: Savings rate

• n: Population growth rate

• δ: Depreciation of capital

• f(k) = k^α: Output per worker, as a function of capital per worker

With this fundamental equation, which highlights the idea of diminishing returns to capital,

Solow and Swan put forward the theory that economies will eventually reach a point of zero

growth in capital per capita, and, despite shocks, they will always return to this steady state.

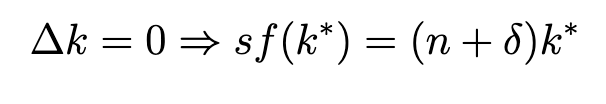

At the steady state (k^∗), capital per worker does not change:

Solving for steady-state capital per worker, k^∗, we obtain:

With this fundamental theory, the economists illustrated that any economy will always converge towards this equilibrium despite potential differences in economic variables. This is known as unconditional convergence and expresses the idea that developing economies will eventually reach the same economic level as developed nations, regardless of initial GDP per capita, and will reach this same steady-state equilibrium where investment exactly compensates for the depreciation of capital and population growth. However, empirical evidence shows that unconditional convergence is too strong an assumption, due to other macroeconomic variables that need to be controlled for beyond GDP; this gave rise to the notion of conditional convergence – the idea that each economy converges to its own steady state based on the economy’s specific characteristics. Thus, convergence is only observed after accounting for these underlying factors.

This study analyses data from 39 high income countries for the period 2012 to 2022 to investigate economic convergence as predicted by the Solow-Swan growth model. Countries were defined as high income countries based on the World Bank’s definition, which identifies countries with a Gross National Income (GNI) above $13,205 as high income countries.

The primary variable used for both unconditional and conditional convergence is real GDP per capita (PP, constant 2021 international $). The natural logarithm of this variable was taken and used as the x axis input during the regression analysis, represented as ln(y{i0}). The equation used to calculate GDP per capita growth over the analyzed decade is as follows:

After various regression analyses, and using economic intuition, the following variables were selected based on their significance, for the initial year 2012:

• Population growth (annual, %)

• Trade openness (trade as % of GDP)

• Government consumption (% of GDP)

• Finance (domestic credit to private sector as % of GDP)

• Urbanisation (% of population)

• Unemployment (% of population over 15)

We assessed both unconditional and conditional convergence using a simple regression analysis. Our baseline model for unconditional convergence is:

Where:

• α is the intercept

• β is the convergence coefficient

• ϵ is the error term

For conditional convergence, the baseline model is extended to include a variety of structural control variables, all measured at the initial year 2012:

Where X{i0} includes population growth, trade openness, government consumption, unemployment, urbanisation, and finance.

As established earlier, unconditional convergence is the idea that economies with a lower

initial GDP per capita will grow at a faster rate in per capita terms than economies with

a higher initial GDP per capita. This idea is rooted in the idea of diminishing returns to

capital, represented in the equation for the marginal returns to capital:

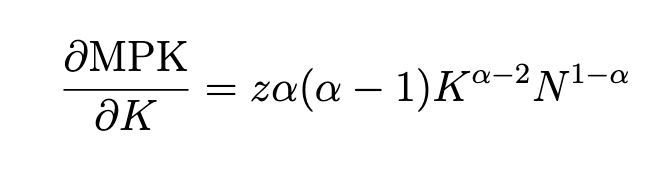

To show diminishing returns to capital, we differentiate MPK with respect to K:

Since 0 < α < 1, and (α − 1) < 0, the expression we get is negative which mathematically

shows that the marginal product of capital declines as capital increases.

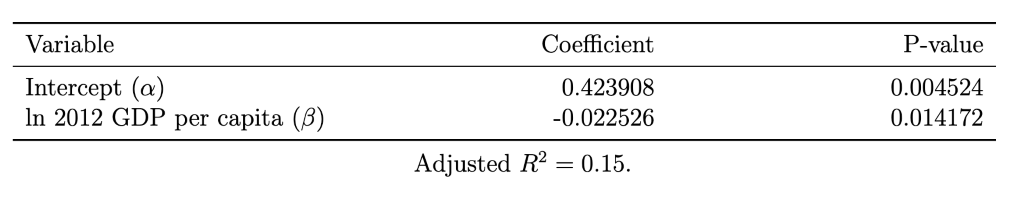

From our regression analysis testing for unconditional convergence in 39 high income countries, we found the following results:

A p-value smaller than 0.05 implies that the variable it corresponds to has a significant effect

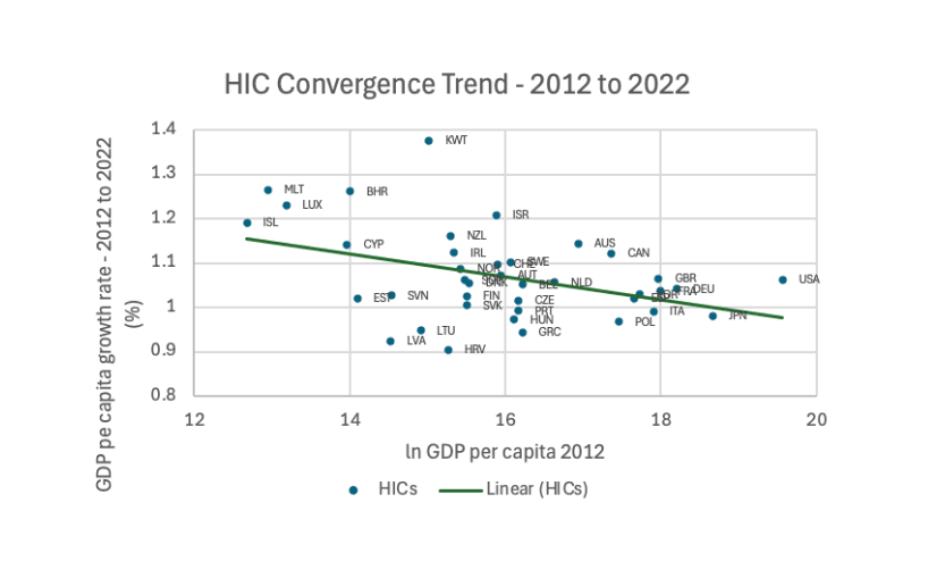

on the x axis variable. The negative convergence coefficient we found (β = −0.02256) implies that unconditional convergence was occurring in high income countries from 2012 to 2022. Considering that the variable was statistically significant (p = 0.014172), the reliability of this conclusion is reinforced. If we plot the convergence trend for high income countries

during this period, we find the following graph:

The negative trend line on the graph again reinforces the findings from the regression analysis, as it suggests that unconditional convergence was occurring, as, as the initial GDP per capita of a high income country increases, its per capita growth rate decreases.

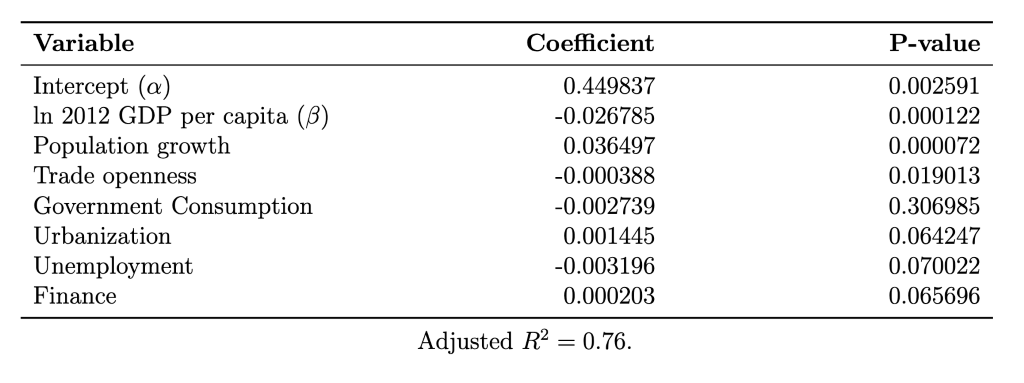

The regression analysis testing for conditional convergence in high income countries revealed the following results:

Again, the negative convergence coefficient (β = -0.026785), suggests that conditional convergence was occurring. This conclusion is again reinforced by the statistically significant p-value (0.000122). When accounting for all several variables, we see a clear increase in the explanatory power of the model, with the adjusted R^2 value, of 0.76, which implies that the selected variables account for 76% of variation in per capita growth rates seen in high income countries during the period. The model for unconditional convergence had an adjusted R^2 value of 0.15, meaning that the model accounting for other variables was a much better fit for the data, strengthening the hypothesis of conditional convergence.

The robustness of these two models was tested in several ways. For unconditional convergence, a residual plot was constructed, which revealed no obvious shapes or patterns, with the residuals being evenly scattered around the x axis, providing evidence that the model shows no signs of heteroskedasticity or nonlinearity.

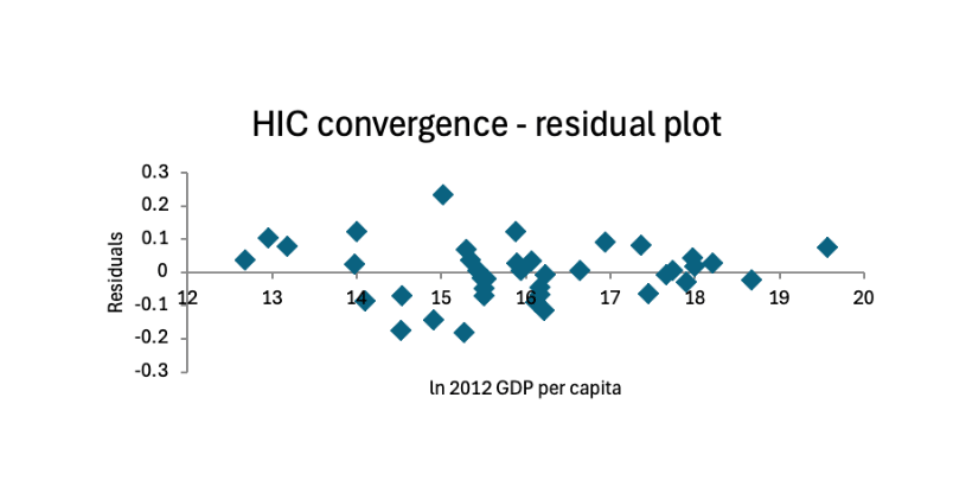

For conditional convergence, various tests were conducted. A correlation matrix, which involves analysing the correlation between different variables revealed no multicollinearity. Additionally, variance inflation factors which again test the correlation between variables were uniformly low, with the highest value found being 2.3, well below the recommended threshold of 5. The Breusch Pagan test revealed that the critical chi-squared value, a test statistic which indicates to what extent data deviates from the predictions of the null hypothesis, which states that the variance of the residuals in a model is constant across all observations, was greater than the Breusch-Pagan statistic, which measures whether the variance of the regression errors depend systematically on the independent variables. This means the model fails to reject the null hypothesis, providing evidence that there is no heteroskedasticity in the data.

Overall, the regressions testing for conditional and unconditional convergence as posited by the Solow-Swan growth model revealed that both conditional and unconditional convergence occurred from 2012 to 2022 in high income countries, and show the increasing in reliability of the hypothesis of conditional convergence when compared to the hypothesis of unconditional convergence, shown in the increase in explanatory power of the regression for conditional convergence when compared to the model for unconditional convergence.